Well, what a month October has been! Rain, wind, more rain – yet more wind. It’s no wonder the bees are confused. I was called out to a swarm this month, on a local farm, where bees were found inside a pile of silage bales. I’ve had this happen before, so I knew what to expect – as far as the bees were concerned anyway.

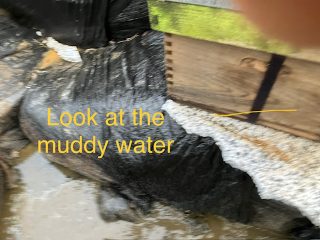

When I arrived at the farm I could see a pile of silage bales further along the track I’d just driven along outside the farm house. I was about to continue to drive towards these when I met the farmer’s son who said no, the bales with the bess were across the other side of the farmyard and he advised me to park more or less where I was. We then proceeded to walk towards the bales – or should I say squelch! The farmyard leading up to the bales was knee deep in mud and farmyard manure. I dread to think what would have happened if I had slipped and falled, as slip I did indeed do! Anyway, we reached the bales and there they were in all their glory, covered temporarily in an old coat and some polystyrene sheets to give at least some protection against the elements.

Silage bales can generate a large amount of heat in their early stages after baling and the swarm had obviously arrived round about May/June time and having found a lovely, warm sheltered spot to make their home, had built their comb deep inside as if it were in their forever home.

Unfortunately for them, when an outer bale was removed earlier this month, their “roof” (to which the upper part of the combs were attached) was taken away, exposing their nest to the elements and causing the remaining combs to splay sideways like the pages of an open book. It was during a spell of wet weather, so these combs and some of the brood were exposed to the rain and cold, and when I arrived at the scene, the bees were clustering tightly around the lower parts of the combs to keep themselves and their brood warm, if not dry. In fact, they were so cold and wet that they took no notice of my intervention and just remained either on the comb or in their cluster, perhaps understanding what I was trying to do for them.

The combs were attached together at their base but luckily not to the silage bales, so I was able to lift the combs as a single unit and place them on a hive floor that I had brought with me. I then placed a brood box over the entirety of the combs (which luckily did not extend beyond the walls of the brood box), put a crown-board on top, a sheet of polystyrene on top of that then finally a roof.

All of this without a single sting or intervention from the bees on what was a very windy evening. Amazing really. About four days later I needed to return to take the bees away so I phoned the farmer first to ask if he could take me to the hive on the back of a trailer. I did not want to end up slipping and falling whilst carrying a hive of bees! He totally understood but suggested a tractor and shovel would be better transport!

I’m up for most things so when I arrived on the night, into the shovel I climbed with my hive straps and off we went through the quagmire. I closed the hive entrance with foam, strapped it up so it wouldn’t come apart, and placed it in the shovel. I clambered back in as well (nearly leaving a wellington boot behind in the mud where the bales were!)

and straddling the brood box so I could steady it with my knees, off we went. It was certainly the right decision not to try carrying it as we’d had quite a bit of rain in the interim, and conditions under foot were a lot worse than on my first visit.

Having retrieved the bees and put them in the car, I drove home, placed them on the stand that was to be their new home, and removed the foam from the box entrance. Job done! No calamities. No aggressive bees. It’s easy-peasy being a beekeeper!.

The next evening, I put a block of fondant over the feed-hole in the crown-board and even by today, though they have eaten some of it, they have not taken a lot. This tells me they have been foraging (as I could see on the good days) and were being quite self-sufficient.

That means they most likely had a laying queen which was quite something considering what they’ve been through. All I have to do now is to get them through the winter, making sure they are never short of fondant.

Back to honey! A pound jar of very fresh wildflower honey will taste like a sunny summer day all year long.

During the honey flow period, many established colonies make more honey than they need.

Honey begins as nectar from flowers. Worker bees collect nectar and pollen for food. The nectar that isn’t immediately consumed is stored in the bees’ honey stomach and taken back to the hive. Honey bees’ salivary enzymes and proteins break down the nectar’s complex sucrose and starches into simple, more quickly digested sugars — glucose and fructose.

Because wild yeasts and bacteria can easily live on nectar, robbing its nutrients, honey bees reduce the nectar’s water content in two astonishing ways. First, they repeatedly regurgitate the nectar into their mandibles to create bubbles that provide a large surface area for water to evaporate. Second, after storing the partially dehydrated solution in open wax cells, groups of workers will constantly fan their wings, producing heat and airflow to reduce the water content even further. After the solution lowers to a water content of 18% to 15.5%, bees cap the cells with wax.

The nectar is now beyond the saturation point of water. This means there is far more sugar dissolved in what little water remains than ever could be dissolved in an equivalent volume of water.

For example, it’s impossible to dissolve one cup of sugar in seven teaspoons of water. This is honey.

Honey’s supersaturation of sugar is incredibly stable on molecular and chemical levels. Yeasts and bacteria are prevented from living on honey while in the capped cells, which ensures a very fresh and untainted food source.

The type of honey a colony produces depends entirely on the nectar’s primary source. Wildflower, the most abundant type of honey, is a combination of all of the thousands of different flowers from which the bees forage. Wildflower honey is typically light to dark amber in color and can have a very complex, multi-faceted taste.

Other local nectar sources, such as hawthorn and blackthorn, produce a much lighter-tasting, grassy-golden honey. Regardless of what the label says, no one knows what other flowers’ nectars are present without microscopically identifying the unique pollen cells in honey. Bees don’t discriminate.

At retail, honey is offered in many forms, but it’s either raw or processed. Most commercially produced honey is pasteurized, which ensures bacterial decontamination that may occur after uncapping the cells for extraction and the packaging process. Raising the temperature of honey above 104F also diminishes many of the unique qualities of honey. If you’ve ever had milk fresh from the cow, you’ll understand. Commercial honey may also contain additives like high-fructose corn syrup or artificial coloring, which is why I always say, if you want pure honey then you have to buy straight from a beekeeper.

I’ll continue this discussion about honey in future blogs but it does no harm to re-iterate the above.

Meanwhile, Asian Hornets continue their incursion into the UK – we now have a total of 62 Asian Hornet nests found in 48 locations, most of them on the East coast in Kent, but they have been sighted in Devon so we can’t relax just because we live in Cornwall.

Now that the leaves have gone or are going from the trees, the Asian Hornets’ nests will be more readily visible, so stop looking at your phones and look up into the trees occasionally and if anything suspicious is seen, contact Asian Hornet Watch through the app, downloadable to your phone for free. Beekeepers will be forever grateful!

Colin Rees 07939 971104 01872 501313 colinbeeman@aol.com