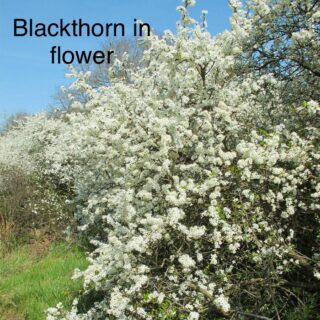

So, the blackthorn is starting to flower already! This means the bees have now an abundance of nectar as well as pollen available to start the new season. Once we get to this point, I breathe a sigh of relief because the most difficult time in the bees’ annual cycle is just about over (though we are promised colder weather over the next few days). Whilst pollen has been freely available over the past few months, mainly from gorse, it is the availability of nectar at this time of year that is most important. The queen, recognising that the days are getting longer and that the ambient temperature is rising, will be starting to gear up her laying rate. Up until now she has only been laying perhaps a dozen eggs a day during the darkest days, a number which has no doubt increased in the past month to perhaps scores of eggs. Once these eggs hatch into larvae they will need feeding with what is known as brood food, a secretion from the bees’ mandibular glands mixed with pollen and honey, so availability of nectar is key.

So, the blackthorn is starting to flower already! This means the bees have now an abundance of nectar as well as pollen available to start the new season. Once we get to this point, I breathe a sigh of relief because the most difficult time in the bees’ annual cycle is just about over (though we are promised colder weather over the next few days). Whilst pollen has been freely available over the past few months, mainly from gorse, it is the availability of nectar at this time of year that is most important. The queen, recognising that the days are getting longer and that the ambient temperature is rising, will be starting to gear up her laying rate. Up until now she has only been laying perhaps a dozen eggs a day during the darkest days, a number which has no doubt increased in the past month to perhaps scores of eggs. Once these eggs hatch into larvae they will need feeding with what is known as brood food, a secretion from the bees’ mandibular glands mixed with pollen and honey, so availability of nectar is key.

Relief all round then! Mind you, I am still providing fondant as an emergency source of energy for the bees but, as usual, some colonies are totally ignoring it and relying totally on their winter stores. This means they also need water to dilute those stores to a point at which it can be assimilated by themselves and by their larvae. To that end, my bird-bath is being kept topped up so the bees don’t have to travel far to find this important resource.

Unfortunately, I have lost another colony recently – it was in the tree bait hive that I failed to find time to relocate. This was a small swarm that has been performing well over winter and into the early New Year but, despite my best efforts, succumbed to the presence of shrews – even though it was high up in a tree! Shrews can get through the smallest gap and are more of a nuisance to me than mice, as I have seen evidence of their presence on the tops of my crown-board insulation in another three hives. The little blighters even have the audacity to chew saucer-shaped hollows in my insulation and build their nest in those hollows! Luckily, this is generally not a problem

to the bees as the scratching and movement of the shrews is not sufficient to disturb them, but once inside the brood box they will destroy the combs whilst building their nest. Having said that, though – they are quite cute!

Whilst my beekeeping so far this year has not yet extended to the bees, other than ensuring they have food and that their hives are upright and the rooves are in place, I have been cleaning and repairing frames, as well as cleaning out the brood boxes from the colonies that died, ready for the season ahead – some of the many winter tasks that need to be done in readiness for the Spring. I’ve also been preparing wax for my customers who seem to need an endless supply, so that also keeps me occupied.

Whilst talking about checking that hives are upright, after the three storms we had in March I did indeed find some minor devastation as a result. At home, two hives were tilted off their stands whilst two others had their hooves blown off.

One of them not only lost its roof but also its insulation and the plastic container that held the fondant, thereby making the fondant freely available to any passing bee. Bees being opportunists, took advantage of this “free meal” and the fondant was covered in scores of bees from neighbouring hives.

One of them not only lost its roof but also its insulation and the plastic container that held the fondant, thereby making the fondant freely available to any passing bee. Bees being opportunists, took advantage of this “free meal” and the fondant was covered in scores of bees from neighbouring hives.

Even after I re-instated the fondant cover, the insulation and the roof, there were bees trying to get into the roof cavity for the next two to three days – the robbers had gone back to their hives and told their sisters about what they’d found and where it was, so bees kept on coming to try to find the food source at the location described.

