PASS THE ICELANDIC SPAR, PLEASE

One thing we take for granted in the Lookout is the chart. Because we only cover the area the eye can see our charts are large scale, the area from Nare Head to Falmouth, and up to about five miles offshore. That is sufficient for our needs but most of the yachts sailing by will be carrying at least one full sized chart, perhaps going from Plymouth as far west as the Lands End. Many will carry a far greater selection to cover their proposed cruising grounds of France or Ireland. Ships, though, may carry a full set of worldwide Admiralty Charts, perhaps a hundred or so – and even that will not include every chart that the Admiralty Chart Service produces!.

One thing we take for granted in the Lookout is the chart. Because we only cover the area the eye can see our charts are large scale, the area from Nare Head to Falmouth, and up to about five miles offshore. That is sufficient for our needs but most of the yachts sailing by will be carrying at least one full sized chart, perhaps going from Plymouth as far west as the Lands End. Many will carry a far greater selection to cover their proposed cruising grounds of France or Ireland. Ships, though, may carry a full set of worldwide Admiralty Charts, perhaps a hundred or so – and even that will not include every chart that the Admiralty Chart Service produces!.

Charts have been about for centuries. The first nautical charts were produced in mid-thirteenth century but the earliest recognised navigators were the Phoenicians, the Polynesians and later the Norsemen. To begin with they simply followed the coastline but the natural inclination to explore and see what is over the horizon soon drove them further field. Navigational ‘tools’ were the sun and the stars and once they knew where North was the rest fell in to place.

This worked well in the often cloudless Mediterranean but not so for the Norsemen as in the northern latitudes neither sun nor stars can be relied on. They learnt to read the wave type and direction and studied birds. If a sea bird was flying past with its beak full it was heading home to land. If the beak was empty it was on its outward journey. One Norwegian kept ravens on board his vessel which he starved. When he thought he was near land he would release a bird and see which way it flew. The land around the Mediterranean was well charted and the Norse knew the British Islands and the European coasts so quite long voyages were accomplished.

This worked well in the often cloudless Mediterranean but not so for the Norsemen as in the northern latitudes neither sun nor stars can be relied on. They learnt to read the wave type and direction and studied birds. If a sea bird was flying past with its beak full it was heading home to land. If the beak was empty it was on its outward journey. One Norwegian kept ravens on board his vessel which he starved. When he thought he was near land he would release a bird and see which way it flew. The land around the Mediterranean was well charted and the Norse knew the British Islands and the European coasts so quite long voyages were accomplished.

The commonest, most long lasting navigational tool was the lead, a seven or eight pound lump of lead with a hollow in the bottom attached to a long line. This was filled with tallow or grease. A man would stand in the bows of the ship and throw it forward so that by the time it hit the bottom the ships motion would mean it was just about vertical. The line was marked with bits of leather so the leadsman could read the depth of water.

The tallow in the base would pick up a sample of the sea bottom so the Captain could tell what was underneath his ship – mud, sand, shell, etc. If he was an expert navigator that would give him a good idea as to where he was. Admittedly because of the limits of the length of the line, it would always be fairly shallow water. In the North Sea of course there are extensive sandbanks, too far out to be able to see land in poor visibility. Even in fairly recent years the North Sea fishermen could tell where they were by this means – smelling or, perhaps, even tasting the sample!

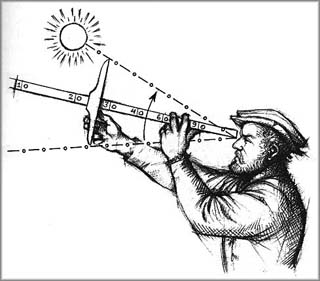

To go further afield one had to read the sun and the stars. All sorts of devices were invented to give more accurate readings of one’s position. The cross staff was simply a long piece of wood with gradations marked up in. Sliding up and down on this shaft was another piece of wood at right angles. To measure the angle of the sun or a star you looked along the shaft and then moved the cross piece until its tip covered the star.

