Say It With Flags

My son-in-law has just given me an old mobile phone – at least it is an old one to him but a mysterious piece of wizardry to me. Like many of my generation I belong to the press buttons and see what happens brigade – with no clear idea of what does what. I manage the basics but that is it, and I marvel to see my grand children dextrously dealing with this fiendish gadget in one hand, their fingers moving at speed, composing a message. What a far cry from some twenty years ago when we took them to the exhibition at Goonhilly and they played with the old fashioned experiment – two tins with a bit of string between which they could use as a telephone!

My son-in-law has just given me an old mobile phone – at least it is an old one to him but a mysterious piece of wizardry to me. Like many of my generation I belong to the press buttons and see what happens brigade – with no clear idea of what does what. I manage the basics but that is it, and I marvel to see my grand children dextrously dealing with this fiendish gadget in one hand, their fingers moving at speed, composing a message. What a far cry from some twenty years ago when we took them to the exhibition at Goonhilly and they played with the old fashioned experiment – two tins with a bit of string between which they could use as a telephone!

Communication is the oil that lubricates civilisation. If you cannot communicate you cannot understand. In its earliest forms it was simply signs but they have limited range. There was a need to communicate over long distances so signalling methods were devised. The American Indian used smoke signals, no good in the dark or in a high wind. Some people have used drums but, unless you can use them in some form of code, of only limited use.

Before the electric telegraph by far the two most effective methods were light and flags. If you go back before the invention of the light bulb it had to be flags – even if these were in the form of solid plates like the arms of a semaphore, or a design carried on a pole, like the Roman legions. So we see that there were two reasons for flags, to pass a message or to give designation to an object or person. In the latter case they would be a rallying point, somewhere to gather round your leader or company of men.

Before the electric telegraph by far the two most effective methods were light and flags. If you go back before the invention of the light bulb it had to be flags – even if these were in the form of solid plates like the arms of a semaphore, or a design carried on a pole, like the Roman legions. So we see that there were two reasons for flags, to pass a message or to give designation to an object or person. In the latter case they would be a rallying point, somewhere to gather round your leader or company of men.

Knights in armour carried them so they could be identified – there was no other way in which you could see what was in the tin. They became symbols of honour, flying over castles showing how important the lord was and if he was in residence. They were carried at the heads of armies and regiments. The colour sergeant, the man who carried the colour, held a prestigious position, so much so that he was given an escort of two junior officers to protect the colour and him – in that order.

From the Napoleonic wars onwards there would be two colours, the national flag and the regimental colour, many of which can now be seen hanging in churches around the country, the regiments themselves long disbanded and forgotten. The disgrace of losing a colour was such that many men died simply to protect this piece of cloth, to stop it falling into the hands of the enemy. After the defeat of the British Army at Isandlwana two young lieutenants, Melvill and Coghill, gave their lives in trying to save the colours from the Zulu army, the place where they died known today as Fugitive’s Drift.

Ships also carried ensigns for recognition purposes, principally national flags, but in navies ships carried flags to identify the squadron to which they belonged or the Admiral. National ensigns would be dipped as a sign of respect or lowered to indicate surrender. A whole, complicated etiquette has arisen around the use of flags and ensigns on ships but sufficient here to say that, so far as we are concerned, there are three – red, white and blue.

Ships also carried ensigns for recognition purposes, principally national flags, but in navies ships carried flags to identify the squadron to which they belonged or the Admiral. National ensigns would be dipped as a sign of respect or lowered to indicate surrender. A whole, complicated etiquette has arisen around the use of flags and ensigns on ships but sufficient here to say that, so far as we are concerned, there are three – red, white and blue.

The red ensign is worn by any vessel registered or owned in the United Kingdom, with exceptions. The white ensign, a St George’s Cross on a white background, defaced with a Union Flag in the first quarter, is the prerogative of the Royal Navy, the Royal Yacht Squadron and, in some circumstances, ships of Trinity House.

It gets more complicated as the Navy owns a few sailing yachts which can fly the ensign because of ownership, and a Naval Officer with his own yacht can apply to fly an un-defaced white ensign. This is why we occasionally see what is apparently a leisure yacht in our waters displaying this flag. There are a few other odd ones, e.g. navies of Commonwealth Nations can wear the ensign defaced with their own national flag and yachts of the Royal Irish Yacht Club may also fly it defaced with an Irish national flag. I said it was complicated.

It is much more common to see a blue ensign, plain blue, defaced with a Union Jack in top left corner. This can be worn on a vessel owned by an RNR Officer who is on board at the time. It is also awarded by Royal Warrant to certain yacht clubs whose members are entitled to fly it as an ensign. These are fairly frequent visitors to our waters.

