It’s been a couple of months since the last article, owing partly to travel abroad. Many people are travelling to the Roseland for holidays, prompting a reminder that other species need to travel considerable distances in pursuit of resources essential for their survival, let alone pleasure. In the skies above us the swifts (Apus apus) go screaming by in pursuit of prey, while swallows (Hirundo rustica) skim the fields with house martins (Delichon urbica) close by. In a few weeks they will return to Africa, along with many other avian species. The hirundines epitomise our understanding of migration but this behaviour takes place at virtually all scales of life. Within the Roseland’s broad range of habitats live all kinds of species that move around regularly from one location to another, ever in search of suitable resources.

It’s been a couple of months since the last article, owing partly to travel abroad. Many people are travelling to the Roseland for holidays, prompting a reminder that other species need to travel considerable distances in pursuit of resources essential for their survival, let alone pleasure. In the skies above us the swifts (Apus apus) go screaming by in pursuit of prey, while swallows (Hirundo rustica) skim the fields with house martins (Delichon urbica) close by. In a few weeks they will return to Africa, along with many other avian species. The hirundines epitomise our understanding of migration but this behaviour takes place at virtually all scales of life. Within the Roseland’s broad range of habitats live all kinds of species that move around regularly from one location to another, ever in search of suitable resources.

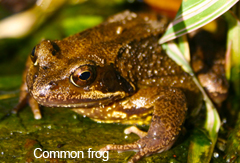

Now we have reached August, you may come across amphibians lurking in places where you might not expect to find them, quite some distance from any water source. Tiny frogs (Rana temporaria), common toads (Bufo bufo) and newts (Triturus spp.) that were produced this year have left the watery habitats where they started life. They join the adults who have also migrated to damp shady places, where their prey are hiding. This could be more than a mile away from where they began.

Amphibians feed on pretty much anything that moves and is the right size to swallow: a wide variety of soil invertebrates, arachnids and insects and even the tadpoles or eggs of other amphibians during the breeding season. Our gardens make great hunting grounds for these animals, who no longer need to be in or even near water out of the breeding season. The amphibian taste for slugs makes them a gardener’s friend. You will likely find newts hiding in log piles and composting material, while toads and frogs will dig themselves into anywhere cool and damp. Hollows under rocks and slabs are favourable sites. Even a Cornish hedge will be home to them if the resources are plentiful.

Amphibians feed on pretty much anything that moves and is the right size to swallow: a wide variety of soil invertebrates, arachnids and insects and even the tadpoles or eggs of other amphibians during the breeding season. Our gardens make great hunting grounds for these animals, who no longer need to be in or even near water out of the breeding season. The amphibian taste for slugs makes them a gardener’s friend. You will likely find newts hiding in log piles and composting material, while toads and frogs will dig themselves into anywhere cool and damp. Hollows under rocks and slabs are favourable sites. Even a Cornish hedge will be home to them if the resources are plentiful.

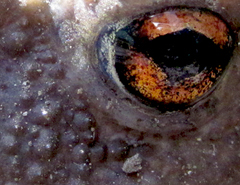

Toads have distinctly warty skin, unlike that of frogs, which is much smoother.

Toads have distinctly warty skin, unlike that of frogs, which is much smoother.

All our amphibia are cold-blooded and able to hibernate. Their energy requirements are relatively low compared to that of warm blooded mammals. They can remain dormant and away from water for long periods, until conditions favour the emergence of food resources and the breeding season. Climate in the Roseland, being generally mild, means that amphibians may never get to hibernate over some winters if prey also is about. On rainy dark nights watch out for them hopping and crawling along vegetation-rich pathways where they are easily trodden on.

Other Roseland creatures that travel far and wide are some of the tiniest mammals to be found in the UK today – the shrews. There are three species of shrew living in the UK mainland: the pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus), the common shrew (Sorex araneus) and the water shrew (Neomys fodiens), which is the largest of the three. Although similar to mice in appearance, shrews are in fact related to moles and hedgehogs and possess a number of primitive physiological features.

A notable feature is the dentition. Shrews have sharp pointed teeth which are specialised for a carnivorous diet. Water shrew teeth are even coated with a kind of venom that results in a painful wound if you should ever be bitten by one. By comparison, a typical rodent’s teeth are generalised for an omnivorous diet. Cheek teeth are much flatter for grinding large amounts of plant material.

A notable feature is the dentition. Shrews have sharp pointed teeth which are specialised for a carnivorous diet. Water shrew teeth are even coated with a kind of venom that results in a painful wound if you should ever be bitten by one. By comparison, a typical rodent’s teeth are generalised for an omnivorous diet. Cheek teeth are much flatter for grinding large amounts of plant material.

All shrews are said to be good swimmers, although it is only the water shrew which will dive considerable depths after prey, having hair and fur adaptations that help it to do so. Water shrews are also distinguishable from pygmy and common shrews by their near mouse-like size, long tail, black upper coat and pale grey underbelly. Pygmy and Common shrews are much harder to tell apart unless you have an adult example of each species side-by-side.

Unlike the amphibia, warm-blooded shrews have high energy needs and therefore cannot hibernate, needing to find food all through the winter. They must eat every two hours or so, otherwise they soon die. Diets generally consist of ground-dwelling invertebrates, occasionally carrion and very occasionally small quantities of vegetative matter. The diets of all three species largely overlap and it is size that mainly differentiates the prey eaten. Much of it consists of the same prey as that taken by ampibians.

