Time is of the Essence

My Longcase clock is messing about, stopping erratically every day. I have been poking about in the works to see if there is anything obviously wrong, so far without success. I have, however, found cause to marvel at the delicate intricacies of its intestines, so simple in principal but so complex in arrangement. Its measured ‘tick tock’ is counting away one’s life seconds as the song says, but I love it anyway. The earliest clocks were often built of iron by blacksmiths on the kitchen table when the long winter darkness restricted their time in the forge. Many had learned their craft on church clocks and it was a ‘paying hobby’, bringing in a little money when time got hard.

My Longcase clock is messing about, stopping erratically every day. I have been poking about in the works to see if there is anything obviously wrong, so far without success. I have, however, found cause to marvel at the delicate intricacies of its intestines, so simple in principal but so complex in arrangement. Its measured ‘tick tock’ is counting away one’s life seconds as the song says, but I love it anyway. The earliest clocks were often built of iron by blacksmiths on the kitchen table when the long winter darkness restricted their time in the forge. Many had learned their craft on church clocks and it was a ‘paying hobby’, bringing in a little money when time got hard.

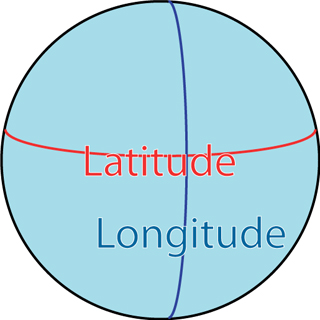

Whether we like it or not, for most of us our lives are ruled by time. It governs our daily routine, when we get up, when we have breakfast, hurrying to catch a train or bus. Time, in the form of days of the week, dictates our weekends. A watch or clock is an indispensible part of our personal equipment. This is even more so at sea, though modern electronics have made life easier. A ship going out of sight of land for more than a couple of days needs to know exactly where on the ocean it is. Of recent years the Global Positioning System, run by signals from satellites orbiting far above the Earth’s surface, gives a ship’s position at the touch of a button. Prior to the 1970’s this was not possible and in order to calculate the ship’s position a navigator had to establish its Longitude and Latitude,. producing a cross on a chart.

Finding ones latitude, the lines which run round the Earth, was easy and had been known to explorers since early Grecian times. The Equator is 0 degrees and latitude lines run parallel to that. They can be found by measuring the angle of a defined heavenly body, North Star, Sun or Moon, with the horizon. Instruments for doing this included the cross staff, a simple stick with a sliding cross piece and the astrolabe, a far more delicate instrument which looked like a wheel with a spoke across its width, pivoted on the centre axis.

Finding ones latitude, the lines which run round the Earth, was easy and had been known to explorers since early Grecian times. The Equator is 0 degrees and latitude lines run parallel to that. They can be found by measuring the angle of a defined heavenly body, North Star, Sun or Moon, with the horizon. Instruments for doing this included the cross staff, a simple stick with a sliding cross piece and the astrolabe, a far more delicate instrument which looked like a wheel with a spoke across its width, pivoted on the centre axis.

A ships instrument would be made of brass with an eyelet on the circumference by which it could be hung. The theory was that you used one hand to hang it in front of your face and the other hand to move the cross piece into line with the selected star. You then read off the degrees from the marked outer ring. Easy – until you tried hanging this pound or so weight with one hand at head height on the heaving deck of a ship! It was really a two man job, one to hold it and one to operate and read it. Nevertheless it remained in use for many centuries.

Longitude remained a problem. To get this it was necessary to fix the position of the sun in the sky at a set time of day and compare that with the time at a fixed point somewhere else on Earth – Greenwich in fact. To do this a ship would have to set a clock at Greenwich time when it left England and then measure the sun’s position at the same set time each day, noting the local time. The difference between the two times would give them Longitude, using a navigational table.

There was, however, no clock which could be relied upon to keep time. Most clocks of that day involved a pendulum with which a ship’s movement played havoc. The best idea they could come up with was a hour glass and it would fall to the duties of the ship’s boy to turn this over at the end of each watch. It was, at best, crude and, should he forget then all idea of accurate time could be forgotten.