Even after I re-instated the fondant cover, the insulation and the roof, there were bees trying to get into the roof cavity for the next two to three days – the robbers had gone back to their hives and told their sisters about what they’d found and where it was, so bees kept on coming to try to find the food source at the location described.

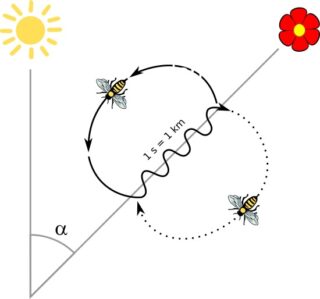

So how do the bees communicate this information to their fellow-foragers? How did the robber bees know where the food source was? It’s location is communicated by means of a dance, commonly known as the “figure of eight” or “waggle” dance, which the bees perform on the surface of the comb. Now, you should remember that the inside of the hive is in darkness so the bees can’t see this dance, they have to feel it. The bees have their six legs spread out on the surface of the comb and it is the vibrations of the dancing bee/s that is picked up through the legs of the “watching” bees. This is why I stress to my students that kicking the hive, whether accidental or not, throwing combs around, banging the hive as combs are being removed for inspection, etc is just not on. Such cavalier behaviour not only stresses the bees, potentially making them susceptible to disease, but prevents them from correctly interpreting the details of the dance.

So, the bees “see” the figure of eight dance and note the direction of the straight part between the two circles of the figure eight. The direction of this tells the bees the direction to fly when they leave the hive. If the figure of eight is lying horizontally, ie on its side, with the straight part vertical, ie running up and down on the face of the comb, and the bee is moving upwards along the straight part, that tells the bees to fly in the direction of the sun on leaving the hive. If the figure of eight is at an angle to the horizontal then that angle is the direction the bees fly, relative to the sun again, on leaving the hive. Additionally, the sun is not a static heavenly body. As it moves across the sky, so do the bees adjust the angle of their dance to reflect this. Finally, how far must they fly? That is determined by the length of time it takes the dancing bee to traverse the straight section and the amount of waggle its abdomen performs whilst doing so. If the waggle is rapid and the traversing time is fast, then that means the forage is nearby, though generally more than about 40 metres away. A longer duration, stately meander along the straight section indicates the forage is even further afield. It is therefore the duration of this part of the dance that gives the precise distance the bees have to fly to the forage. Quite miraculous, really.

So, the bees “see” the figure of eight dance and note the direction of the straight part between the two circles of the figure eight. The direction of this tells the bees the direction to fly when they leave the hive. If the figure of eight is lying horizontally, ie on its side, with the straight part vertical, ie running up and down on the face of the comb, and the bee is moving upwards along the straight part, that tells the bees to fly in the direction of the sun on leaving the hive. If the figure of eight is at an angle to the horizontal then that angle is the direction the bees fly, relative to the sun again, on leaving the hive. Additionally, the sun is not a static heavenly body. As it moves across the sky, so do the bees adjust the angle of their dance to reflect this. Finally, how far must they fly? That is determined by the length of time it takes the dancing bee to traverse the straight section and the amount of waggle its abdomen performs whilst doing so. If the waggle is rapid and the traversing time is fast, then that means the forage is nearby, though generally more than about 40 metres away. A longer duration, stately meander along the straight section indicates the forage is even further afield. It is therefore the duration of this part of the dance that gives the precise distance the bees have to fly to the forage. Quite miraculous, really.

Here endeth the lesson! I hope you find such information as fascinating as I do. The honey bee is a cornucopia of amazement which is partly why it is so precious in my eyes. The fact that, according to Einstein or perhaps some folklore-ish tale, that if the honey bee dies out then mankind will follow shortly after is quite credible when one thinks of how the honey bee contributes to our diet through pollination services. So let’s all help the honey bee by planting and sowing crops that not only provide us with food and beauty but also help the honey bee to survive – as well as ourselves!

Finally, a reminder about (yes – again!) Asian Hornets.

The over-wintered queens are now coming out of hibernation and will be looking to establish new nests for the coming season. Please keep your eyes peeled for the distinctive colouring of what might casually be taken for a queen wasp

(of which many are also coming out of hibernation now and also looking to build new nests) and get in touch if you see one (Asian Hornet, that is). Otherwise, send an email to alertnonnative@ceh.ac.uk

Until next month then, enjoy the promise of the arrival of Spring.

Colin Rees 07939 971104 01872 501313 colinbeeman@aol.com