Why Don’t Ships Blow Sideways?

I wrote last month about a motor cruiser in the bay being blown seawards because of a dragging anchor and that set my mind thinking. Wind is the sailors greatest friend and his worst enemy. It drives his vessel through the water and also on to the nearest rocks. It will waft him gently along under a clear blue sky then raise great waves which threaten to overcome him. It is a power to be reckoned with.

I wrote last month about a motor cruiser in the bay being blown seawards because of a dragging anchor and that set my mind thinking. Wind is the sailors greatest friend and his worst enemy. It drives his vessel through the water and also on to the nearest rocks. It will waft him gently along under a clear blue sky then raise great waves which threaten to overcome him. It is a power to be reckoned with.

The view from out NCI Lookout encompasses the area from Greeb Point to Nare Head, though in good conditions it is possible to see a bit further in each direction, depending on the angle of the object from the Lookout. Straight out to sea on a clear day the horizon is about ten miles, the tidal path running from Zone Point, just this side of Falmouth, to Nare Head. The Bizzies are an underwater reef lying about a mile off Greeb, deep enough to be no danger to small boats, but used by fishermen with lobster pots.

Here the tide is strong enough to make the pot flags lean over and create a small race but move inside the line from Greeb to Nare Head and you lose the tide. Within the Bay in front of us it is not the tide that is the governing factor but the wind. Our Watchkeepers know that a westerly wind of about Force Three and above makes it very easy to paddle from Porthcurnick around Pednvaden towards Nare – but hard going coming back. We record wind direction and force in our log book from frequent readings of our weather station so we know the effect the wind will have on a swimmer or boat in difficulties up to a mile offshore.

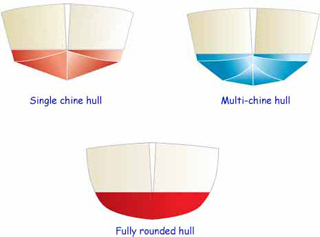

If the wind produces so much force against a kayak why does it not have the same effect on a sailing vessel? If it will blow a kayak backwards or sideways why not a vessel with sails up? There is a much greater ‘blowing surface’ on a set of sails than on a kayak. The reason is grip on the water – the amount of the sailing boat which is below the water and offers resistance to the pressure of the wind.

If the wind produces so much force against a kayak why does it not have the same effect on a sailing vessel? If it will blow a kayak backwards or sideways why not a vessel with sails up? There is a much greater ‘blowing surface’ on a set of sails than on a kayak. The reason is grip on the water – the amount of the sailing boat which is below the water and offers resistance to the pressure of the wind.

The same affect can be seen with a swimmer in the water. Even if exhausted and just treading water his lower body will prevent him from being pushed sideways at the same speed as a kayak which is not being paddled as the kayak has very little of its hull below the surface. So, as we teach our trainees, when assessing drift of a casualty, you must think about what it is and expect something like a kayak to be blown to windward faster than an exhausted swimmer.

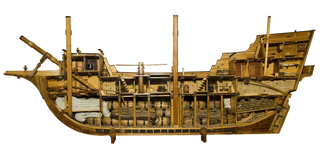

Boats with sails have developed over the centuries and, like every other tool that man uses, their design is influenced by the purpose of the vessel. Early cargo vessels were tubby so as to accommodate as much cargo as possible. The cargo would be put low down, obviously the heavy objects at the bottom. This pushed the ship lower in the water therefore giving it ‘grip’ in the same way as our swimmer’s body.

To start with they were very cumbersome, almost bulbous inshape, but man realised that if they could be made slimmer they would move faster. The only way to do this and carry the same amount was to make them deeper, and so evolved the brigs and barques of the deep water trade in the 18th and 19th centuries. Then came the trade with China and the tea crop. Harvested at a certain time of the year tea was a very valuable commodity and was sold on big commercial markets in London and Europe.

To start with they were very cumbersome, almost bulbous inshape, but man realised that if they could be made slimmer they would move faster. The only way to do this and carry the same amount was to make them deeper, and so evolved the brigs and barques of the deep water trade in the 18th and 19th centuries. Then came the trade with China and the tea crop. Harvested at a certain time of the year tea was a very valuable commodity and was sold on big commercial markets in London and Europe.

The first ship to get to market got the best price. So the search was now on for faster sailing ships and we got the clipper. Square rigged, long and slim, very lightly built to keep the weight down they were the fastest things afloat and had a long, deep keel to give maximum grip and directional stability. The penalty was that, as they were built of softwoods for lightness, they did not last and rotted out after about twenty years. Cutty Sark can be seen at Greenwich in London, the last remaining one preserved in dry dock.

