Lead Kindly Light

Sometimes at night, with the right conditions, from my bedroom window I can see the loom of the Lizard light as it swings, reflected in the sky. I know it is Lizard and not St Anthony by counting the sequence of flashes. Each lighthouse is given a distinctive sequence of on/off so you can tell one from the other. This also applies to lightships, buoys and lights at harbour entrances. True there are not enough possible variations to cover every light in the world but there are no repeats within a radius of several hundred miles. The Powers That Be think it reasonable that the captain of a ship should, at least, know if he is off Lands End or the Orkney Islands.

Sometimes at night, with the right conditions, from my bedroom window I can see the loom of the Lizard light as it swings, reflected in the sky. I know it is Lizard and not St Anthony by counting the sequence of flashes. Each lighthouse is given a distinctive sequence of on/off so you can tell one from the other. This also applies to lightships, buoys and lights at harbour entrances. True there are not enough possible variations to cover every light in the world but there are no repeats within a radius of several hundred miles. The Powers That Be think it reasonable that the captain of a ship should, at least, know if he is off Lands End or the Orkney Islands.

It is quite a complicated system. There are three basic types of flash. Occulting where the duration of light is longer than the dark, Isophase where the periods of light and dark are equal and Flashing where the duration of light is shorter that the dark. There are even subdivisions of these three such as Quick and Very Quick. In fact a look at Reeds Nautical Almanac shows that there are twenty possible variations – before you even start on colour changes! True the only colour change you are likely to see are red and green but theoretically there are others.

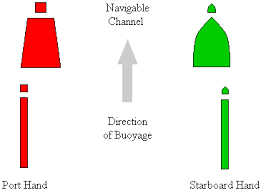

Around the British Isles the only colours I have ever seen are red and green, often at harbour entrances, and then marking the safe channel with buoys. As you go in you leave red to port and green to starboard – unless you are in America or the Pacific where, of course, they work the other way round.

Many lighthouses have a red sector and this covers the hazards they mark so that, if a captain sees the light change from white to red he knows that he is running down the dangers and must move back so that the light changes to white. This does not work with lightships or buoys as they are anchored and swing about with the tide. Our nearest lighthouse with a red sector is Eddystone where the red covers a small group of off lying rocks to the northwest.

Many lighthouses have a red sector and this covers the hazards they mark so that, if a captain sees the light change from white to red he knows that he is running down the dangers and must move back so that the light changes to white. This does not work with lightships or buoys as they are anchored and swing about with the tide. Our nearest lighthouse with a red sector is Eddystone where the red covers a small group of off lying rocks to the northwest.

I often wonder at the ingenuity and persistence of the men who built lighthouses. Building on land was not too difficult though it must have been hazardous when you see how some cling to the cliff tops. They made mistakes sometimes. There are several where the light was built high on the cliff only to realise that it could become shrouded in frequent fog so they had to start again lower down or in the sea itself. Beachy Head was one of these.

The first light, Belle Tout, was built in 1828 but by 1900 it was abandoned, partly because the cliff top was eroding and partly because it was frequently shrouded in fog. Its replacement was built in the sea at the foot of the cliff involving the construction of a coffer dam to protect the building work and a cable system from the cliff top to carry material to the site. 3660 tons of Cornish granite went down the cableway!

How do you manage though if you do not have a handy cliff nearby from which you can lower materials? One of the most daunting was Wolf Rock half way between Penzance and the Scilly Isles, a single pinnacle of rock completely exposed to the Atlantic. The scene of many shipwrecks, a man called Henry Smith got permission to build a lighthouse in 1791. The task proved too much for him and he settled for an unlit wrought iron tower as a day mark. The Atlantic laughed – it did not survive the winter.

How do you manage though if you do not have a handy cliff nearby from which you can lower materials? One of the most daunting was Wolf Rock half way between Penzance and the Scilly Isles, a single pinnacle of rock completely exposed to the Atlantic. The scene of many shipwrecks, a man called Henry Smith got permission to build a lighthouse in 1791. The task proved too much for him and he settled for an unlit wrought iron tower as a day mark. The Atlantic laughed – it did not survive the winter.

Then, over a period of five years, James Walker built a more substantial tower of iron, recording that over the five year period from 1836-40 there were only 300 hours when conditions were suitable for work. That works out at about 40 days over five years! Bits of that tower still remain. But Walker was not satisfied and went back in 1861 and started on a stone tower. The tenacity of these men! By the end of 1864 they had only managed to lay 37 stones though a landing stage and crane had been completed. The tower was finished in 1869 and is still there – the first in the world to be fitted with a helipad to make maintenance easier.

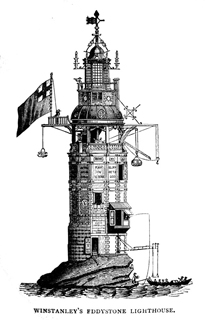

The Eddystone has seen four lighthouses. Winstanley built the first completing it in 1698. While it was being built a French privateer attacked, destroyed the work and took him prisoner. Louis XIV was not pleased and commented, ‘France is at war with England, not with humanity’. The wooden tower survived till the Great Storm of 1703 when it disappeared, taking with it Winstanley and five other men with him on the lighthouse.

The Eddystone has seen four lighthouses. Winstanley built the first completing it in 1698. While it was being built a French privateer attacked, destroyed the work and took him prisoner. Louis XIV was not pleased and commented, ‘France is at war with England, not with humanity’. The wooden tower survived till the Great Storm of 1703 when it disappeared, taking with it Winstanley and five other men with him on the lighthouse.

