The winter weather has at last arrived – thank Goodness! I ‘m always a lot happier when the cold weather sets in (happier for the bees, if not for myself!) as it means the bees will cluster together more tightly, eat less food (just enough to keep themselves warm) and not try flying out of the hive. The bees that enter the winter period have prepared themselves for the long stay indoors by building up their fat-bodies in the months prior to Christmas so that they can live longer than usual.

The winter weather has at last arrived – thank Goodness! I ‘m always a lot happier when the cold weather sets in (happier for the bees, if not for myself!) as it means the bees will cluster together more tightly, eat less food (just enough to keep themselves warm) and not try flying out of the hive. The bees that enter the winter period have prepared themselves for the long stay indoors by building up their fat-bodies in the months prior to Christmas so that they can live longer than usual.

In the summer months, bees only live for about 6 weeks, whereas in the winter (assuming it is cold and they are clustered inside the hive) they have to (and can) live for up to 6 months, but if the weather is mild they will fly out looking for forage and wear their wings out – as well as eating all their stores because they are more active. This means they will die in less than the allotted 6 months and, with the queen not laying eggs to replace the dead bees, the colony will dwindle to a point where it cannot sustain itself and will die. It is an especially worrying time for us beekeepers when the winter is mild but if this cold spell lasts we should make it to the point where the queen increases her laying (with the longer days) to make up for any losses from premature flying.

In the meantime, beekeepers like myself are preparing for the season ahead by cleaning our equipment and making ready for the new season by furthering our beekeeping knowledge (there is always something new to learn!) through reading and attending workshops. We had such a workshop last Saturday, on “Queen Rearing”. This is a subject dear to my heart, as I rear my own queens and do not import foreign races from overseas as some beekeepers do. The reason for this is manifold.

Firstly, I can breed queens from stock whose characteristics I am familiar with and desire, such as hygienic traits, docility and non-aggressiveness, good nectar gathering (especially in damp weather), prolificacy (the ability to raise large colonies) and disease resistance. With imports of foreign queens, you never know for sure about any of these characteristics – especially disease resistance and hardiness – so it is far better to raise your own, local, queens and be guaranteed that they come from stocks (that you have chosen) which have these characteristics. There are many methods of rearing queens but I favour two, one called the Miller method and another known as the Hopkins method (top Pic). Both of these rely on the bees’ fundamental requirement to have a queen in the colony – without one the colony will die – and each has its merits and devotees.

Firstly, I can breed queens from stock whose characteristics I am familiar with and desire, such as hygienic traits, docility and non-aggressiveness, good nectar gathering (especially in damp weather), prolificacy (the ability to raise large colonies) and disease resistance. With imports of foreign queens, you never know for sure about any of these characteristics – especially disease resistance and hardiness – so it is far better to raise your own, local, queens and be guaranteed that they come from stocks (that you have chosen) which have these characteristics. There are many methods of rearing queens but I favour two, one called the Miller method and another known as the Hopkins method (top Pic). Both of these rely on the bees’ fundamental requirement to have a queen in the colony – without one the colony will die – and each has its merits and devotees.

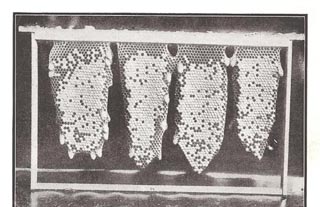

The Miller method (pic above) gives bees a section of comb shaped to allow the production of queen cells (in which the new queens develop) without impinging one against the next. A frame containing sections of wax foundation is given to one’s best colony, which then draws comb on these sections, allowing the queen to lay eggs in this. The queen, however, can only lay in cells that are complete, so as the sections of comb are extended, she will lay in the completed parts and await completion of the rest before continuing. This means that the outside edges of each of these sections will contain eggs and the cells just inside this outer edge will contain newly-hatched larvae.

By removing the frame from the hive and cutting away the outer edges of the sections, we end up with a series of appropriately-aged larvae right on the edges of the comb. This comb is then given to a colony which has been made queen-less (or has been kidded into thinking it is queen-less – but that’s another story!) and the bees will draw queen cells down from the cells on the outer edges of the comb, thereby creating a series of queen cells which are free-hanging and not impinging on each other. Two days before the queens are ready to emerge, the frame is removed from the hive and the queen cells are carefully cut off the comb (that’s why it’s important that they don’t impinge on each other) and inserted into queen-less nuclei or mini-nuclei established a few hours before. The queens will emerge two days later, will mate and eventually start laying, and once it is established that the laying pattern is sound and there is no disease or other undesirable qualities about the brood or the queen, she can be introduced into a full colony that needs to be re-queene.

By removing the frame from the hive and cutting away the outer edges of the sections, we end up with a series of appropriately-aged larvae right on the edges of the comb. This comb is then given to a colony which has been made queen-less (or has been kidded into thinking it is queen-less – but that’s another story!) and the bees will draw queen cells down from the cells on the outer edges of the comb, thereby creating a series of queen cells which are free-hanging and not impinging on each other. Two days before the queens are ready to emerge, the frame is removed from the hive and the queen cells are carefully cut off the comb (that’s why it’s important that they don’t impinge on each other) and inserted into queen-less nuclei or mini-nuclei established a few hours before. The queens will emerge two days later, will mate and eventually start laying, and once it is established that the laying pattern is sound and there is no disease or other undesirable qualities about the brood or the queen, she can be introduced into a full colony that needs to be re-queene.

Alternatively, the new queen can be left with the nucleus – though not a mini-nucleus – and a new colony started from that. The Hopkins method is similar to the Miller, except that this uses a full comb, laid up by your best colony, and placed horizontally on top of your queen-less colony, so the bees can draw the queen cells vertically downwards but in greater number (because there’s more room for the greater number of cells). To accommodate these queen cells, I need a lot of nucleus boxes, so am busily cleaning and sterilising mine in readiness. As I’ve said before, there’s no let-up in beekeeping!

Colin Rees – 01872 501313 – colinbeeman@aol.com