Unlike the amphibia, warm-blooded shrews have high energy needs and therefore cannot hibernate, needing to find food all through the winter. They must eat every two hours or so, otherwise they soon die. Diets generally consist of ground-dwelling invertebrates, occasionally carrion and very occasionally small quantities of vegetative matter. The diets of all three species largely overlap and it is size that mainly differentiates the prey eaten. Much of it consists of the same prey as that taken by ampibians.

Shrews live principally at ground level and prefer a habitat rich in detritus and dense, vegetative cover. They have tiny eyes and very small ears, their most useful sense being smell. They easily fall prey to predators such as the tawny owl (Strix aluco) and barn owl (Tyto alba) whose silent approach easily outwits them when they are away from cover. Being relatively fearless and aggressive creatures, they are quite likely to be casually observed in broad daylight.

The preferred habitat of both the common and pygmy shrew throughout the British mainland is just about anywhere where dense herbage provides suitable cover and a ready supply of prey throughout the year. As well as hedges, deciduous woodland and grassland, they are happy to exploit scrubland and man-made garden habitats. I have lately observed a juvenile common shrew casually picking its way through fallen woody material in the garden, towards the end of July.

The water shrew’s preferred habitat is the slow flowing water of a stream or river. However lakes, ponds, and ditches also serve it well if the general ecology is right and pollution is not present. Water shrews may additionally be found considerable distances away from water when on migration from their native area. They occur throughout the British mainland, with the highest concentrations in the south east.

Water shrews are not rare but are less common than their smaller relatives, and harder to find. You are most likely to see them at this time of year when juveniles migrate across land to establish new territories. Until very recently water shrew was not recorded at all for the Roseland but I was lucky enough to see one, confirming their presence here.

All three species of shrew produce young in late spring and summer. Winter survivors mature by the following spring, when they then breed. Pygmy and common shrews live very short lives at a hectic pace. It is all over in less than twelve months. The larger water shrew can live somewhat longer – up to 19 months in the wild has been recorded.

News in brief:

Wet start to summer disastrous for many birds

While the unexpectedly hot, dry start to spring dried up water sources for breeding amphibians, and prompted early breeding attempts by birds, the ensuing weeks of rain and low temperatures meant widespread nest failures afterwards. Not only were bird food resources suppressed by the cold and wet, the rain left it impossible for nestlings to stay dry and warm. Many of our Cirl buntings and other small passerines certainly did not produce first broods. Many of our herring gulls have not bred successfully this year either, reinforcing the need to upgrade their RSPB conservation status which now stands at red level.

St Anthony peregrines fledged sooner than expected

The Peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) breeding at St Anthony produced another successful fledging at the start of this July when their two nestlings lept off their ledge almost a week sooner than expected. This is very excting news and shows that not all species (or all parts of foodwebs) are adversely affected by unusual weather patterns.

Minke Whale seen in Gerrans bay

Two men out fishing in Gerrans Bay at the end of July have seen what is believed to be a Minke Whale. The animal was just poking its head out of the water. but judging by the dimensions of it, the physionomy of its blowholes, plus the widespread distribution of minke whale, we think this is the most likely species to be present in this area. Anyone traveling out in Roseland waters, keep an eye out for any cetacean species and let us know what you see!

Things to do for Nature this month in the Roseland

You may have noticed that many birds are not making quite such a song and dance about life as they were a month or two ago. It’s their moulting time, time to catch up on feeding themselves and not nestlings and generally get back in shape for winter. Time to keep out of harm’s way while not so fit and able to avoid confrontation and predation. So as always we can help them by putting out plenty of good quality foods in various feed points. That way they can conserve energy for plumage production and not have to fly too far.

You may have noticed that many birds are not making quite such a song and dance about life as they were a month or two ago. It’s their moulting time, time to catch up on feeding themselves and not nestlings and generally get back in shape for winter. Time to keep out of harm’s way while not so fit and able to avoid confrontation and predation. So as always we can help them by putting out plenty of good quality foods in various feed points. That way they can conserve energy for plumage production and not have to fly too far.

If, like me, you are lucky enough to have a pond then you can look forward to the noisy croaking and singing calls from frogs and toads in springtime, or even watch the courtship dances of newts in the water. If you don’t have a pond in your garden then consider putting one in; even if it’s very small it can make a difference to your garden’s biodiversity. Pond Conservation’s Million Pond Campaign aims to increase the number of ponds with good water quality across the country, to help renew ponds that have been filled in or lost through pollution. You can find out more here.

Butterfly Conservation need your help for the world’s biggest butterfly count. Spend just 15 minutes watching butterflies in any sunny place then submit your sightings online. You don’t need to be an expert! Download the identification chart. Big Butterfly Count runs from 14 July – 5 August 2012. BBS volunteers can also survey butterflies on their square/s for the Wider Countryside Butterfly Survey.

Butterfly Conservation need your help for the world’s biggest butterfly count. Spend just 15 minutes watching butterflies in any sunny place then submit your sightings online. You don’t need to be an expert! Download the identification chart. Big Butterfly Count runs from 14 July – 5 August 2012. BBS volunteers can also survey butterflies on their square/s for the Wider Countryside Butterfly Survey.

References

First Nature (2012) Welcome to the ampibian pond. [Online]. Available here

The Mammal Society (2012) Fact Sheet: The Water Shrew (Neomys fodiens) [Online]. Available here.

Abyes, C. & Sargent, G. (1997) Investigation into survey techniques for recording water shrews (Neomys fodiens). Mammal Society Research Report No. 1.

Churchfield, S. (1988) Shrews of the British Isles. Aylesbury. Shire Publications Ltd.

Churchfield, S. (1990) The Natural History of Shrews. London. Christopher Helm Ltd.

Sarah Vandome