Next came Rudyard’s light. This lasted nearly fifty years until in 1755 the top of the lantern caught fire. The three keepers were driven out on to the rock from which they were rescued by a passing boat. One keeper, Henry Hall, died from ingesting molten lead – not a nice way to go. He was, however, 94 at the time so one must wonder what he was doing still working as a lighthouse keeper – hardly a gentle task. A post mortem must have been performed as they recovered a piece of lead from the body and this is now in a collection at the National Museum of Scotland! How did it get there?

Then came Smeaton’s famous lighthouse, 1756 to 1857, when it was removed and re-erected on the Hoe. Its replacement was lit in 1882 and is still in use.

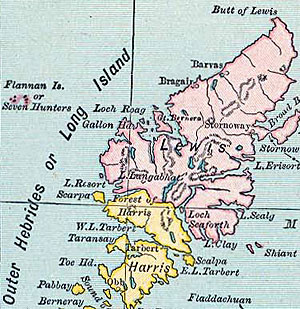

Lighthouses are always a story of engineering skill and great endurance. One, however, is the scene of one of the great mysteries of our time. Twenty miles west of the Isle of Lewis lie the Flannan Isles, a group of rocks also known as the Severn Hunters. A lighthouse was built on the largest island and completed in 1899. It was manned by three lighthouse keepers and there was no radio communication between the lighthouse and the Isle of Lewis. A local gamekeeper on Lewis was paid the sum of £8 per annum to keep a watch on the light and report any failures to the Lighthouse Board. Distance was such that he needed good visibility to be effective.

Lighthouses are always a story of engineering skill and great endurance. One, however, is the scene of one of the great mysteries of our time. Twenty miles west of the Isle of Lewis lie the Flannan Isles, a group of rocks also known as the Severn Hunters. A lighthouse was built on the largest island and completed in 1899. It was manned by three lighthouse keepers and there was no radio communication between the lighthouse and the Isle of Lewis. A local gamekeeper on Lewis was paid the sum of £8 per annum to keep a watch on the light and report any failures to the Lighthouse Board. Distance was such that he needed good visibility to be effective.

On 15th December, 1900, the ship Archtor was on passage round the north of Scotland when she reported that the light on the Islands was not lit. It was arranged that the Lighthouse tender Hesperus would go out to the island. The normal monthly visit of the tender was due in any case but adverse weather kept it in port until 26th December. On arrival at the Islands the

Hesperus crew were surprised that no one from the lighthouse was on the landing stage to greet them and no preparations were made to receive provisions. The landing stage was deserted. The Hesperus put men ashore and they made their way to the lighthouse . They found it deserted and there was no sign of the three keepers anywhere on the island. Two sets of oilskins were missing from the lighthouse but one set still hung on its hook. The log book was correctly made up to date to 15th December and the light was trimmed and made ready. The living quarters were in order, the washing up done. Apart from the missing men nothing seemed amiss.

There are many fanciful suggestions as to what happened and the story has attracted various embellishments. It is better to rely on the official investigation by the Northern Lighthouse Board. This noted that there was severe damage to a storage box 110ft above the crane on the jetty and that ropes were in disarray. There was evidence of wave damage high on the path down to the jetty. It concluded that two of the men had gone down to secure the box before an impending storm.

There are many fanciful suggestions as to what happened and the story has attracted various embellishments. It is better to rely on the official investigation by the Northern Lighthouse Board. This noted that there was severe damage to a storage box 110ft above the crane on the jetty and that ropes were in disarray. There was evidence of wave damage high on the path down to the jetty. It concluded that two of the men had gone down to secure the box before an impending storm.

This would be in compliance with the Board’s directive that there must always be one man left in the lighthouse. They then concluded that an immense wave had come in and washed the men away. The third keeper, seeing their plight and believing he could help, had rushed coatless to help only to suffer a similar fate. No one will ever really know what happened.

From our Lookout no lighthouse is visible and, in any case, we do not work at night. This does not mean that, when the weather is bad, we are not reminded of the fearsome power of the sea. Sheltered though our bay is a strong south-easterly will see our windows covered in spray. Fortunately these occasions are least likely to produce a ‘casualty situation’. Bad weather keeps people out of the water, apart from the occasional surfer over towards Portscatho. Our watch is most necessary when the sun is out and the paddle boarders, kayakers and swimmers want to see what is around Pednvadan Point. Easy to get round with the wind behind you but hard work getting back. That is what we are there for – to make sure all water users get back safely to dry land.

From our Lookout no lighthouse is visible and, in any case, we do not work at night. This does not mean that, when the weather is bad, we are not reminded of the fearsome power of the sea. Sheltered though our bay is a strong south-easterly will see our windows covered in spray. Fortunately these occasions are least likely to produce a ‘casualty situation’. Bad weather keeps people out of the water, apart from the occasional surfer over towards Portscatho. Our watch is most necessary when the sun is out and the paddle boarders, kayakers and swimmers want to see what is around Pednvadan Point. Easy to get round with the wind behind you but hard work getting back. That is what we are there for – to make sure all water users get back safely to dry land.

Oh, those telephone numbers you can ring to find out more about becoming a volunteer Watch Keeper. Sue on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681.

Pictures courtesy of Wikipedia and Lighthouse Boards