It is much more common to see a blue ensign, plain blue, defaced with a Union Jack in top left corner. This can be worn on a vessel owned by an RNR Officer who is on board at the time. It is also awarded by Royal Warrant to certain yacht clubs whose members are entitled to fly it as an ensign. These are fairly frequent visitors to our waters.

But in days gone by the principal use of flags was signalling. There are 26 letter flags, nine number flags and four substitute pennants. Just to confuse the issue there are nine number pennants which can substitute for number flags. In case you are getting bored, letter flags flown singly or in combinations which do not make up a word have their own meanings, a sentence in itself, such as, ‘I am leaking a dangerous cargo – keep clear.’ Or ‘I require medical assistance.’

There may even be one which means, ’The cook has just put the kettle on’. There is certainly an ‘unofficial’ hoist of the letters R.P.C. which mean’ Request the Pleasure of your Company’, otherwise known as the Gin Flags. When flags were important in signalling every vessel of any size carried a comprehensive flag locker and at least one person who had the specific duty of dealing with them. Even today ships must carry them as the hoists of several flags at a time are still mandatory to indicate what a ship is doing – such as those above and ‘Keep Clear of Me’ , or ‘I Require Assistance’ etc.

Fortunately, though we learn a bit about flags, our syllabus is confined to 10 and, at risk of being hit over the head by my Station Commander, I will say that, so far as we are concerned at Pednavaden, we only need to know two. These are flag ‘A’ which means, ‘I have a diver down’, common in our local waters, and the combination ‘N’ and ‘C’, which, flown together, is a distress signal. I am sticking my neck out because yachts under 40 feet find it difficult to carry a set of signal flags and, I suspect. Few under 50ft do so either.

Fortunately, though we learn a bit about flags, our syllabus is confined to 10 and, at risk of being hit over the head by my Station Commander, I will say that, so far as we are concerned at Pednavaden, we only need to know two. These are flag ‘A’ which means, ‘I have a diver down’, common in our local waters, and the combination ‘N’ and ‘C’, which, flown together, is a distress signal. I am sticking my neck out because yachts under 40 feet find it difficult to carry a set of signal flags and, I suspect. Few under 50ft do so either.

Once you get over that size you move into a different area of maritime regulations. I always carried a Red Ensign, Irish and French flags and some people will carry bunting to ‘dress overall’ and look pretty on occasions, but, if we are honest, that is it.  Even the hoisting of anchor balls to say you are at anchor or cones to say you are motor sailing are not common. Large shipping is too far out for flags to be seen unless they come close to anchor and, even then, the most you are likely to see is an anchor ball. If they get into difficulties they have large and sophisticated radios and talk direct to Falmouth Coastguard.

Even the hoisting of anchor balls to say you are at anchor or cones to say you are motor sailing are not common. Large shipping is too far out for flags to be seen unless they come close to anchor and, even then, the most you are likely to see is an anchor ball. If they get into difficulties they have large and sophisticated radios and talk direct to Falmouth Coastguard.

So, while as part of your training you will be told about flags, it is nothing to get worried about. A crib sheet is always available in the Lookout should you need to look one up, but usually flag knowledge forms part of the lighter side of training – something the Training Staff sneakily put in to one of our light hearted training quizzes which we have from time to time at our evening meetings. As for the ‘A’ flag – well, you will see it so often that it will give you no difficulty.

At this point I will sign off with the Flag ‘V’ – What does that mean? ‘I am not in distress but I require assistance’ – and so do we. Still not enough people to cover every day of the week

At this point I will sign off with the Flag ‘V’ – What does that mean? ‘I am not in distress but I require assistance’ – and so do we. Still not enough people to cover every day of the week

Perhaps could you hoist to say ‘Yes’ you will help.

Perhaps could you hoist to say ‘Yes’ you will help.

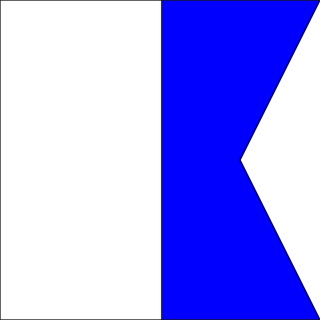

Or perhaps ‘K’ – ‘you want to communicate’.

Or perhaps ‘K’ – ‘you want to communicate’.

I could do these telephone numbers in flags but it would take too much space – so try 01872 580720 and speak to Bob or 501670 and speak to Robert.