So that’s Christmas done and dusted for another year! The bees were out doing their Christmas shopping on Christmas eve

(they always leave things until the last minute – can’t think where they get that from!) but have stayed indoors since then. The rain and the icy NW wind persuaded them that it was not worth the risk of going out – and after our stroll on Carne Beach on  Boxing Day, I can totally understand that! It was bitter, yet several swimmers were going into the water for their seasonal dip. I think they’re as mad for doing that as they possibly think I am for exposing myself to bees, but at least I get some reward for my endeavours!

Boxing Day, I can totally understand that! It was bitter, yet several swimmers were going into the water for their seasonal dip. I think they’re as mad for doing that as they possibly think I am for exposing myself to bees, but at least I get some reward for my endeavours!

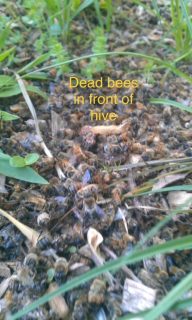

One of my beekeeping students contacted me before Christmas saying she had found lots of dead bees outside her hive – “What was going on?”.

One of my beekeeping students contacted me before Christmas saying she had found lots of dead bees outside her hive – “What was going on?”.

She was gutted, blaming herself for their demise, but it was nothing to do with what she had or hadn’t done. It was the effect of the mild weather followed so suddenly by those icily cold few days – the bees had been caught short whilst out foraging, had managed to get back to their hive – just – but had not been able to warm up again (hypothermia). They then died inside the hive and the remaining bees had cleared them out (as far as they dared in the cold weather) and dumped them over the edge of the alighting board, to be discovered by their keeper on the ground in front of the hive. There are plenty of bees left in the colony to see it through but it’s still a very worrying sight for any beekeeper.

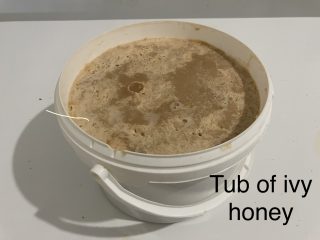

All the bees’ surplus ivy honey has now been removed and they are now relying on what they’ve stored in their brood box, and the fondant I’ve place over their feeder hole, to sustain themselves until the Spring weather arrives. All I have to do now is cut out the combs from the frames, melt them down and when the melt is cooled, separate the wax disc that will be floating on top. I normally then transfer the honey to tubs that I will fill bottles from whenever needed, rather than bottling straight away. This gives the enzymes more time to continue working which improves the flavour of the honey

A lot of beekeepers do not like ivy honey because of it setting so rock hard in the combs. They maintain that the bees cannot access it because of its hardness, yet the bees have survived on such winter forage for over a million years. I think it is more likely that they do not like the taste, as it is somewhat medicinal in nature compared with runny, blossom honey and is, perhaps, an acquired taste. I remember in my very early days going to a beekeeping apiary meeting and afterwards being treated to splits with honey and a cup of tea. Believe it or not, that was the first time that I remember tasting honey and I found it cloyingly sweet, far too sweet for my taste. I then started wondering what I was going to do with all the honey my future bees were going to produce and that I would not like! I am pleased to say that I no longer have that problem, partly due to the fact that the honey that my bees produce is not as cloyingly sweet as my fellow beekeeper’s and partly because I actually prefer the “medicinal” taste of their ivy honey. Each unto his own, I guess.

Honey bee workers collect pollen and nectar from a variety of flowering plants to use as a food source. They typically forage from up to 1-2 miles away from the hive, though sometimes they can travel even further, even up to 10 miles away, though then only in an emergency. However, much of the modern landscape consists of agricultural fields, which limits the foraging options for honey bees in these areas.

Furthermore, when crops decline at summer’s end, honey bee populations in commercially farmed crop-heavy areas, such as rape or soybean, experience massive losses, posing the question of how agricultural landscapes impact the type of food the honey bees bring in, and if this food then affects the queen’s production of eggs. Recent American research explored these questions in a new paper published in Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems.

The study involved two components. The first involved placing honey bee colonies across differing agricultural vs wildflower prairie landscapes, and measuring the species and amount of pollen collected, as well as the number of eggs laid by the queen. The researchers found that the quantity of pollen didn’t vary based on crop vs prairie location, but that the species of pollen did, the main difference being that honey bees near prairie collected more evening primrose pollen than honey bees near crop fields.

Additionally, queens from colonies placed closer to prairie laid more eggs than those near crop fields, particularly in late summer, when crop availability decreases. This result did vary a bit year by year, because field experiments with honey bees have so many variables to account for. It’s very complicated in the field to tease apart these differences, as it could be crop, pesticides, the randomness in the colonies…it could be all kinds of interactions. My personal (unscientific) feeling is that the queen’s laying drops off because she knows the bees are busy foraging for a scarce forage source and don’t have as much time or food to tend a large brood nest. But what do I know?!

For the second part of the study, the researchers used small microcolony honey bee boxes to test the question of nutritional impacts on egg laying in a controlled laboratory setting, the first study to replicate a field experiment in this way.

