Sallie Eden talks to Writer, Professor and fellow Arthur Ransome enthusiast, Alan Kennedy

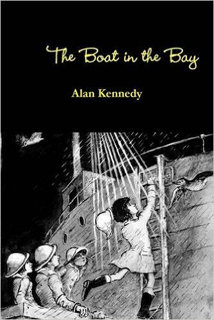

Firstly, a little background: Alan worked in the universities of Melbourne and St Andrews before being appointed Professor of Psychology in Dundee University. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1991, he is an Honorary Member of the Experimental Psychology Society, the only Scottish psychologist to receive that distinction. He has written or edited books on the psychology of language and memory and is the author of four novels and one work of biography. But more important than all of that (I think) is that he is the author of “The Boat in the Bay”, a wonderful homage to Arthur Ransome and a must for all fans of the Swallows and Amazons books.

Firstly, a little background: Alan worked in the universities of Melbourne and St Andrews before being appointed Professor of Psychology in Dundee University. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1991, he is an Honorary Member of the Experimental Psychology Society, the only Scottish psychologist to receive that distinction. He has written or edited books on the psychology of language and memory and is the author of four novels and one work of biography. But more important than all of that (I think) is that he is the author of “The Boat in the Bay”, a wonderful homage to Arthur Ransome and a must for all fans of the Swallows and Amazons books.

As many of Arthur Ransome’s books were written for children (although they are just as enthusiastically read and re-read by adults) I asked Alan about his childhood and his memories of those wonderful stories.

“I was brought up in a little village called Ocker Hill, one of three brothers. My mother was the local schoolteacher. In fact, my earliest memory is of her taking me and my brother to school (her school, not mine). He had a blue hat on – I assume to keep the sun out of his eyes. That was my hat, so much a part of me it rarely came off and I’m told my wails secured its return. I suppose life must have been grim in post-war England, but I had an extremely happy childhood, enjoying an outdoor life with my brothers. Our life also involved a lot of reading. Periodicals, of course – we were allowed The Eagle on condition we read a rather earnest thing called The Children’s Newspaper. We gobbled up the children’s literature of the time – Jennings, Bunter and Just William. Above all, birthday and Christmas presents for three boys ensured a rapid delivery service for virtually everything by Arthur Ransome long before we were out of primary school.”

“I wanted to be a poet, a career choice wisely discouraged by my parents. I compromised by doing a degree in English and then drifting into academic psychology. I wrote about my early days as a novice psychologist in Oscar & Lucy – the Oscar of the title being my first boss, a man whose life story is so incredible it simply had to be written down.”

“I spent most of my life in Dundee, but my research interests meant long periods in Paris and Aix-en-Provence, both of which are markedly unlike Dundee and gave me a taste for the French way of life. My wife and I (and Caesar the dog), now live in rural France, in a house we bought almost by accident. We were at a concert and were chatting to an exotic looking old chap, a kind of diminutive Dali with a very loud voice. I told him we had been house hunting in the region, but were giving up. “Why don’t you buy mine?” he shouted. By the time the musicians were on stage, the whole audience knew every detail and were probably praying we’d get on and buy it so they could listen to the music. And in fact we did. He was a Danish sculptor, and bequeathed us a garden full of monumental pieces far too heavy to move. We live in a bewitching landscape, so quiet you can hear your heart beating.”

What are your interests?

“My professional life was spent immersed in the world of psycholinguistics, a research community divided between ‘speech people’ and ‘reading people’. I’m in the latter group (speech being far too difficult for mere mortals). Skilled reading is the ideal subject for psychological research – a wonderfully intricate process underlying a unique interaction between two minds. Unique because what a reader takes away from a book is not completely determined by what the writer states, or even intends.”

“My professional life was spent immersed in the world of psycholinguistics, a research community divided between ‘speech people’ and ‘reading people’. I’m in the latter group (speech being far too difficult for mere mortals). Skilled reading is the ideal subject for psychological research – a wonderfully intricate process underlying a unique interaction between two minds. Unique because what a reader takes away from a book is not completely determined by what the writer states, or even intends.”

Tell me about your book – what prompted you decide to write it? How long did it take?

“I have to go back a bit. I gave up university life because I wanted to commit myself to creative writing and, to tell the truth, because it was no longer much fun working in a university. My colleagues initially viewed the decision as a kind of lapse of taste – academic dad-dancing, if you like. They are used to it now and a few even read my work. It seemed to me, since I was coming to fiction so late, that if I was ever going to learn how to write a novel, I should start on familiar territory. Now, I happened to know a lot about Arthur Ransome – obviously his fiction for children, but also his books on Poe and Wilde, his translation of Remy de Gourmont and stuff on narrative technique (his obsession).

