Ugh… That Mud Tastes Horrible!

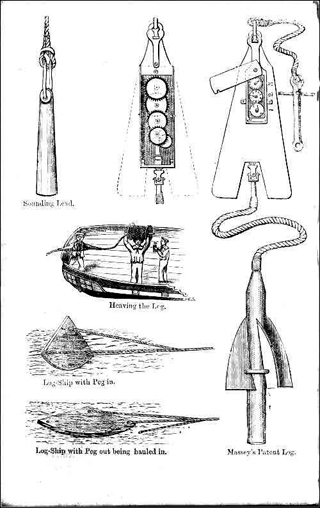

I have written before about the difference between then and now and the skills used by the ‘old timers’ which have long since disappeared. Who now, for instance, uses a lead line? This was a chunk of lead weighing about nine pounds attached to a long length of line. The line was marked with a series of ‘symbols’ such as a number of knots, pieces of leather, calico or linen. The theory is that, when dropped into the water the depth will be measured by where the water comes to on the line. The purpose of the ‘symbols’ was to identify the depth and to enable the leadsman to read, by feel in the dark, what the depth of the water was.

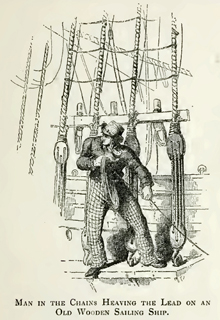

Dropping it over the side of a stationary vessel was fine but seldom needed. What was wanted was to know the depth of water as one approached the shore or a sandbank, feeling your way into a narrow passage in a moving ship. The leadsman would stand up in the bows, sometimes on a specially designed platform, known as ‘chains’ swing the lead in a vertical half circle and throw it so that it hit the water ahead of the ship. By the time the lead hit the bottom the line would be straight up and down and he would be able to shout to the men on the bridge or poop what the depth was.

Traditionally there were ten marks signifying various depths, uniform in the sailor’s world, so that a leadsman could move from ship to ship and they would all be the same. If the water came close to the mark he would cry out “By the mark seven (fathoms)”, for example, and if it was between marks he would call out “By the deep six”, being the mark which had been submerged. It was a skilled and energetic task, the line was seventy feet long– you try whirling a nine pound weight, throwing to forward, then frantically haul it in again, coiling it as you go – not once but many times!

It didn’t stop there. The base of the lead was hollowed out and this was filled with tallow. When the weight hit the bottom a certain amount of material from the bottom would come back up with the lead so, by looking at it, you could tell if you were on sand, shingle, stones or rock. It is said that the East Coast fishermen were so skilled in their own backyard that even in fog they could say exactly where they were by looking at the sample and even tasting it!.

Ironically the lead survives to this day, in use by modern survey vessels, not to measure depth but to bring up samples from the sea bed. I am not sure that they use tallow in the bottom of it now though – probably a modern synthetic.

Of course it gave a phrase into our language today. ‘Swinging the lead’ means a shirker and probably came from the man in the chains just whirling the weight without throwing it and shouting out a fictitious depth thus saving himself work On a large ship, or in the dark, he could probably get away with this as he could not be seen fully from the poop. Possibly it also gives us the expression ‘fathoming’ something – whether you can understand something.

Of course it gave a phrase into our language today. ‘Swinging the lead’ means a shirker and probably came from the man in the chains just whirling the weight without throwing it and shouting out a fictitious depth thus saving himself work On a large ship, or in the dark, he could probably get away with this as he could not be seen fully from the poop. Possibly it also gives us the expression ‘fathoming’ something – whether you can understand something.

A ship’s speed is measured in knots, a knot being 1 nautical mile or 2000 yards – to be very precise it is 2025 yds. This is measured by a log, not the wooden sort you burn, but originally something you towed behind. In the last two centuries this was a spinner, just like a large fishing lure, which rotated. It was attached by means of a special line to an instrument on the ship, just like a car odometer, and the spinning line turned the spindle in the instrument which recorded how far the ship had travelled. Simple timing gave the speed per hour.

Before this device was invented they used a triangle of wood on a very long line, the wood being weighted along one side so it stayed upright in the water. Dropped over the side its flat surface gave enough resistance to pull the line through the operators hand. The line had knots in it at set distances so the operator simply counted the knots as they went through while an assistant checked time with an hour glass. A simple calculation would give the ship’s speed – hence the speed was quoted in knots. This was supposedly invented by the Portuguese sailors but an even more primitive method was known as a ‘Dutchman’s Log’. A lump of wood was dropped over from the front of the boat and its passage to the stern was timed. They knew the distance from bow to stern so they could gauge, roughly, how fast the boat was travelling.

Much of the ancient craft of seafaring has now been lost in the advent of the electronic age. Ships know exactly where they are, down to a few metres, by use of satellite communications or G.P.S. (Global Positioning System). Coal fired steam has given way to diesel electric engines. No need now for a team of men whose sole job was to feed a boiler fire. One man can do the job, sitting at a control console in a smart suit.

The shipping container has largely taken over the transit of goods by sea – loading and discharging is a couple of men on the ship and one man on a crane. Gone are the crews of dock workers and a large deck crew to handle the ship end of things. Even steering wheels are disappearing – the latest ships use a joystick arrangement where a helmsman controls the rudder with one hand and there will be only him and one officer of the watch on the bridge.

But the Gremlins are alive and well. The big failing with electronics is that occasionally they go wrong. The failure can be more serious because no one is expecting it. There may be no ‘fall back’ equipment aboard or, if there is, lack of use means no one is practised in how to do it. The problem may be deeply electronic and no one on board has the skill to fix it. So even big ships get into difficulties, as witness the fairly frequent of arrival of ‘breakdowns for repair’ at Falmouth.

N.C.I. have little to do with these – but failure of sophisticated parts is not confined to large vessels. These days virtually every yacht and motor cruiser carries electronics in engines, navigation and safety equipment. The average amateur sailor is well versed in operating his gizmos but when they go wrong can only cry ‘Help’. Think of your car.

These days how many of you can lift the bonnet and mend it. When it doesn’t work you can always get out and walk – not so if you are a mile off Nare Head and the wind is blowing you towards the Whelps. Then you don’t need to ring the A.A. You need to shout ‘Mayday, Mayday’ – and quickly. The calm voice of the Coastguard at Falmouth will come up asking your problem, assessing your difficulties and needs. In a few minutes a Lifeboat is on its way. Your call has also been heard by the N.C.I. volunteer at our Lookout.

The Coastguard will next call us to ask if we can see the casualty. Assuming we can we will be asked to keep an eye on you and help guide the Lifeboat to your aid. Sometimes the Coastguard only gets a bit of the message, or you are not sure of exactly where you are. Again MRCC will ring us to see if we can see the casualty and tell them where the Lifeboat should go. We are, indeed, their ‘Eyes along this bit of Coast’.

Pictures by courtesy Wikipedia