Collection of August pollen mass did not differ by landscape treatment in any year. The colonies were fed one of three treatment diets that mimicked the dietary mixtures found in the field component of the study: crop mixture, prairie mixture, or 100% evening primrose, which was added to see if its nutritional value was the reason the honey bees favored it as a pollen source in the field. The researchers then counted the number of eggs the queen of each colony had laid every day.

In line with what was found in the field, queens laid more eggs under the prairie diet compared to those under the crop or primrose diet. The results from both the field and lab components of the study suggest that honey bee colonies do better when given a diverse diet, as would be found in a field of prairie flowers, compared to a less diverse diet of crops. The results indicate that it’s the quality of the pollen that matters more than the quantity that they’re bringing in. There are specific pollens, like evening primrose, that when mixed in can be more nutritious overall. However, in the lab, primrose did not provide enough nutrition by itself to change the queen’s fecundity. So, the take home here is that the honey bees need a diverse diet.

So, what can farmers and/or beekeepers do to help honey bees through the shortage of food in August? The researchers explained that prairie strips, which are already being implemented by farmers for other reasons, come with the added benefit of helping the honey bees. By placing strips of native prairie plants around water ways and farm edges, farmers reduce erosion and water loss on their farms, and also provide an additional food source for honey bees. And with laboratory studies like this, researchers can give better suggestions on what types of prairie plants to provide on the strips.

This is a new way of thinking about what is measured in these colonies. Being able to see that when you have this or that in your landscape, your queens are more productive, is really valuable.

The researchers plan for the next research steps will focus on pesticide exposure and interactions with pollen on queen fecundity. Pesticides present a large problem for bees in general, but the specific effects of pesticides can be hard to study in such variable field settings.

This laboratory system will allow manipulative experiments which will look very finely at what’s going on in the honey bee colonies.

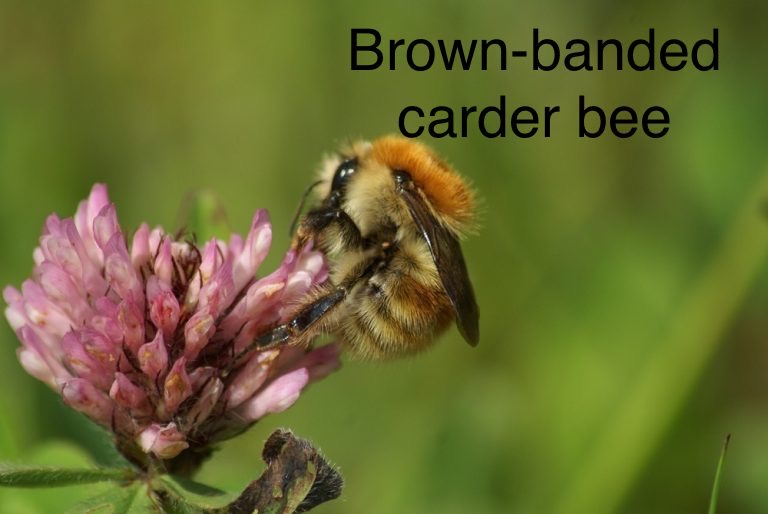

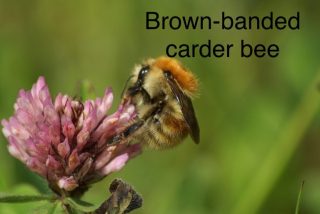

On an unrelated topic, one of the UK’s most threatened bumblebees has been rediscovered at a site in Devon.

On an unrelated topic, one of the UK’s most threatened bumblebees has been rediscovered at a site in Devon.

The brown-banded carder bee population has declined due to habitat loss as it requires open flower-rich grasslands where wildflowers thrive, says charity Buglife. In 2022, it was rediscovered at Prawle Point, in the South Hams, the first time since 1978.

Conservationists said it was a “fantastic and highly important find”. A project called Life on the Edge, which is a multi-partner scheme, aims to restore populations of some of the UK’s rarest invertebrates and plants living along the south Devon coast between Berry Head and Wembury, including the last known colony of the six-banded nomad bee. The project reports: “This recent discovery as part of a wider rare invertebrate survey on the south Devon coast, is our headline news of the summer. We are delighted that a lost species has been rediscovered at Prawle Point for the first time since 1978. This is a fantastic and highly important find. It shows that our Life on the Edge project is already delivering, thereby boosting our knowledge of these special insects and we look forward to more finds as the project develops.”

The species has also recently been rediscovered in the north of the county.

The project is currently in its development phase and has been funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Devon Environment Foundation and Milkywire.

If successful in securing its second round of funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the project will run from April 2024 until 2029.

So, good news for the bees! A lot of interest is being shown in the decline of our insect populations, so it’s good to know there are on-going projects looking into various aspects of these so-important species. Without the bees we are doomed – literally – so let’s all do our bit as well by planting and sowing bee-friendly plants and flowers, as opposed to the showy, blousy cultivars that can be found in so many nurseries and garden centres.

A Happy and Healthy New Year to you all and here’s hoping for peace on our planet. See you next year.

Colin Rees 07939 971104 01872 501313 colinbeeman@aol.com