Hubba Hubba, a call that must have echoed around our coast for hundreds of years and one that brought employment and prosperity to our villages. Mevagissey, Gorran Haven, Portloe, Portscatho and St. Mawes, the list could easily carry on up and down the coast. All these small Cornish harbours in years gone by were reliant on Pilchards. It really was a home grown industry. The small silvery fish were caught in large seine nets and brought on shore by the thousands and taken to the so called Pilchard Palaces, which were little more than large lean-too open fronted sheds. Here they were processed and pack into barrels and many of them sent to the Mediterranean markets.

Hubba Hubba, a call that must have echoed around our coast for hundreds of years and one that brought employment and prosperity to our villages. Mevagissey, Gorran Haven, Portloe, Portscatho and St. Mawes, the list could easily carry on up and down the coast. All these small Cornish harbours in years gone by were reliant on Pilchards. It really was a home grown industry. The small silvery fish were caught in large seine nets and brought on shore by the thousands and taken to the so called Pilchard Palaces, which were little more than large lean-too open fronted sheds. Here they were processed and pack into barrels and many of them sent to the Mediterranean markets.

The Pilchard seine net was buoyed along the top and weighted along the bottom. It could be up to a quarter of a mile long and ten fathoms deep and weigh over three tons. The art was to encircle the shoal and draw the net into shallow water where the fish could be scooped out into baskets.

The whole exercise involved scores of people in each place, and sometimes hundreds. Some of the fish were held back for local consumption and of course the money from the sales was all important.

The whole exercise involved scores of people in each place, and sometimes hundreds. Some of the fish were held back for local consumption and of course the money from the sales was all important.

The shoals of fish were eagerly awaited and a sharp eye was kept out for them. Men were stationed on the cliff tops above the bays, and were well trained in spotting the large dark shapes moving through the water. These men known as Huers, could also if necessary direct operations once the boats were launched. When the Huer spotted a shoal he would shout “Hubba Hubba” and the cry would be heard and relayed all around the village. One old fisherman was recorded as saying, ‘Men who had not run more than a few yards since they left school, would run a mile that day. Seining was looked on by people as an extra source of livelihood. But to some it was like foxhunting or a dog after a rabbit. They were mustard at it.’

At Portscatho in 1832, 1,000 barrels of pilchards had been packed and were advertised for sale. The season of 1872 saw 20,000 fish being caught in Gerrans Bay and brought ashore.

At Portscatho in 1832, 1,000 barrels of pilchards had been packed and were advertised for sale. The season of 1872 saw 20,000 fish being caught in Gerrans Bay and brought ashore.

On rare occasions the huge shoals found their way into the Fal and Truro River. 1n 1877 several boat loads were caught just off Tolvern.

The oldest inhabitants at the time could not remember pilchards coming up the river so far. It was thought that they had been driven up by a heavy storm the day before and had passed the St.Mawes Huers unnoticed.

In 1851 while visiting St. Ives the Victorian novelist Wilkie Collins wrote, ‘Here we must prepare ourselves to be bewildered by incessant confusion and noise; for here are assembled all the women and girls in the district, piling up the pilchards on layers of salt, at three-pence an hour; to which remuneration, a glass of brandy and a piece of bread and cheese are hospitably added at every sixth hour, by way of refreshment. It is a service of some little hazard to enter this place at all. There are men rushing out with empty barrows, and men rushing in with full barrows, in almost perpetual succession.’

The processing was all important, and was carried out in much the same way at the different locations, in those halcyon days before health and safety. Mr. Collins recorded that, ‘the labour is thus performed.

The processing was all important, and was carried out in much the same way at the different locations, in those halcyon days before health and safety. Mr. Collins recorded that, ‘the labour is thus performed.

After the stone floor has been swept clean, a thin layer of salt is spread on it, and covered with pilchards laid partly edgewise and close together. Then another layer of salt, smoothed fine with the palm of the hand, is laid over the pilchards; and then more pilchards are placed upon that; and so on until the heap rises to four feet, or more. Nothing can exceed the ease, quickness and regularity with which this is done.

Each woman works on her own small area, without reference to her neighbour; a bucketful of salt and a bucketful of fish being shot out in two little piles under her hands, for her own especial use. All proceed in their labour, however, with such equal diligence and equal skill, that no irregularities appear in the various layers when they are finished—they run as straight and smooth from one end to the other, as if they were constructed by machinery. The heap, when completed looks like a long, solid, neatly-made mass of dirty salt; nothing being now seen of the pilchards but the extreme tips of their noses and tails, just peeping out in rows, up the sides of the pile.’

By far the boom years for the fishery were in the 17 and 1800s. By the early years of the 20th century the huge shoals of fish had started to become few and far between. In 1913 the Cornish Echo reported that the fishermen of St. Mawes were having a very poor season, ‘for some time, the fishermen have been daily eagerly hoping that either the huer, or someone else, would discover a shoal of pilchards sufficiently large for the four seines to shoot, but so far this season no fish have been landed by the seines. The cry Hobba! Hobba! called many of the fishermen in haste from their homes about 4 o’clock on Saturday morning and, on it being reported that a large shoal of pilchards had been seen some distance off the village, the four seiners put out. But the fish which had been seen jumping out of the water, proved to be too far at sea for the seines to be shot.’

By far the boom years for the fishery were in the 17 and 1800s. By the early years of the 20th century the huge shoals of fish had started to become few and far between. In 1913 the Cornish Echo reported that the fishermen of St. Mawes were having a very poor season, ‘for some time, the fishermen have been daily eagerly hoping that either the huer, or someone else, would discover a shoal of pilchards sufficiently large for the four seines to shoot, but so far this season no fish have been landed by the seines. The cry Hobba! Hobba! called many of the fishermen in haste from their homes about 4 o’clock on Saturday morning and, on it being reported that a large shoal of pilchards had been seen some distance off the village, the four seiners put out. But the fish which had been seen jumping out of the water, proved to be too far at sea for the seines to be shot.’

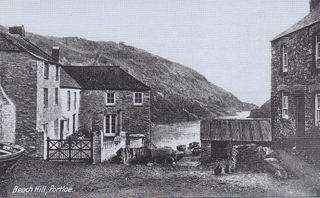

Times were also hard that year for the people of Portloe. The tiny village was almost completely dependent on fishing as can be seen from the large number of boats working out of there. ‘As far as twenty-six drift boats working out from Portloe are concerned, the present pilchard season is stated to be the worst on record. The highest catch this season has been about 2,000 compared with 13,000 last year and the catches have averaged from 500 to 200 fish, against an average of about 5,000 each boat on many nights last year. The price obtained for the few catches landed has been good, having risen from 20 shillings to about 30 shillings per thousand.’

Times were also hard that year for the people of Portloe. The tiny village was almost completely dependent on fishing as can be seen from the large number of boats working out of there. ‘As far as twenty-six drift boats working out from Portloe are concerned, the present pilchard season is stated to be the worst on record. The highest catch this season has been about 2,000 compared with 13,000 last year and the catches have averaged from 500 to 200 fish, against an average of about 5,000 each boat on many nights last year. The price obtained for the few catches landed has been good, having risen from 20 shillings to about 30 shillings per thousand.’

And so the great days of the Cornish pilchard fisheries slowly ground to a halt. In the 1950s I can remember only very rare occasions when my uncle, along with the other fishermen of Portloe, would land a few pilchards. These were eaten with great enjoyment and always looked forward too. In recent years I am glad to say that this humble little fish has achieved a bit of a revival. Many of our seaside restaurants now include them on their menus as Cornish sardines, which seems to have given them a whole new appeal.