Natural or Man-Made?

Falmouth is one of the world’s largest natural harbours and is steeped in history. A ‘natural harbour’ is one which is large and deep enough to give shelter to a collection of shipping. The harbour is natural because it is surrounded by land except for a relatively narrow entrance. If shipping is going to gather in quantity there needs to be a fairly easy entrance and a large area of deep water contained within.

Too difficult to get in risks a shipwreck blocking the entrance and frightens off shipmasters approaching for shelter in bad weather. Too shallow and there is not enough room to accommodate a fleet of ships. Poole Harbour is a good example of what is unsuitable. Virtually completely landlocked it has a very narrow and difficult entrance, which has to be dredged, and, once inside, there is little room for a large ship to anchor without touching bottom as the tide falls.

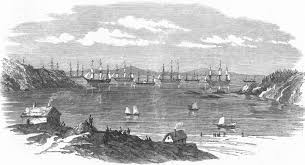

The need for a navy to find a large sheltered anchorage to accommodate a fleet gave rise to various places in the world where a breakwater has been built to provide extra shelter. Our nearest example is Plymouth where the land provides good shelter except on the southern side. Way back in 1690 the Admiralty decided that Plymouth would be the main naval base in the south of England. Why not Falmouth? Probably the distance from the Admiralty in London, bearing in mind the roads available at the time.

The journey could take five or six days – longer in winter. Anyway, Plymouth it was and for over a hundred years this was a base for the Home Fleet. But there was a problem – the Sound was completely unprotected from the south and and south west and the prevailing south westerly gales. There began a long succession of wrecks, culminating in 1804 when, in one day, ten large vessels were driven ashore. The citizens of Plymouth didn’t mind, calling the wrecks their ‘Godsends’, a steady supply of plunder, but the Admiralty did. Many of the ships were theirs!

The journey could take five or six days – longer in winter. Anyway, Plymouth it was and for over a hundred years this was a base for the Home Fleet. But there was a problem – the Sound was completely unprotected from the south and and south west and the prevailing south westerly gales. There began a long succession of wrecks, culminating in 1804 when, in one day, ten large vessels were driven ashore. The citizens of Plymouth didn’t mind, calling the wrecks their ‘Godsends’, a steady supply of plunder, but the Admiralty did. Many of the ships were theirs!

In 1806 the Admiralty commissioned a study on how to build a breakwater, and work began in 1812. It was built across the tops of three separate outcrops of rock but, as these rocks were 60ft down, they had to make a solid underwater wall using the laborious process of taking large blocks of stone out to the rocks and dropping them into the water. These blocks formed the crude outside walls of the structure and they then filled in the gaps with tons of rubble. The first block was dropped from a sailing barge on 12th August 1812.

Today this seems all very hit and miss but by spring of 1813 some of the blocks were visible on a big spring tide. The stone blocks were quarried locally but the cutting out of these huge blocks was in itself a laborious process – until along came our friend Richard Trevithick. He devised a steam-powered drill which vastly speeded up the process. Blocks, which used to cost 2s 9d a ton under the original method fell to 1s a ton once steam was introduced.

The idea was that the blocks should be dropped as near as possible in two parallel lines along the top of the rocks. They then dropped rubble on top of that hoping that it would sink down and plug the cracks. Gravity and the action of the sea swilled the rubble around and the result was a rough wall of blocks with a solid rubble infill. This apparently haphazard system worked and by mid 1813 they had a wall at tide level. It was still necessary to add more rubble from time to time to make up for settlement and wave action.

As they had a wall, which was above water level, they could start work in a more conventional way, dovetailing blocks and using cement. Now, however, came a new problem – it seemed they had created a hazard to shipping! Vessels began to get wrecked on the large unmarked obstruction as they made their way into and out of Plymouth. The local merchants and ship-owners were not amused so the next thing they had to do was to build was a lighthouse at the western end of the breakwater and a pole beacon at the eastern end. This had an iron globe on the top, the idea being that a shipwrecked mariner could climb up into it to await rescue.

As they had a wall, which was above water level, they could start work in a more conventional way, dovetailing blocks and using cement. Now, however, came a new problem – it seemed they had created a hazard to shipping! Vessels began to get wrecked on the large unmarked obstruction as they made their way into and out of Plymouth. The local merchants and ship-owners were not amused so the next thing they had to do was to build was a lighthouse at the western end of the breakwater and a pole beacon at the eastern end. This had an iron globe on the top, the idea being that a shipwrecked mariner could climb up into it to await rescue.

