How to create a garden

Our resident gardening expert gives us some advice on making a new garden.

I’ve been lucky enough to have been able to make a few gardens in my life. Only three for myself, but about twenty for friends and family, and even for some people who actually paid me! I am not a trained designer or gardener – but with that caveat I will dare to advise on how to make a garden.

Most people move into an existing property with an existing garden. Just as you decide on whether to reconfigure a house, make a new bathroom etc – you should look at a garden in the same way. Most people do not do this with their garden. There seems to be a strong impulse to conserve the existing structure and, particularly, the existing trees however boring or rubbishy they are. This is probably the major reason for what I call ‘restless garden syndrome’ – a dissatisfaction with compromise that results in constant rearranging and replanting.

Stage 1: Adapt or start again?

So the first decision to be made is whether the existing garden suits your practical and aesthetic needs. How will you use your garden? Is it for decorative purposes, is it for food production, or is it just a football pitch for the kids? Work out what you want from it and you can readily decide how radical you need to be.

Stage 2: Diagnosis

Make a list of questions and try to answer them – these will inform your design.

What are the physical constraints? Is the land flat, sloping, precipitous? How will you manage to work it? What is the access like? A terraced house may have no access except through the house itself or there may be only a small gate opening thus limiting the use of diggers or truck deliveries. Very steep or terraced gardens may also limit access.

What are the meteorological constraints? Is the garden exposed to strong winds, salt winds, full sun, part shade, full shade? How does the sun traverse the garden? Can you modify any of these – plant or build wind shelter, remove shading trees/fences etc?

What soil type/condition? Here on the Roseland the soil is largely derived from decayed slate so it is quite clayey and stoney if unimproved. If you are lucky, a previous occupier will have improved the soil with organic matter and it may be more or less deep before you hit the rock below. Dig a few test pits to see what it’s like – you may need to import soil and/or quantities of organic matter.

Where is water coming from and going to?

Is there too much or too little ground water in the garden? Does it flood in winter – dry out in summer? Does ground water come through your garden from land lying above yours?

Deer and rabbits? Do you need good fences? It is heartbreaking to lose your expensive and beloved plants and sometimes the little critters wait a few years before attacking just to make it hurt even more!

Stage 3: Design

How will you use your garden?

Make a list of needs and desires. What are your priorities? Can you have it all? How will different areas interconnect? In particular, remember to make a note of where the sun is when you take a coffee or tea break. Where would you want to be for outdoor dining? Is there wind shelter? A view?

Make a scale drawing of the entire garden and plot immovable objects and plants. Buy yourself some A1 graph paper for the plan of the plot and A1sheets of tracing paper for overlaying alternative designs. Get the land registry image of your property and use that to make an enlarged plan. An architect’s scale ruler is a useful tool.

Design the entire garden in general terms – do you want to subdivide it? What structures, seating, lawn, planting areas, ponds, terracing, paths, steps etc. do you want? Don’t frighten yourself – it doesn’t all have to happen at one time.

Stage 4: Developing the master plan

Work out the logistics of implementing your design

What can you afford?

