The weather this past month has not been as cold as it was this time last year, so the bees have had the odd day when flying out of the hive to retrieve water or to void their faeces has been feasible. On the really cold days, though (as we experienced about 2 weeks ago), the bees did not even think about flying out of their hives! Had they done so, they would have rapidly chilled and would have fallen to the ground and died, as once their body temperature drops below 7˚C they will perish.

The weather this past month has not been as cold as it was this time last year, so the bees have had the odd day when flying out of the hive to retrieve water or to void their faeces has been feasible. On the really cold days, though (as we experienced about 2 weeks ago), the bees did not even think about flying out of their hives! Had they done so, they would have rapidly chilled and would have fallen to the ground and died, as once their body temperature drops below 7˚C they will perish.

To maintain such a temperature demands rapid movement of the dorsal muscles and wing vibrating, but if this is not enough, they’ve had it! So they sensibly stay huddled very tightly together to maintain a temperature of anything from 20˚C if there is no brood present to 35˚C if there is brood present. Whilst clustered like this, the bees consume very little food, but will live off their body fats built up during the late autumn. This means they can survive for anything up to six months during the winter months, whereas the normal summer life-span of a bee is nearer six weeks!

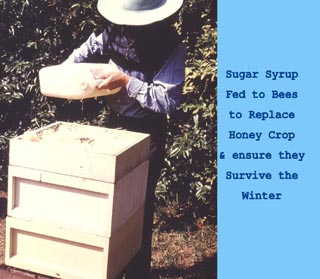

Such a long period of time inside the hive, however, does require the consumption of some hive stores, which is why it is important that the beekeeper ensures there are sufficient to last the whole winter when s/he is preparing the bees during the autumn. Also, this autumn, there was not very much of an ivy flow – doubtless for the same reason it was a poor-ish honey yield during the summer – namely, the water content of the soil was at too low a level for plants to yield nectar. So beekeepers needed to have fed their bees to supplement this meagre ivy flow with sugar syrup or fondant (like a soft icing-sugar). Unfortunately, however well-prepared the hives might be in terms of stored food, when the bees cluster in and around a group of empty cells, those of them on the periphery will have access to food but unless the cluster physically moves en bloc, those in the centre will not.

Such a long period of time inside the hive, however, does require the consumption of some hive stores, which is why it is important that the beekeeper ensures there are sufficient to last the whole winter when s/he is preparing the bees during the autumn. Also, this autumn, there was not very much of an ivy flow – doubtless for the same reason it was a poor-ish honey yield during the summer – namely, the water content of the soil was at too low a level for plants to yield nectar. So beekeepers needed to have fed their bees to supplement this meagre ivy flow with sugar syrup or fondant (like a soft icing-sugar). Unfortunately, however well-prepared the hives might be in terms of stored food, when the bees cluster in and around a group of empty cells, those of them on the periphery will have access to food but unless the cluster physically moves en bloc, those in the centre will not.

Then, when the weather warms up (as it is doing at the moment), the cluster will loosen or even break up altogether and move towards an unopened food source (sealed honey in the comb). If you think about the bees clustering, say, one third of the way into the hive, there will be a third of the frames to one side of the cluster and two thirds of the frames to the other. Should the cluster move towards the one third, there is sometimes a danger that they will gradually move

across those frames and reach a point where there are either no frames left or no food in those on the extremities of the hive. The bees then find themselves isolated from their food source (though there are still plenty of stores on the other side of the hive) and they will die, because, once in cluster they are unable to move across the frames, other than very slowly, to reach those stores, because if they do their body temperature will drop and they will die.

This is the main reason that every winter, round about now, I give the bees a Christmas present of candy or fondant, which is basically sugar that has been dissolved in water to a very high concentration – it looks like royal icing that you find on an iced cake. By placing this candy/fondant over the cluster, the bees then have access to food without having to move across the frames. It’s a kind of “fail-safe”. Apart from that, there is nothing more that can be done to help the bees – but they have been looking after themselves without our “help” for 20 million years, so they should have a reasonable idea of what is needed! Once things start warming up, the beekeeper’s involvement once again will increase but until then, we can only wait and see whilst repairing and preparing equipment for what will be our best honey season yet!

Colin Rees colinbeeman@aol.com 01872 501313