The breakwater was officially completed in 1848 and by then 3 ½ million tons of limestone had been dropped. Even then there has been a continual need for repairs and additional stone to be dropped to fill in cracks and crevices from time to time. Even after completion it still attracted casualties, usually in bad visibility. Remember that in the days before the Second World War RADAR did not exist and they had no electronic aids.

Ships approaching Plymouth were doing so solely on visibility, relying on the lookouts in the crow’s nest, high up on a mast. This was the case even with ships of the Royal Navy. They might well know where they were by accurate navigation but the final run in relied on being able to see the shore in daylight or lights at night. Given a dark night or poor visibility they had to avoid a low structure which was about half a mile long, solid stone with about a quarter mile gap at either end. It was small wonder that there was a steady succession of casualties. The last shipwreck was a hopper barge in 1913.

There is, however, one final rather tragic storey. On the night of 13th February 1943, there had been a raid on the U-Boat pens at Lorient. Seven aircraft were lost in the raid and another Lancaster was severely damaged. The Pilot, Flight Sergeant Gifford Miller, was struggling to get his Lancaster back to England and reached the coast intending to make an emergency landing at RAF Harrowbeer, just north of Plymouth. The plane was losing height and struck the cable of a barrage balloon used to defend the Port. The Lancaster was ripped apart and came down into the sea close to the western end of the breakwater, where it lies to this day. All seven of the crew died, their bodies never recovered.

There is, however, one final rather tragic storey. On the night of 13th February 1943, there had been a raid on the U-Boat pens at Lorient. Seven aircraft were lost in the raid and another Lancaster was severely damaged. The Pilot, Flight Sergeant Gifford Miller, was struggling to get his Lancaster back to England and reached the coast intending to make an emergency landing at RAF Harrowbeer, just north of Plymouth. The plane was losing height and struck the cable of a barrage balloon used to defend the Port. The Lancaster was ripped apart and came down into the sea close to the western end of the breakwater, where it lies to this day. All seven of the crew died, their bodies never recovered.

So Plymouth Breakwater is the ideal example of a man made haven of which there are many in the world. They provide a good safe anchorage for larger vessels but can never match the security of a job done by Nature. Anyone who sails a small boat in our local waters will tell you that Falmouth is a far snugger place than Plymouth unless you go well up the rivers. From our Lookout we are unable to see into either Falmouth or Plymouth though, on a very clear and calm day, it is possible to see as far as Rame Head near the Plymouth entrance.

What we do see, however, is the stream of yachts passing a mile or so off shore on their way between Falmouth, Fowey and Plymouth, yachts which we try to identify and record in our log. Occasionally one gets into trouble, propeller fouled in a net, engine failure or broken rigging. All of these can be a serious problem causing the vessel to drift onto rocks or a mast to come crashing down. The casualty will usually call the Coastguard with their problem but the Coastguard cannot see them because of the lay of the land. We are often called by the Coastguard to ask if we can see the causality, then asked to keep an eye on the situation and, perhaps, to help guide the Lifeboat to the scene.

That, really, is what we do. We are, if you like, the ‘guardian angel’, hopefully not needed but, if trouble strikes, we are in a position to get help. Though I have talked about yachts the same applies to fishing boats, inflatables, kayakers, swimmers and anyone using the sea. Most of our work comes on fine days, so good weather is not really a guarantee that nothing can go wrong. A fine day and an offshore wind will see an inflatable toy decide to strike out for France taking with it a hapless child. A helpful wind pushing the paddle boarder past the Lookout into Gerrans Bay will turn out to be an implacable obstacle when you want to get back to Porthcurnick.

Several times each year we get involved in what, hopefully, are minor incidents. We arrange for a local boat to ferry petrol out to a broken down RHIB, we keep an eye on a very tired lady trying to get back to Porthcurnick or we tell the Coastguard of a helplessly drifting dinghy which needs the Inshore Lifeboat. But we still don’t have enough volunteers to cover all the hours we would like. It’s a worthwhile cause among a congenial bunch of men and women. That phone number hasn’t changed. It’s 01872-530500 for Sue and 01326-270681 for Chris.

Pictures courtesy of Wikepedia