Another dry month for the bees. After my report last month – the day after, in fact – the nectar flow stopped totally. Bees were hanging around the hive entrances, wondering what to do with themselves. I had, the previous day, removed some supers of honey from two hives and the bees were fine with that. The foragers (who are the ones with developed sting glands) were out of the hive searching for ever-decreasing resources, meaning that I could “steal” the honey they had brought home and stored without any objection from the girls who were at home. Once I had noticed the flow had stopped, however, I desisted from removing any further supers as I knew what the response would be from the now at home foragers.

However, as the month drew on and the bees got used to the fact that there was nothing to forage on, I went back and took a few more supers off the hives, both to harvest the honey crop and to prepare the bees for the ivy flow and the winter ahead. The last thing the bees want in winter is a skyscraper of empty space above their brood nest, losing all the heat they had generated to maintain its temperature at 35°C. There is also a greater possibility that any tall hives will get blown over during winter gales.

Talking about the ivy flow it’s already started here in my home apiary. I noticed last week that there were several bees on the ivy buds, searching for the open flowers.

Unless we get rain soon, though, I am not too optimistic about a sufficient flow for the bees to build up their winter stores. I suspect I will be feeding them early this year. We’ll see. Nature has a myriad of ways to surprise us!

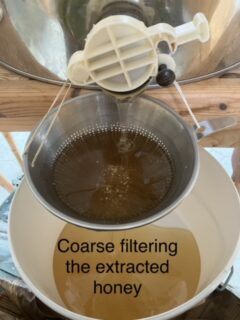

Further to my report last month on honey extraction, I explained how the decapped combs were put in the extractor (or spinner, as it’s sometimes referred to) and then spun to throw the honey out of the combs onto the sidewalls of the extractor.

The honey is coarsely strained into a 30lb tub and stored for a few months, after which time the enzymes have done their work and the honey is in its most mature state and can then be bottled.

I still have a few more supers to remove so will retrieve those later today, having brought some more in yesterday. That, then, should be it for this honey season – apart from finishing the extracting! It looks as if my colonies are strong enough and healthy enough to survive whatever winter might bring, so I am pleased with the way the bees have come on this year. It was a very slow and a very late start but, as ever, the bees have made up for lost time.

A large amount of interest is being shown in the approach to beekeeping that I am a part of, namely “Treatment Free” (TF) beekeeping. I have even been asked to give a talk to one of our beekeeping groups about my approach, so I am hoping that will result in more advocates of the approach. It seems that beekeepers are beginning to realise that if they pour proprietary products into their hives throughout the year to “keep the bees healthy” then the bees will never learn how to keep themselves healthy without our intervention. This, I am sure, will lead to the demise of the honey bee. Look at what is happening in the USA where massive colony losses occur each year. The approach there is to buy in replacements from Australia and New Zealand each year to make up for the losses, but this is not sustainable in the long term. I believe the problem is caused, not only by climate change and habitat loss, but by the prophylactic use of chemicals and “health” products that are on the market, when the bees have managed for millions of years without the need for any of these “benefits”. Rant over!

Bees are an ideal society, that we, as humans, can learn something from. They work well together, are cooperative and care for one another. We are also more reliant on bees than we would like to think. Bees are guardians of biodiversity and ecosystems and are considered the invisible helpers of farmers across the globe. Of the 100 crop species that provide 90 per cent of the world’s food, over 70 are pollinated by bees. They also play a significant role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals of the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN). By acting as pollinators, bees promote biodiversity (Goal 15) and fight hunger (Goal 2). They provide decent jobs (Goal 8) in agriculture and other sectors, advancing Goal 1, no poverty.

Unfortunately, current human activities are detrimental to bees and other pollinators. Extinction rates of bees are 100 to 1,000 times higher than normal, this decline being mainly attributed to human activity. Across Europe, bee populations and honey stocks have been falling since 2015, in some places up to 30 per cent annually. The use of pesticides and loss of habitat due to farming and urbanisation are the most prominent causes, though bees’ survival and development are also threatened by climate change.

According to FAO, maintaining bee habitats and committing to more sustainable agricultural practices, including the use of indigenous and local knowledge and avoidance of pesticides, are key to safeguarding these species. Each of us can choose local organic produce when possible, and plant pollinator-friendly plants, such as shrubs and daisies, in our gardens. Even small, urban gardens can be instrumental in conserving bees.

What is interesting about bees is that the greatest diversity is in the temperate zones. Unlike almost every other creature, bees are more adapted to temperate climates, so the greatest diversity is in the belts across Europe and North America.

The Native Irish Honey Bee (Apis mellifera mellifera) is a strain of the Dark European Honey Bee which was once widespread across Northern Europe.

Tragically they are now scarce in most areas due to cross-breeding with other strains of the honey bee and diseases from imported bees. It is the only honey bee strain native to Ireland. Dark in colour and resilient to the unpredictable weather, this sturdy little native bee has many attributes that specifically aid it in prospering, including an ability to tolerate long periods of confinement to the hive in winter and an ability to fly at low temperatures and in drizzle or light rain! This is exactly what we see in our Cornish black bees which it is suspected are of similar strain. We are extremely fortunate that a strong and genetically diverse population of our native bee still exists, but it needs protection if it is to continue to survive and thrive.

So, hopefully, the wild swarms that I collect each year will help with the survival of our bees, at least locally. Interestingly, I haven’t had any more swarms this month, though I would have expected at least , if not two. I attribute it to the freaky weather we’re having, with the drought conditions this year not experienced since 1976. In fact, our well has run dry again this week, only the third time in 26 years. It makes us realise how much we take for granted in our daily lives. Let’s hope the bees can manage the situation better than we can – but then they’ve had more practice!

Colin Rees 01872 501313 07939 971104 colinbeeman@aol.com