Whilst January is a quiet month for the bees, it is not so quiet for the beekeeper! During the past few weeks I have been busy on several “out of season” tasks, amongst which have been included building an extra-large brood box (known as a “Jumbo” brood box) in readiness for the season ahead, making and bottling some “soft-set”, or “creamed”, honey, and melting and filtering accumulations of wax that have built up through the season.

Whilst January is a quiet month for the bees, it is not so quiet for the beekeeper! During the past few weeks I have been busy on several “out of season” tasks, amongst which have been included building an extra-large brood box (known as a “Jumbo” brood box) in readiness for the season ahead, making and bottling some “soft-set”, or “creamed”, honey, and melting and filtering accumulations of wax that have built up through the season.

The idea of the Jumbo brood box is to replace the British Standard brood box, which was designed at a time when the British Black Bee was the indigenous specie of honeybee in the UK. Nowadays, however, our bees are more like mongrels, crosses between bees from Italy, Greece, Turkey, France, the lower Russian Steppes and from Eastern Europe.

The result is that colonies tend to be a lot larger now than they were back in the early 20th Century, when a disease called, at the time, “Isle of Wight Disease”, virtually wiped out our own native bee and we had to replace our lost stocks with imports. This means that inevitably the British Standard brood box is now too small for the colony’s needs, and under the pressure of limited brood space for the queen to lay eggs, colonies are more prone to swarming

The result is that colonies tend to be a lot larger now than they were back in the early 20th Century, when a disease called, at the time, “Isle of Wight Disease”, virtually wiped out our own native bee and we had to replace our lost stocks with imports. This means that inevitably the British Standard brood box is now too small for the colony’s needs, and under the pressure of limited brood space for the queen to lay eggs, colonies are more prone to swarming

One of the main objectives of a beekeeper’s craft is to prevent his/her bees from swarming, as such an occurrence results not only in non-beekeepers potentially being frightened by the sight and sound of the swarm, or being inconvenienced by having a swarm pitch in a tree in their garden or on the washing-line, but also in a loss of half the beekeeper’s bees and the whole of the honey harvest for that year.

But beekeepers are not acting selfishly, or in a non-sustainable or unnatural way, by preventing swarming – they are taking action which makes the bees think they’ve swarmed, as it’s instinctive for bees to want to propagate their species and if they think they haven’t swarmed when they want to, they will carry on trying until successful. So if we try to thwart the bees’ intent in a way which doesn’t satisfy their need, we are wasting our time and the bees will go regardless. But if we remove the space constraint in the hive, it is less likely the bees will want to leave. Hence the “Jumbo” brood box, which gives about 50{c8c3b3d140ed11cb7662417ff7b2dc686ffa9c2daf0848ac14f76e68f36d0c20} more space for the queen to lay her brood.

But beekeepers are not acting selfishly, or in a non-sustainable or unnatural way, by preventing swarming – they are taking action which makes the bees think they’ve swarmed, as it’s instinctive for bees to want to propagate their species and if they think they haven’t swarmed when they want to, they will carry on trying until successful. So if we try to thwart the bees’ intent in a way which doesn’t satisfy their need, we are wasting our time and the bees will go regardless. But if we remove the space constraint in the hive, it is less likely the bees will want to leave. Hence the “Jumbo” brood box, which gives about 50{c8c3b3d140ed11cb7662417ff7b2dc686ffa9c2daf0848ac14f76e68f36d0c20} more space for the queen to lay her brood.

Moving on to the “creamed” honey. Granulated, or “set”, honey results from nectar that is high in glucose content, e.g. oilseed rape, ivy, brassicas, etc. and generally sets rock hard – like concrete! The only way to eat this is by scraping layers of the concrete (sorry, set honey!) out of the jar – try putting a spoon in the jar to ladle out the honey and one is reminded of Yuri Geller!

To obtain a more spreadable, soft-set, honey, I take a 30lb tub of essentially runny honey that has set (all honeys eventually set, whether after 3 weeks, 3 months or 3 years) and bring it back to a softer state by gently warming it – not to the point where it is runny honey again but until it has a creamy consistency. I then add 3lb of warmed (again, back to a creamy state), granulated honey to the 30lb tub and mix the two honeys thoroughly, being careful not to incorporate an excessive amount of air in the process.

