What On Earth Is That On The Horizon

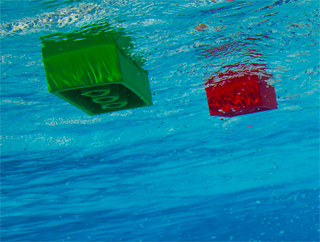

It lies out there, a giant floating box, seemingly stationary, a Lego piece thrown by a petulant child. There are a few ships about but none seem to have any interest so, perhaps, it is an optical illusion. There is a tiny dot some distance away which also looks stationary. Too far out to be logged and, in any case, Lego bits and pieces do not feature in our master plan covering log entries.

It lies out there, a giant floating box, seemingly stationary, a Lego piece thrown by a petulant child. There are a few ships about but none seem to have any interest so, perhaps, it is an optical illusion. There is a tiny dot some distance away which also looks stationary. Too far out to be logged and, in any case, Lego bits and pieces do not feature in our master plan covering log entries.

Forget about it and continue my routine search closer inshore. Looking again after ten minutes I realise that the bearing has changed and it is moving slowly towards Falmouth. The big telescope can make out that is dirty grey in colour with a few bits and pieces which could be cranes or derricks. The small dot is pushing foaming water out behind it – a tug and tow, possibly a floating dock or something to do with the oil industry.

Ever since man first went on the water there has been a need to move things which did not have their own power. The Romans and the Greeks, no mean seafarers, no doubt put heavy loads on to barges which they towed by oar power. There is a disputed theory that the stones at Stonehenge were transported from South Wales by raft across the Severn. There is no doubt whatsoever that, from the time of Alfred’s navy, large ships were towed out of difficult places by means of rowing boats used as tugs though there was a limit to how far they could be pulled and the conditions in which this could be done.

The last thing you would want would be several hundred tons of ship taking charge as it moved out of a sheltered berth into a wind. A skilled ship master in favourable conditions could sail his ship off many berths or else they could be warped out. This involved carrying an anchor out some distance from the ship, dropping it, and the ship then winching the anchor in on its capstan. Heavy, slow and laborious work.

In 1736 Jonathan Hulls of Gloucester patented the first tug boat using the new fangled idea of steam power. The idea never really got off the ground and it was not until 1802 that the first practical one was built called the Charlotte Dundas. She again used steam to power a stern paddlewheel and was intended for use on the Forth Clyde Canal in Scotland.

They did a test run and she proved herself by hauling two 70 ton barges the length of the canal, a job undertaken before by bank side horses. Even then the idea did not take off as the canal authorities were afraid that her wash would damage the canal banks. She never went in to regular service. It was not until 1817 that the first successful tug was built on the Clyde as a ‘ship assistor’, to be followed two years later by the ‘Sampson’, the earliest named tug as we know them today.

Then the greatest tug boat nation of all entered the scene. The Dutch have vast areas of inland sea behind their dyke walls and it was a long and treacherous journey for a sailing ship to cross this and reach the ocean. Many grounded on shifting sandbanks when the winds were light or contrary. Once the tug concept became known in 1840 the Dutch embarked on a building programme, a fleet of small side wheel paddlers which would take ships out to sea and even down Channel as far as the Isle of Wight if the winds did not suit.

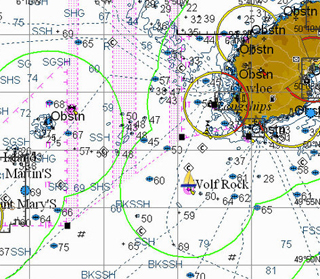

The tugs got bigger, designed now for sea towing, but no one went beyond the Bishop Rock off Lands End. They began to export them, taking them apart and putting them on large ships, re-assembled in foreign ports to be used as harbour tugs. No one thought they were truly seaworthy until the difficulties of assembling them properly in foreign ports with unskilled labour became too much. There was only one solution. Build a bigger tug that could tow them.