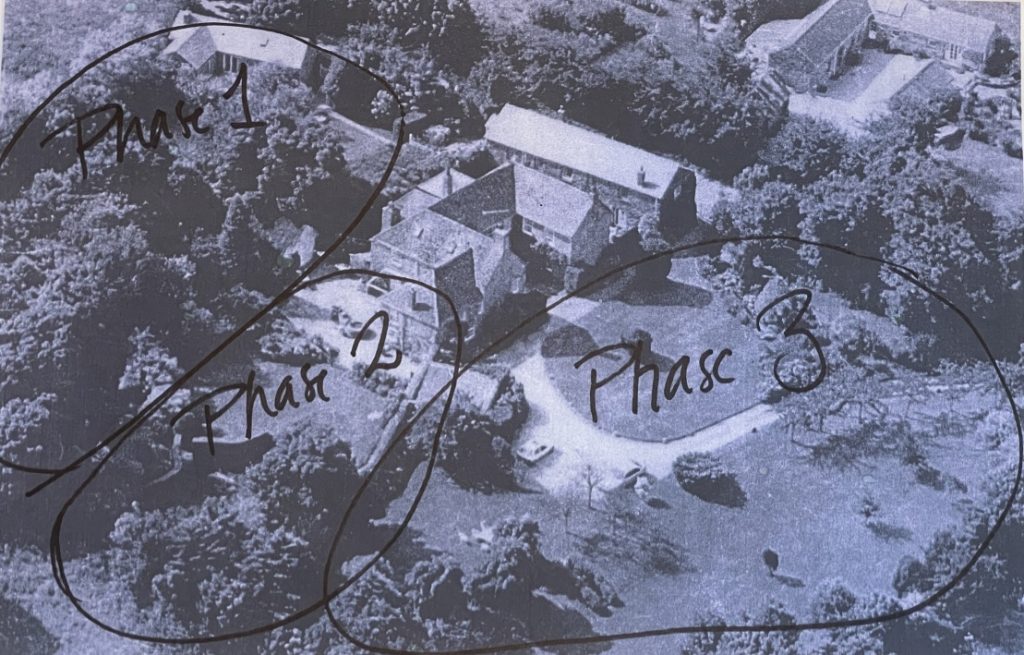

Phase the work: Even in a small garden it may be sensible to do the restructuring in stages. Structural work can be expensive – landscaping, paving, paths, walls, fences, gates, ponds, greenhouses, polytunnels, fruit cages, hen runs – whatever! The key here is to make sure that you don’t take on too much at once and that you don’t block access for later phases.

Cleaning up perennial weeds – don’t even think about planting until you have expelled ground elder, couch grass, horsetails and bindweed at the very least. And I mean really cleaned up – preferably before you put in any machinery that will spread the little bits of root. This means you may have to leave sections of your plot fallow for a full year to be sure – and dare I mention Round-up?

Soil preparation: The biggest mistake that I made in my current garden was a failure to improve the soil adequately before planting. The result is a constant struggle to establish plants on thin and rocky soils and constant remedial mulching and feeding. On a 2 acre plot, we did import over 400 tons of good field soil and many tons of well rotted manure and wood chip but it was not nearly enough. In a small garden, buying a truck load of good topsoil or spent mushroom compost at an early stage could save you a lot of grief in future.

Soil compaction after landscaping with machinery must be remedied. Compaction is the greatest enemy of lawns and plants sensitive to water logging. Hiring a rotavator will save you time as well as your back. If compaction is really bad – perhaps close to building work – you can even hire in a machine that pumps air into the ground at depth. Sounds like fun!

Water: We have always had a problem with too much water in Cornwall – particularly in winter – which can do a lot of damage to roots. In recent years we have also had some prolonged droughts. So you should consider both supply and drainage. Now is the time to put in water pipes and taps in different parts of the garden. Now is the time to lay land drains if needed -particularly under lawns and permanent plantings. What happens to your roof water? Could you conserve any of it – and I don’t mean a barrel for filling up a watering can – I mean a substantial underground tank. Consider whether your water management can be used to create a wet area of the garden, bog or pond rather than draining into already overloaded mains drains.

How much labour can you buy in? Buying in mechanised labour is really cost- and time-efficient in a new garden, both for removing unwanted plants and structures, and for re-landscaping. I love a JCB – if I had another life I’d be a digger driver! A mini-digger is a wondrous beast as well.

Will you have gardening help once established? If so, what level of skill will you need ? Someone to mow and cut hedges or someone with real plant knowledge who won’t prune at the wrong time or weed out your precious darlings?