To obtain a more spreadable, soft-set, honey, I take a 30lb tub of essentially runny honey that has set (all honeys eventually set, whether after 3 weeks, 3 months or 3 years) and bring it back to a softer state by gently warming it – not to the point where it is runny honey again but until it has a creamy consistency. I then add 3lb of warmed (again, back to a creamy state), granulated honey to the 30lb tub and mix the two honeys thoroughly, being careful not to incorporate an excessive amount of air in the process.

The difference between the two honeys is that the granulated honey has larger crystals than the runny honey and when the two types are thoroughly mixed, the larger crystals are broken up into smaller ones which act as nuclei for the crystallisation process to start again, but based on these finer crystals, thereby giving the end result a softer, creamier consistency.

The result can be seen in the picture – jars of buttery, spreadable honey that has all the qualities of run honey except that it stays on the knife! Notwithstanding, there is still a large proportion of my customer base which prefers the “concrete” the bees sometimes produce, so I try to produce all three types. However, I have to say that to have a soft-set honey which has the taste of runny honey is a big plus to my way of thinking.

The result can be seen in the picture – jars of buttery, spreadable honey that has all the qualities of run honey except that it stays on the knife! Notwithstanding, there is still a large proportion of my customer base which prefers the “concrete” the bees sometimes produce, so I try to produce all three types. However, I have to say that to have a soft-set honey which has the taste of runny honey is a big plus to my way of thinking.

Finally, the wax. During the active beekeeping season, beekeepers accumulate unbelievably large quantities of wax. This is from wax scraped from the tops of frames in the brood chamber or from the recycling of brood combs to reduce the potential disease burden inside the hive. This wax is initially melted in an outdoors solar extractor but inevitably the resulting wax has impurities in it, like propolis or pupal cocoons.

So what I have been doing recently is to take this “dirty” wax and place it on a muslin or netting filter, laid inside a sieve (dedicated to wax processing, not from the kitchen cupboards!). This sieve is then placed on top of a Pyrex bowl containing a little water and the whole is placed in the warming oven of the Aga for a few hours (a low oven at about 60°C). The wax melts, percolates through the muslin filter, and floats on top of the water.

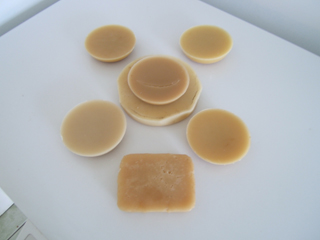

Any water-soluble impurities that pass through the filter dissolve in the water, the molten wax floats on top of the water, the heavier contaminants remain in the muslin and when the wax has all melted through to the bowl, the whole is removed and cooled. The wax will cool and solidify in a matter of hours and can be removed as a disc of clean, pure beeswax, ready for use in cosmetics, soap or candle-making. Job done!

Any water-soluble impurities that pass through the filter dissolve in the water, the molten wax floats on top of the water, the heavier contaminants remain in the muslin and when the wax has all melted through to the bowl, the whole is removed and cooled. The wax will cool and solidify in a matter of hours and can be removed as a disc of clean, pure beeswax, ready for use in cosmetics, soap or candle-making. Job done!

None of the above is particularly time-consuming by itself but taken together one has to work like a manufacturing line – set the honey to warm, put the wax/bowl in the oven, do some wood-work, check the honey, check the wax, more wood-work, blend the honeys and break up the larger crystals ready for soft-setting, check/remove the wax, cool it, more wood-work – well, you get the picture!

Never; let anybody tell you that beekeeping is a seasonal craft – it can become a full-time occupation if you so choose (my wife thinks it is, in my case, though it’s not – yet!). Then there’s the reading and furthering one’s knowledge – 5 mins here, 5 mins there.

And what about the bees? Some days they are still flying – even bringing in pollen, which is a positive sign, as it could mean that the queen is already (or hasn’t even stopped) laying. I am feeding 2 hives to build them up for the rape but all my colonies appear to be very strong and have plenty of food, thanks to the long , mild autumn with the ivy flowering, so the feed I’m giving hasn’t even been touched as yet. Could be an interesting season ahead!

As ever, beekeepers thoughts are never far from their bees- even in the wet, windy, cold winter weather that we are experiencing these past few years. It’s the only thing that keeps us sane!!

Colin Rees 01872 501313 colinbeeman@aol.com