There was, however, no clock which could be relied upon to keep time. Most clocks of that day involved a pendulum with which a ship’s movement played havoc. The best idea they could come up with was a hour glass and it would fall to the duties of the ship’s boy to turn this over at the end of each watch. It was, at best, crude and, should he forget then all idea of accurate time could be forgotten.

It was this problem which resulted in the wreck of Sir Cloudsley Shovel’s fleet on the Scilly Isles in 1707. This disaster finally pushed the British Government into passing the Longitude Act in 1714 which offered a reward of £20,000 for anyone who could solve the problem of keeping accurate time at sea. The timepiece would have to be tested over a period of months by a voyage to West Indies and back.

John Harrison who, believe it or not was a carpenter who made wooden clocks, spent years on the problem and, cutting a long story short, in 1735 produced a new type of instrument called a chronometer. It was successfully tested and copies were made. Look at the timescale! 1707 the wreck on the Scilly Isles, 1714 the Act was passed, and then, 21 years later the solution. The Government, however then started to try and wriggle out of their promises. Does that scenario sound familiar in some way? They prevaricated and demanded new tests, produced papers and had enquiries, all the usual sort of thing, anything to avoid paying up. In the end poor Harrison made a personal appeal to the Prime Minister in 1773 and was granted about £8000. He was in his eighties and the reward fell far short of what was promised

That instrument, copied thousands of times, became standard equipment on every ship in the world which travelled out of sight of land, and remained in general use until at least the 1970’s. Today ships use G.P.S. for navigation but chronometers are still carried as backup and Celestial Navigation is still part of a Master Mariner’s seagoing qualification. Today’s chronometers are digital and wireless controlled for extreme accuracy – but that can fail if the GPS signal is lost. You cannot beat good old reliable mechanics!

That instrument, copied thousands of times, became standard equipment on every ship in the world which travelled out of sight of land, and remained in general use until at least the 1970’s. Today ships use G.P.S. for navigation but chronometers are still carried as backup and Celestial Navigation is still part of a Master Mariner’s seagoing qualification. Today’s chronometers are digital and wireless controlled for extreme accuracy – but that can fail if the GPS signal is lost. You cannot beat good old reliable mechanics!

No one is going to ask one of our Watchkeepers to ‘shoot the sun’ or read the complicated Navigational Tables. Finding the exact position of an object in the water is still an essential part of our training. We do this by sighting along a pelorus which is fitted to our table and this gives us a directional bearing, so we can say that the object is somewhere along a line we draw on a chart. But distance along that line is important and here we have to make an informed judgement.

We know how far away are such points as Nare Head and Grebe Point and we have those distances permanently marked on our chart. With training and practice you find you can get a pretty accurate idea of how far out along the bearing line the object is. You can then mark the distance off on the line, make a cross, and, using the scales alongside the chart, give co-ordinates to Falmouth Coastguard. They can re-produce these on their chart so they can also see where the object is and, in turn, give a location to the Lifeboat or Helicopter should they be needed. You don’t need to have any experience or training to become a Watchkeeper.

We know how far away are such points as Nare Head and Grebe Point and we have those distances permanently marked on our chart. With training and practice you find you can get a pretty accurate idea of how far out along the bearing line the object is. You can then mark the distance off on the line, make a cross, and, using the scales alongside the chart, give co-ordinates to Falmouth Coastguard. They can re-produce these on their chart so they can also see where the object is and, in turn, give a location to the Lifeboat or Helicopter should they be needed. You don’t need to have any experience or training to become a Watchkeeper.

If you join us then ‘how to do it’ will be provided by our Training Team, and standing watch with experienced Watchkeepers will give you the practice. You will get all the friendly support you need and will not be left on your own until both you and our Tester are satisfied. It’s a good system and works well. We need more people, come and give us a try. Who to contact? Ring Robert on 01872-501670 or Bob on 580720

Thanks Malcom for taking the time to write this – very interesting. So many take GPS for granted these days but it is more fragile than many realise. Jon