The tugs got bigger, designed now for sea towing, but no one went beyond the Bishop Rock off Lands End. They began to export them, taking them apart and putting them on large ships, re-assembled in foreign ports to be used as harbour tugs. No one thought they were truly seaworthy until the difficulties of assembling them properly in foreign ports with unskilled labour became too much. There was only one solution. Build a bigger tug that could tow them.

The first man to take a tow across the Atlantic in about 1895 towed a dredger to South America, returning full of tales of sea serpents and waves like cathedrals, but he was a known drunkard and his serpents got bigger as the evening went on. The fact remained that he had done it and the Dutch deep sea tug industry was born.

We occasionally see one of the latest Dutch or German tugs anchored off Falmouth, just in our view, large, squat vessels, sort of maritime all-in wrestlers, sitting there waiting for a casualty to rescue. There is usually one either off Falmouth or in Mounts Bay, a permanent stand-by vessel, and the frequency of the calls on their services is enough to keep the market going. Many are routine breakdowns, no one in any danger, just an inert hulk to pick up and tow in for repairs.

When we see a tug and tow on the horizon they look like two totally separate vessels. The tow line is invisible and, may be half a mile long – that is the distance between Pednavaden and Portscatho. The tug will shorten up if heading in to Falmouth but the line is so long for two reasons. The longer it is the more stretch it will have and this eases the strain on the line. Secondly a long line will produce a catenary, the dip caused by the weight of the rope over a long distance.

When we see a tug and tow on the horizon they look like two totally separate vessels. The tow line is invisible and, may be half a mile long – that is the distance between Pednavaden and Portscatho. The tug will shorten up if heading in to Falmouth but the line is so long for two reasons. The longer it is the more stretch it will have and this eases the strain on the line. Secondly a long line will produce a catenary, the dip caused by the weight of the rope over a long distance.

This acts as a spring and eases the shocks on the towing gear. Tugs actually do not tow from the stern but from a point about one third of the tugs length from the stern. This is to allow the tug to steer. If the line was attached to the stern then the tug stern could not swing because of the weight. By moving the line inboard the stern can swing out to the desired side, thus allowing the bows to point in the new direction.

This weekend, 20th August, has been a bad day around the UK coasts. Eight people have drowned in various places. One cannot say that NCI watchers might have saved them but it does highlight how dangerous the sea can be even when conditions seem benign. This is the time when people relax, let their guards down, cease their natural caution and take a risk which does not seem a risk to them.

I have a picture taken last week on a fine sunny day. Two adults are on paddleboards – those thing like a surfboard but on which you stand up and paddle with a long oar. As they went past the Lookout towards Pendower our Watchkeepers realised that the mother (?) was carrying a passenger – a child aged about four! None of the three were wearing life jackets. Turning around they paddled back again but, just off the rocks of Pednvadan, they closed up and transferred the child from one board to the other with all the attendant wobbles.

I have a picture taken last week on a fine sunny day. Two adults are on paddleboards – those thing like a surfboard but on which you stand up and paddle with a long oar. As they went past the Lookout towards Pendower our Watchkeepers realised that the mother (?) was carrying a passenger – a child aged about four! None of the three were wearing life jackets. Turning around they paddled back again but, just off the rocks of Pednvadan, they closed up and transferred the child from one board to the other with all the attendant wobbles.

Benign conditions? – Yes. Did all end well? – Yes. Was it sensible? Well our Watchkeepers were concerned and breathed a sigh of relief when they finally reached Porthcurnick. I suppose that is why we are there, to be a safety net for when things go wrong.

We have gained four newly qualified Watchkeepers so, hopefully, next year will find manning our shifts easier for John who does the organises the system. We still need more if we are to reach our target, enough people to cover every day of the week. It’s not difficult and the skills required are passed on by our Training Team. Find out more about it – give Sue a ring on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681.