Stage 5: Lay out the garden

Use your scale drawings to lay out the structures- lawns, borders etc. Depending on how accurate you need to be – it pays to invest in or borrow a few bits of kit:

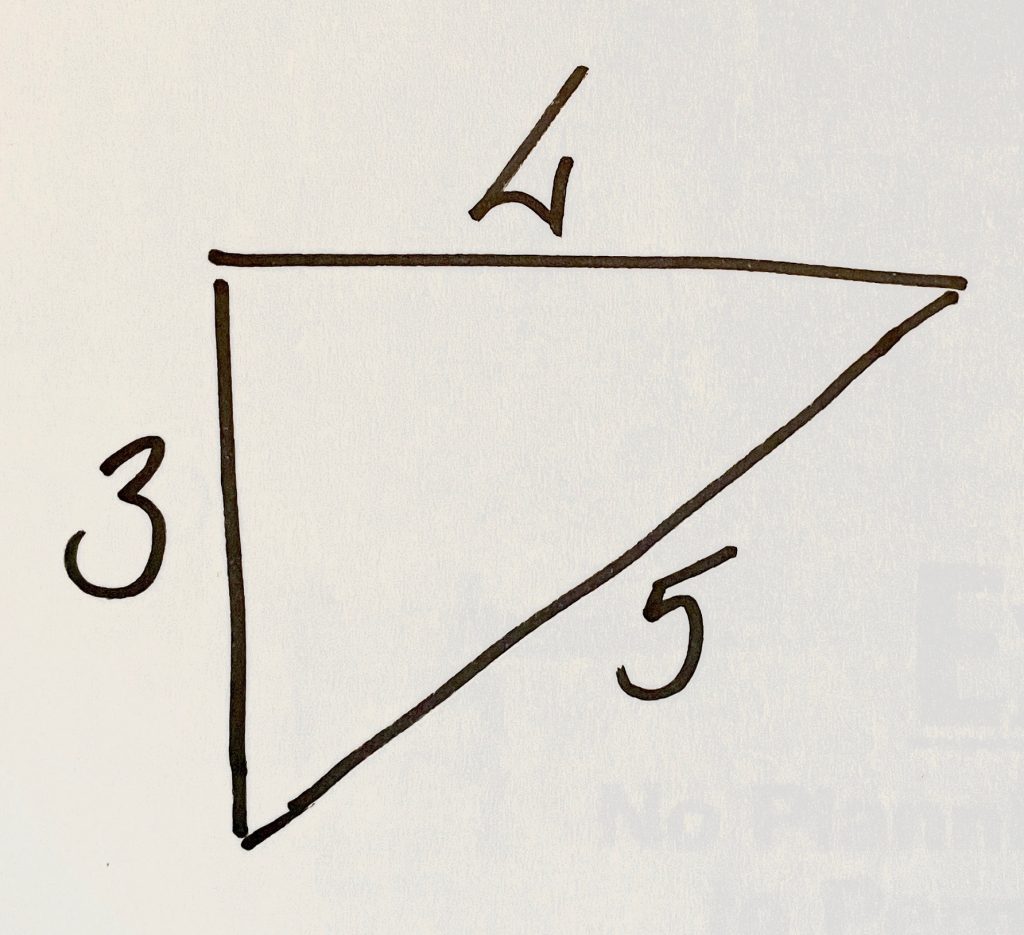

1. Three decent measuring tapes and some pegs : two tapes of 50m and one 10-20m. Three tapes allows you to make a right angle on the ground using the 3/4/5 formula.

How to make a right angle: Use the 3:4:5 ratio to get a right angle.

2. A long hose or rope – for laying out circles or irregular forms.

3. Spray cans of ground paint – for marking out your masterpiece on the ground.

4. If you are employing digger drivers to alter levels then they will have laser levels etc.

Planting:

How much to plan?

A garden designer will plan every last daisy and fully plant the whole plot in one go. But, if you are doing your own planning, it is probably less mind-boggling and more fun to be a bit more impulsive. Having said that I am certain that planning the woody plants – the bones of the garden – is really essential. Trees and shrubs do not like being moved about so getting the right ones in the right place from the get-go is vital. Non-woody plants are less damaged by being moved so if you get these wrong it’s less impactful.

Plants are expensive nowadays – perennials in particular – so planning the major components will save you money as well as time. You may need to buy just a couple of each plant and start propagating from them to make larger plantings. If you plan out your permanent planting, you can fill in the early gaps with cheap annuals grown from seed while you build up your perennials and bulbs etc.

