What’s the difference between blossom honey and Ivy honey? What are the different kinds of honey? And why is honey good for us? As he prepares his bees for winter bee keeper Colin Rees explains all this and why the honey he is harvesting this year isn’t quite what he expected.

It’s been a busy month, dodging the showers, removing full supers of honey, getting the bees ready for winter and selling off some of my hives. I am having to down-size – I have too many colonies! (according to my wife!!). I was really pleased with the weight of my supers as I cleared the bees off the combs and took the honey home for processing. Beautiful, white wax cappings on completely filled frames of honeycomb.

What more could a beekeeper want?

Everything was fine until I started to uncap the combs.

It was then I realised that the summer honey the bees had brought in that I was hoping to extract – lovely, runny honey that we all love – had been eaten by the bees during the terrible weather we had in July and had been replaced by IVY honey!

Ivy honey is different from blossom honey in that it sets rapidly in the comb and cannot be extracted in the normal way. I therefore had to change tack and set about cutting the combs of ivy honey out of the frames.

The resulting block of honey is then cut into roughly 1 inch cubes prior to being placed in a sealed honey bucket prior to melting down. This is the only way to retrieve the honey. The contents of the bucket are warmed to melting point and then allowed to cool, at which point the wax floats to the surface and solidifies as a disc which can be removed to leave the ivy honey behind. I then put this in sealed tubs whilst it is runny where, after three or four days, it will set once more after the enzymes have done their job. When I need to bottle the honey I will warm it again until it is soft and almost runny and pour it into jars. Job done!

Going back to the frame from which the set honey had been cut, I then carve the top half inch of comb, which was left after cutting out the block, into a V shape. This will give the bees a starting point from which to draw their natural comb in the Spring – much better than plain wax foundation.

The benefits of honey

Whilst on the subject of honey (we’re never far from that subject in beekeeping!), honey’s benefits have been touted since antiquity – and it turns out the ancient Greeks and Romans were onto something – honey really can hit the sweet spot when it comes to our health.

Though honey — a sweet, sticky liquid made by honeybees from flower nectar — is technically a sugar, it’s also really rich in a lot of different bioactive substances,. Those include a range of good-for-you minerals, probiotics, enzymes, antioxidants and other phytochemicals.

There are four common types of honey. Raw honey is defined as “honey as it exists in the beehive or as obtained by extraction, settling or straining without adding heat.” Manuka honey, produced from the flowers of manuka trees, is known for its unique antibacterial properties, attributed to a compound called methylglyoxal. Organic honey is produced without the use of synthetic chemicals, pesticides or GMOs, and locally produced honey has been reported to provide relief from seasonal allergies to local pollen (hay fever), though scientific evidence to support that claim is limited.

Honey can be substituted for sugar in recipes, but remember, it has a distinctive flavour (which varies depending on the source flowers), it’s sweeter than sugar (the general rule of thumb is to use ¾ to 1 cup of honey for every 1 cup of sugar), it’s a liquid, so you may need to cut back on other liquids or slightly increase the dry ingredients in a recipe, and it browns more quickly than sugar (so reduce the oven temperature by 25°F).

But whatever way you use honey — in a recipe or as a condiment — always keep in mind that it is a sweetener. Honey is a supersaturated sugar solution, and we should limit added sugars of all types. Still, if you’re looking for a sweetener that has more to offer, honey is fantastic. Here are six reasons why.

- Honey doesn’t raise your blood sugar as rapidly as white sugar

Honey is metabolised differently from white sugar and produces less of a sugar spike. Research suggests that honey may enhance insulin sensitivity and may support the pancreas, the organ that produces insulin. A 2018 review of preliminary studies points to honey’s “hypoglycemic effect” and use as a novel antidiabetic agent that might be of potential significance for the management of diabetes and its complications. A 2022 study out of the University of Toronto found that honey improves important measures of cardiometabolic health, including blood sugar, cholesterol and triglyceride levels, especially if the honey is raw and from a single source.

Honey can help with wound or burn therapy

Honey has been used for wound healing for centuries, and certain types of honey, like medical-grade honey, have shown potential in wound management due to their antimicrobial properties and ability to promote healing. There’s actually a lot of evidence that using honey during oral cancer radiation treatment helps to prevent some of the nasty side effects of mucositis or inflammation of the mouth.

How does it work? Research suggests that honey prevents or controls the growth of bacteria on the wound, helps to slough off dead tissue and microorganisms, and transports oxygen and nutrients into a wound for quicker healing.

Honey is rich in polyphenols, including flavonoids. Why does that matter? Because those two substances have both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, meaning they protect our bodies against oxidative stress, which can manifest as cancer, heart disease or other diseases. But the polyphenols in honeys can vary significantly, depending on the type of honey and its floral source.

- Honey can be an effective cough suppressant

A 2020 meta-analysis found that honey provides a widely available and inexpensive alternative to antibiotics in controlling cough frequency and severity, though it concluded that further studies were needed. It is believed that honey’s thick texture and possible antioxidant and antimicrobial properties may provide relief for cough symptoms, though honey should never be given to infants under 1 year of age due to a risk of botulism.

- Honey may provide antidepressant or anti-anxiety benefits.

Research suggests that polyphenol compounds in honey such as apigenin, caffeic acid, chrysin, ellagic acid and quercetin support a healthy nervous system, which may enhance memory and support mood. Though more study is needed, a 2014 review of research says that one established nootropic (or cognitive-enhancing) property of honey is that it assists the building and development of the entire central nervous system, particularly among newborn babies and preschool-age children, which leads to the improvement of memory and growth, a reduction of anxiety, and the enhancement of intellectual performance later in life, (though I don’t know how that fits in with the warning not to feed honey to infants under 12 months of age!).