Earlier in development still was the Thames barge. This needed to go a long way up shallow rivers which were tidal. When the tide went out there was an expanse of mud. If they wanted to unload a barge against a quay some twenty miles inland it could not be done in one tide so the vessel must be capable of sitting on the bottom and staying flat so men could work – so they made the barges flat bottomed but they had to be of shallow draft to get up the river.

Earlier in development still was the Thames barge. This needed to go a long way up shallow rivers which were tidal. When the tide went out there was an expanse of mud. If they wanted to unload a barge against a quay some twenty miles inland it could not be done in one tide so the vessel must be capable of sitting on the bottom and staying flat so men could work – so they made the barges flat bottomed but they had to be of shallow draft to get up the river.

These vessels would trade back and forth across the North Sea and were prime candidates for being blown sideways rather than going ahead once away from the sheltered rivers. They got round this by fitting lee-boards, things like massive doors which were bolted with a single bolt on each side of the vessel. As they pivoted on the bolt they could move up and down with the aid of a rope on a winch.

One on each side they would lower the board on the side away from the wind, or the lee side, and as the wind tried to push the vessel sideways the boards was forced against the ships side and could not move. It hung down below the bottom of the barge and gave it a grip on the water, translating the winds power to force it sideways into to a pushing action, the orange pip effect. You know what happens if you squeeze a pip between finger and thumb, you spent hours doing it as a child to the annoyance of your mother. The pip is forced to fly out forwards, converting the sideways pressure of your fingers into trajectory.

All modern single hulled yachts have a deep keel. There are many designs and variations but the principle is the same. Grip on the water prevents the vessel from going sideways and translates that into forward motion. The Victorian fishermen had this down to a fine art. They were not interested in going round the world fast. Their calling was to go out into the coastal waters and fish. This called for a steady platform as the steadier it was the easier it was to work.

All modern single hulled yachts have a deep keel. There are many designs and variations but the principle is the same. Grip on the water prevents the vessel from going sideways and translates that into forward motion. The Victorian fishermen had this down to a fine art. They were not interested in going round the world fast. Their calling was to go out into the coastal waters and fish. This called for a steady platform as the steadier it was the easier it was to work.

The easier to work the fewer men needed to do the job. Few coastal fishing boats, out for no longer than a couple of days, carried more than three men, but hauling a long net called for a winch. You needed one man to work the winch and two to gather the huge net in as it came over the stern. That left no one to steer the boat. So they devised a different type of keel, very deep in proportion to the boat and much deeper at the stern that at the bow. A boat 45ft long would have a keel that was 10ft deep at the stern. They did not need to worry about drying out to unload as they worked out of deep water ports like Lowestoft and Grimsby.

A long, deep keel of that shape meant that with just enough sail set to give her headway they could leave her to her own devices while the full crew worked the net. She would just gently make her way to windward, a steady platform on which to work. Then, once the fish hold was full, they set sail for home. The large keel meant they could carry a huge amount of sail so they were fast. Fish goes off if kept, and the best, freshest fish makes the best price.

So, as I said, ships and boats developed to match the purpose they were intended to fulfil. I suppose to some extent you could say the same for N.C.I. We were formed to save life at sea. That was our primary purpose even if we fulfil that by being just a small cog in the Emergency Service wheel. We watch, we log, we look for things which might go wrong. There are not many of us, we need more.

So, as I said, ships and boats developed to match the purpose they were intended to fulfil. I suppose to some extent you could say the same for N.C.I. We were formed to save life at sea. That was our primary purpose even if we fulfil that by being just a small cog in the Emergency Service wheel. We watch, we log, we look for things which might go wrong. There are not many of us, we need more.

It is not a difficult thing to learn, proper training is given. We are a friendly, sociable bunch of men and women. All we ask of you is that you can walk the cliff path to get to the Lookout at Pednvaden, that you have good eyesight and hearing, with glasses or aids if necessary, and that you can spare the time to keep at least two Watches a month. A watch is 2 ½ hours long but 3 hours in the school holidays. Add that to the time you will take to get from home to Rosevine and you can work out just what your commitment will be. We do need more people – there must be more of you retirees out there who can help – and those of you who are still working who can spare the time. Find out more by giving Sue a ring on 01872 530500 or Robert on 501670.

Pictures courtesy of Wikipedia