It sounds rather cold blooded, but I worked quite hard trying to emulate Ransome’s style. I failed, of course, and the book was abandoned. But it wasn’t a wasted effort: it turned out to be a way of discovering a voice of my own. ‘The Boat in the Bay’ was born as a relatively conscious attempt to recover aspects of the life I led with my brothers a lifetime ago. Not through the narration of particular events (although it does have a plot) but by trying to capture something deeper – the magical tone of the imaginative life we (and I guess many others of our generation) led. Once finished, I could hardly wait to get on with the next (called ‘The Broken Bell’). By then I was fascinated by emotional text (high spots, purple prose, whatever you want to call it). In fact, it was seven years and many books later that I went back to ‘The Boat in the Bay’ and with the help of some serious editorial work I tamed it into its present state.”

It seems very accurate period-wise – how did you ensure that?

“The period detail comes from the books I read as a child. Books produced in the forties and fifties (in particular the boarding school genre) often harked back to an earlier – possibly mythical – past.”

What is your target audience?

“Honestly, I dreaded that question (and I’ll avoid saying I write for myself). I think stories that work have to tap into a mythological level of reality. I don’t fully understand how this comes about. So the answer is I don’t have a target audience, but I do have an ambition – I’d like to write a story that works in that way! I claim the enduring appeal of Arthur Ransome’s later fiction lies in the huge mythological resource he deploys in a completely transparent fashion. For example, consider a story about a wise old man who lives under a mountain and possesses a great secret; a story about a magic wand that conjures water from the ground; a story about the quest to make gold in a stolen crucible. Or characters reconciled to their fate by passing through fire – Mozart did something with that idea. One can only speculate as to whether the author of Pigeon Post was consciously aware of all this – the point is such things resonate with children very strongly. And they go on resonating – meaning that adult readers respond afresh to works by recalling their own responses as children.”

Where do you write? In solitude? At home?

“When I was a university researcher I used to work absurdly long hours. I’ve tempered my ways a little, but I still put in five or six hours a day, working at home. Once you’ve started writing it’s a bad idea to give yourself days off, because it takes so long to work your way back in. To state the obvious, writing a novel (even a bad one) is a lonely and time consuming activity. Mind you, once you’ve got that manuscript finished and stacked up on the desk, the process of revision is completely addictive – there’s nothing quite like it.”

What authors do you admire/enjoy? I’m assuming Arthur Ransome is at or near the top of the list!

What authors do you admire/enjoy? I’m assuming Arthur Ransome is at or near the top of the list!

“I do still read Ransome: recently his early work, in particular his essays and translations of French Symbolists. I also read a lot of poetry. I’m currently trying to like Ted Hughes. In fiction, I have always admired Elizabeth Bowen. I recently discovered Eva Trout; her final book is very funny, the humour being entirely linguistic. The last really great novel I read was Stoner by John Williams. It says all you need to know about the good and the bad of academic life. It is extremely sad, but strangely satisfying. Its appearance is also a wonderful modern fairy-tale in its own right: published in 1963 and neglected for fifty years, it was rediscovered in 2013 to huge critical acclaim.”

Have you always wanted to be a writer?

“I searched for myself on Google a while back and found I was described as ‘author’. Since I remember feeling very cheerful for the rest of the day, the answer must be yes.”

Any Cornish connections? Do you sail?

“Both! I learned to sail in Daymer Bay, near Rock. I confess it was so embarrassingly long ago I had quite forgotten. I crewed for three seasons on the Tay for a friend who had a Hurley 24, but the ratio of pleasure to life-threatening frozen misery became so unreasonable I tried to engineer a polite resignation. I was spared the embarrassment – he bought a bigger boat and needed real muscles for the winches. I was sacked.”

What are you planning next?

“I’ve just finished my fifth novel. It’s called ‘Alex’. Elizabeth Bowen’s The Heat of the Day is probably the best evocation of life in war-time England; it prompted me to write a book about life in war-time France. My next novel (in my head it is called ‘Laura’) is bubbling away somewhere but has not spilled any ink as yet.”

Any final thoughts?

“If you want me to say something portentous about reading, the best I can come up with is: remember writing was an invention, not a discovery. We should look after it or risk losing it.” I couldn’t agree more!

Alan Kennedy’s book ‘The Boat in the Bay’ is reviewed in the forthcoming edition of the TARS’ (The Arthur Ransome Society) newsletter.