Take your time over deciding what plants to use. Take note of what is growing well in neighbouring gardens but don’t be ruled by them. In Cornwall, the dominance of Victorian ‘plant hunter’ gardens and their wonderful magnolias, rhododendrons etc have given rise to the idea that that is what you have to plant here. It isn’t true – we have a wonderfully long growing season and a mild climate that allows us to grow a fantastic range of plants.

Equally don’t get too embroiled in the current fashions – notably rewilded gardens and prairie gardens. Gardens are gardens, intrinsically man-made and a wider range of plants than our native palette alone can bring both aesthetic and ecological benefits. Prairie gardens are not well suited to our damp warm winters – I cannot get that Piet Oudolf favourite, Echinacea, througha Cornish winter!

The internet has made reference books largely redundant but there are some that I could not be without. Hilliers Trees and Shrubs is a bible – a great birthday present or worth borrowing from a library. It is pretty comprehensive and gives details of ideal growing conditions, form, and size at maturity. Specialist nursery catalogues are also useful – on or offline.

Stage 6: Sourcing your plants

Having decided on your plant portfolio – where do you get them from? I try to source locally but also buy from far-flung nurseries – sometimes on plant hunting expeditions but quite a lot online.

Locally, there are several nurseries that mostly grow their own plants:

Burncoose is the best for trees and shrubs but can miss the good ordinary garden plant.

Lower Kennegy Nursery specialises in coastal plants.

Trevenna Cross has a wide range suitable for the Cornish climate.

Treseders has a nice selection of good value trees and lots of yummy specialist plants like the Australian mint bushes (Prostanthera sp) and ginger lilies (Hedychium sp) that do so well here.

Bodmin Nursery – used to be Bodmin Herb Nursery -they do grow herbs but a fantastic range of other plants as well including fruit trees and soft fruit.

Other local nurseries that mostly buy in and grow on are:

Pengelly – they have a good eye for new cultivars as well as old reliables. Their presentation is so good that its hard not to leave with at least one new jewel.

Hayle Plants – a great range of plants including a lot of succulents.

Duchy – sadly a once great growing nursery – now more of a garden centre and lunch destination. Nevertheless it still has a good range of quality plants – particularly trees and shrubs.

I access specialist nurseries online – hedges, roses, bulbs, fruit trees and alpines. They usually have a greater range than generalist nurseries and offer excellent advice as well.

Common mistakes:

Over-planting of trees and shrubs. Its important to work out how much space they will take up in 5/10/15 years. You can plant ‘sacrificial’ shrubs that you plan to remove as others enlarge – but there is a risk that you won’t do it until it’s too late and you’ve destroyed the natural form of the ‘chosen ones’. It may be better to inter-plant ground-cover plants that will just get swallowed up over time.

Using plants that don’t work together in terms of colour. Some gardeners get away with putting clashing colours together – famously Christopher Lloyd pioneered some brilliantly loud flower borders at Great Dixter but in other hands it can just look brash.

Bad planting

I, personally, don’t like very clashy foliage colours together either – remember those conifer and heather gardens of the 1960’s with blue and lime and purple leaved species in island beds? But…. each to his own.

Using plants that don’t work together in terms of form – we inherited bananas planted next to Cupressus leylandii, next to a Dracaena palm for example!

Using plants that don’t suit their location, shade, sun, dry, damp, poor soil, good soil etc. Understanding where a garden plant comes from in its native form will help you give a plant its best life – and, in general, plants from the same type of environment also look well together. For example, grey-leaved and spiky plants, both adapted to dry conditions look like they belong together too.

Beth Chatto was a gardener who promoted the design of gardens that grouped plants according to their natural habitat. Her 7.5 acre garden in Essex has a gravel garden for dry plants, a scree garden for alpines, a water garden for pond and marginals and a woodland garden. Well before ‘rewilding’ was a thing, she wrote several books on ecological and sustainable planting – her mantra was- right plant, right place. It’s a good one.

And finally – remember to have fun – its your party….