To go further afield one had to read the sun and the stars. All sorts of devices were invented to give more accurate readings of one’s position. The cross staff was simply a long piece of wood with gradations marked up in. Sliding up and down on this shaft was another piece of wood at right angles. To measure the angle of the sun or a star you looked along the shaft and then moved the cross piece until its tip covered the star.

You could then read the angle off the gradations A far more ingenious device was the Iceland spar or Norse sunstone, a simple square piece of transparent crystal. On a cloudy day when the sun was not readily visible you could look through this to where the sun should be and it would polarise the available light to one spot and tell you where the sun actually was.. It is with this that some people believe the Norsemen navigated to North America long before Columbus.

The great step forward was the invention of the compass. The Chinese had invented a form of compass by using a lodestone in the eleventh century. It is interesting to note that this pointed to the south, not north as a magnetic compass does. That didn’t matter – so long as you knew which direction south was you could work the rest out. Actually though the main use of a Chinese compass was in divination and fortune telling, so you could be buried in the right direction or find the best place to get married.

Experiments in the use of a magnetised needle began in Europe in the 12th century but it was another hundred years before its use became general around the Mediterranean. Coastal charts were being drawn and used together with the compass the cruising season in the Mediterranean could be extended to a full twelve months – no longer were clear skies necessary. So what today we regard as commonplace essentials have a long history. So far as we in the Lookout are concerned without chart and compass bearings we could not direct the Lifeboat to a casualty. Without them the Lifeboat would be unable to find a casualty!

Experiments in the use of a magnetised needle began in Europe in the 12th century but it was another hundred years before its use became general around the Mediterranean. Coastal charts were being drawn and used together with the compass the cruising season in the Mediterranean could be extended to a full twelve months – no longer were clear skies necessary. So what today we regard as commonplace essentials have a long history. So far as we in the Lookout are concerned without chart and compass bearings we could not direct the Lifeboat to a casualty. Without them the Lifeboat would be unable to find a casualty!

There are times though when accurate plotting is not the complete answer. Just towards the end of the season Peter and Sue were in the Lookout when a call was heard on Channel 16 to the effect that a yacht was on fire in the bay. The position was given and they plotted it on the chart – about four miles out, towards the limit of visibility without binoculars. The Coastguard came up and asked if they could see the casualty but, even using our big telescope, they had to say they could not find it.

The helicopter was scrambled and shortly after Rescue 924 came on the scene. He was able to go to the plotted position and, once he was hovering, the Watchkeepers were able to make out a dark blob on the sea underneath. A dark blue hull is surprisingly difficult to make out at that distance against a dark coloured sea, but at least the Watchkeepers could feel that they had got the position right and, had they been the only ones to pick up the call, they had enough information to pass on to the Coastguard.

With two lifeboats in attendance the I.L.B. made a quick run alongside and the lone crewmember of the yacht jumped in. He was transferred to the All Weather Boat and the helicopter released to go to another rescue.

With two lifeboats in attendance the I.L.B. made a quick run alongside and the lone crewmember of the yacht jumped in. He was transferred to the All Weather Boat and the helicopter released to go to another rescue.

This was the first occasion when any of us have had the chance to see the new Coastguard helicopter in action – and what a big beast it is. With greater range, greater carrying capacity, greater speed and longer hours in the air it shows every sign of being a success. With all those advantages over the long serving Sea King there is still one other facility that the Sea King could not match. It is a flying ambulance with a full medical suite.

The paramedics it carries can now work in some comfort and with better facilities than before when much of the life saving in the air was done on a stretcher on the floor. This can only be good and increase the survival chances of a casualty on his way to hospital. Note the new call sign number – Rescue 924.

By the time this is published we shall be in the New Year, working up to another season in the Lookout. It is a shame we can only man the place on six days of the week, as we have not enough volunteers. You could do something about that. Male or female, young or old, retired or working we really need your help. It is not difficult and proper training is given. We are a sociable group. Give Sue a ring on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681. You can then come down to one of our monthly meetings and see for yourself that we are really a bunch of ordinary people trying to do something to help.

Pictures by courtesy of Wikepedia and H.M. Coastguard