- Honey may support a healthy gut

Early research indicates that honey has an extra-special ability to support a healthy gut microbiome because it contains both probiotics, or good bacteria, and prebiotic properties, which help good bacteria thrive, though the evidence is limited. A 2022 paper funded by the National Institute of Health, Malaysia, concluded that “honey bees and honey, which have the potential to be good sources of probiotics and prebiotics, need to be given greater attention and more in-depth research so they can be taken to the next level.”

Bottom line – honey is good for you if it is raw, natural and unprocessed. Nothing new there then!

How to encourage bees into your garden

We can do a lot to help the bees throughout the year, especially during times of natural dearth (the ”June gap”). If you want to create your own pollinator garden for bees to forage in, then you should;

- Opt for native plants or naturalistic perennials.

- Choose plants of varying colours, shapes and bloom times so you can support a variety of pollinators throughout the season.

- Avoid double-flowered varieties (those with extra petals) or plants that look drastically different from their wild relatives.

- Avoid pesticides.

- Leave areas in your garden that can serve as nesting habitats, such as patches of bare soil, brush, twigs or woody stems, where many native pollinators make their homes.

Which plants are right for you depends on your location and climate, so ask your local nursery for advice — or simply walk through a nursery and notice which plants seem to attract pollinators.

The Asian Hornet reaches Plymouth

Finally, a word (or two!) about Asian Hornets. This year there have been 58 sightings of this invasive pest at 46 locations in the UK, the nearest to us being in Plymouth – a bit too close to home!. So far, all the nests associated with the sightings are believed to have been found and destroyed but it only takes one queen to evade these measures or to have left the nest to hibernate before the nest was destroyed and we are in deep trouble.

It is likely the Asian hornet has become established in the UK, conservationists fear, as a record number of nests have been found. There has been a sharp rise in sightings of the invasive species in the UK this year; the previous two years only had two sightings each.

The vast majority of the sightings have been in Kent and some experts are concerned the species may have established itself there. The government’s strategy is to locate and kill every hornet and destroy all nests to prevent them from staying over winter and multiplying. Once they are established, it will be almost impossible to get rid of them.

The bumblebee conservation expert Dave Goulson, a professor of biology at the University of Sussex, said he feared it was likely the hornets had become established in Kent

He told the Guardian: “It is a bit too early to say for sure but the situation looks ominous. If even one nest evades detection and reproduces it will then probably become impossible to prevent them establishing.”

Goulson said they would likely remain for good once established. “I think it is inevitable that they will eventually establish in the UK, and once here it is hard to see how they could be eliminated.” This would be terrible news for native bees, which the hornets dismember and eat. They have thrived in France, where they have caused concern with the number of insects they have killed. They sit outside honeybee hives and capture bees as they enter and exit. They chop up the smaller insects and feed their thoraxes to their young. Goulson added: “The arrival of Asian hornets would provide a significant new threat to insect populations that are already much reduced due to the many other pressures they face, such as habitat loss, pesticide use and so on.”

Matt Shardlow, the chief executive of the insect charity Buglife, agreed with Goulson, saying: “With four new Asian hornet nests being detected in the last week and a strong cluster in coastal Kent it seems likely that the species has colonised England. The Asian hornet is a risk to biodiversity; in particular it can hunt large numbers of wild solitary bee species.

“It is too early to give up on control efforts. Removing nests has probably managed to slow its colonisation, and the abundance of different wasps can be strongly influenced by weather, so we can still hope that eradication efforts, perhaps with some lucky weather, might nip this colonisation in the bud.”

The British Beekeepers Association trustee Julie Coleman, who lives in Kent, said hornets could have already overwintered in the area. “The fact that we seem to have a cluster around the coast in Kent, also Dorset, Plymouth, Weymouth and Hampshire, makes me think they are coming across on the wind. And there could have been an overwintered nest in Kent which has sent out hibernating queens in the autumn.”

Asian hornets first came to Europe in 2004 when they were spotted in France, and it is thought they were accidentally transported in cargo from Asia. They rapidly spread across western Europe and have crossed the Channel to Britain, probably also in cargo, but they can also come on the wind or under their own steam.

Experts recently warned that lax post-Brexit trade rules could be helping the hornets colonise Britain. The EU has banned the import of soil in pot plants from the UK since Brexit, partly because invasive species such as the Asian hornet can travel undetected in soil. The UK has not put reciprocal bans in place, however, meaning damaging species from the continent could be transported in soil.

Asian hornets are smaller than native hornets and can be identified by their orange faces, yellow-tipped legs and darker abdomens.

Nicola Spence, the chief plant and bee health officer at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, said: “Evidence from previous years suggested that all 13 Asian hornet nests found in the UK between 2016 and 2022 were separate incursions and there is nothing to suggest that Asian hornets are established in the UK. We have not seen any evidence which demonstrates that Asian hornets discovered in Kent this year were produced by queens that overwintered. We plan to do further detailed analysis over winter to assess tevent that the Asian Hornet has his”.

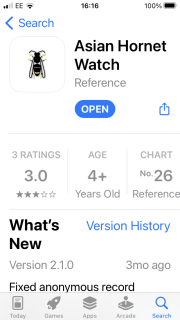

So the jury is still out. In the hope that the Asian Hornet has not yet become established, we need to carry on looking for potential signs of its presence. Look up in the trees for signs of nests and if you see a strange or unfamiliar insect, try and trap it until identification can be made. It can always be released if it is a harmless native, or put in the freezer until identification is confirmed after you have reported it via the Asian Hornet Watch app downloadable to your mobile phone.

On that cheerful note, I will finish this somewhat longer than usual blog and like you, will keep my eyes peeled for any strange sightings.

Colin Rees 07939 971104 01872 501313 colinbeeman@aol.com