I Don’t Trust This New Fangled Machinery

Watching from the Lookout the other day I saw the Richard Cox Scott, our local lifeboat on her way back to Falmouth. A magnificent, powerful, vessel capable of keeping at sea in all weathers, she was a fine sight. So manoeuvrable, so powerful, so ‘crew friendly’ in the shape of giving them shelter, I could not but wonder what it must have been like at the turn of the 19th/20th century when the volunteers rowed open boats, many miles to a stricken ship. It was about this time that the first experiments were being undertaken by R.N.L.I. in fitting engines to their boats. The old timers regarded these with deep suspicion, new fangled machinery in which they had little faith.

Watching from the Lookout the other day I saw the Richard Cox Scott, our local lifeboat on her way back to Falmouth. A magnificent, powerful, vessel capable of keeping at sea in all weathers, she was a fine sight. So manoeuvrable, so powerful, so ‘crew friendly’ in the shape of giving them shelter, I could not but wonder what it must have been like at the turn of the 19th/20th century when the volunteers rowed open boats, many miles to a stricken ship. It was about this time that the first experiments were being undertaken by R.N.L.I. in fitting engines to their boats. The old timers regarded these with deep suspicion, new fangled machinery in which they had little faith.

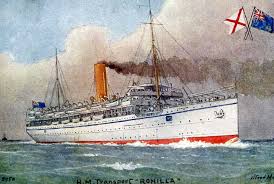

But an incident occurred on 30th October 1914, the centenary anniversary just past, which was to change a lot of thinking. It was the time of the First World War and a hospital ship, the Rohilla, was setting out from Queensferry on the east coast of Scotland, heading for Dunkirk, to collect wounded soldiers. There were 229 crew and medical staff aboard. She sailed south along the English Coast, a dark night, with an easterly gale blowing her toward the hidden shore under her lee.

As it was wartime all navigational lights had been extinguished lest they help the enemy so the Captain had little to guide him and he did not realise that he was being pushed closer and closer to the rocks. She eventually struck, not far from Whitby, and was driven up onto a reef. The fierce sea immediately broke the ship in two, the stern half being swept out into deep water where it sank with all who were aboard. The front section, on the rocks, battered by the waves, with about 150 people still aboard.

A Whitby Coastguard had seen her run aground and started the alarm that went up and down the coast. There were lifeboats at Whitby, Scarborough, Tees mouth, Up gang and Tynemouth. All, save the last, were rowing boats and their crews set out to fight their way to the wreck. The Whitby boat got there and, in two runs, rescued 35 people but was then so badly damaged that she was unable to put to sea again.

The second Whitby boat, Tees mouth and Scarborough were beaten back by the weather and unable to get to the wreck. The Up gang boat was dragged by horses two miles across country to the cliff top at Whitby with the intention of lowering with ropes – but that idea was abandoned. All seemed lost – it looked as if another 50 odd people still clinging to the wreck would be drowned. But the boat from furthest afield, the Tynemouth boat, the only one fitted with an engine, was battling its way on a 44 mile journey through the night.

The second Whitby boat, Tees mouth and Scarborough were beaten back by the weather and unable to get to the wreck. The Up gang boat was dragged by horses two miles across country to the cliff top at Whitby with the intention of lowering with ropes – but that idea was abandoned. All seemed lost – it looked as if another 50 odd people still clinging to the wreck would be drowned. But the boat from furthest afield, the Tynemouth boat, the only one fitted with an engine, was battling its way on a 44 mile journey through the night.

They stopped at Whitby and collected some barrels of oil, then went on. The Rohilla had now been on the rocks for two and a half days, the remaining survivors near the end of their tether. When the Henry Vernon reached the wreck they poured gallons of oil into the sea and the waves appeared to suddenly flatten. Her coxswain laid her alongside, holding her there with the engine, while the remaining survivors climbed down to safety.

This rescue showed without any doubt the advantages of an engine over oars. One man on the controls could keep the boat in position while his crew could assist the survivors to get on board. They had the power to make a long journey to the wreck whereas rowers over such a distance would be exhausted long before arrival. With an oared boat it was nearly impossible to lie alongside a wreck. That meant bringing in one bank of oars, losing half the power and what was left went all to one side making manoeuvring very difficult.

The boated oars obstructed the inside of the boat when room to jump and move about was most needed. They had valiantly served their time but it was demonstrated that the oared boat was now obsolete. Even so, it would be several years before engines became universal, simply because of the time and money needed to design and build replacements. So there was I thinking of the fast, efficient Richard Cox Scott which could have reached the Gull Rock in half an hour, the crew tucked up safely inside, and comparing the case of the Falmouth pulling boat of 1914, the Bob Newbon, which struggled for several hours, fighting a winter’s gale, the crew exposed to the cold and snow as they rowed to the Hera, and, when they finally got there, had to use oars to manoeuvre the boat into position to get the survivors out of the rigging. Verily, they were men in those days!

The boated oars obstructed the inside of the boat when room to jump and move about was most needed. They had valiantly served their time but it was demonstrated that the oared boat was now obsolete. Even so, it would be several years before engines became universal, simply because of the time and money needed to design and build replacements. So there was I thinking of the fast, efficient Richard Cox Scott which could have reached the Gull Rock in half an hour, the crew tucked up safely inside, and comparing the case of the Falmouth pulling boat of 1914, the Bob Newbon, which struggled for several hours, fighting a winter’s gale, the crew exposed to the cold and snow as they rowed to the Hera, and, when they finally got there, had to use oars to manoeuvre the boat into position to get the survivors out of the rigging. Verily, they were men in those days!

As I write this we are thinking about the tragedy in Mawgan Porth where three people lost their lives, apparently trying to rescue several teenagers in difficulty in a rip current. The inevitable questions are being asked as to whether there should have been R.N.L.I. lifeguards on the beach. Cover had been suspended a week or so before as it was considered that the ‘season’ had come to an end and it was normal practice to withdraw cover from many beaches at this time of the year.

The situation is complex and I do not intend to enter into the possible rights and wrongs as I always feel that in instances like this hindsight is a wonderful thing. But it has raised the question in my mind. As things stand at the moment at our Portscatho Station we do not have enough volunteers to cover every day of the week. Decisions had to be made and, while weekends and Bank Holidays are obvious, I suspect that it was almost a toss of the coin as to which weekdays we should cover. One day had to be left out and that is Tuesday. But Tuesdays can also be blazing hot and sunny with people flocking to our beach.

Yachts still sail by on Tuesdays. So what happens if someone gets in trouble that day, in the worst instance a fatality, and we have no one in the Lookout who might, possibly, have raised the alarm? You can be sure of one thing – QUESTIONS WILL BE ASKED! We also have to finish our normal daily cover in the school holiday period at 6.30pm. Yet on a good day it can be fine and sunny with people still in the water. I know our Management Committee are asking themselves questions about how long and when we should cover, but their hands are tied by shortage of volunteers.

We really do need more It is not difficult, you don’t need any previous experience, age may not matter, you just need to be fit enough to walk out along the cliff path, and it is a worthwhile job. We now have increasing numbers of ladies. We would dearly like to have some young people who would be prepared to give up some time at the weekend. We have some volunteers who have full time jobs and manage to fit us in around their work hours. So please give it a thought. We are a congenial group and duties are arranged to suit you. You do not commit yourself to any set regular hours – you chose your own. So give Robert a ring on 01872 501670 or Bob on 580720. They will tell you more and, if you are still interested, arrange for you to come and meet some of us so you can dig deeper.

Pictures by courtesy of R.N.L.I.