A Quiet Coastline Does Not Mean Nothing Ever Happened

Last Saturday I sat in the Lookout on a clear sunlit day, with no wind and a flat sea. That alone was worth noting as so far this year it has been cold, grey and windy, the spray throwing salt on to the windows and the door shut to keep the temperature above freezing. This time, though, I looked at a sunlit Nare Head, unchanged in the last 78 years.

Last Saturday I sat in the Lookout on a clear sunlit day, with no wind and a flat sea. That alone was worth noting as so far this year it has been cold, grey and windy, the spray throwing salt on to the windows and the door shut to keep the temperature above freezing. This time, though, I looked at a sunlit Nare Head, unchanged in the last 78 years.

I was a small boy living in London at that time and, like most people remembering their childhood, the sun always seemed to shine. Grey windy skies don’t feature in distant memories. What I do remember, though, was looking up into the blue heavens and watching vapour trails etched across the sky, the distant snarl of engines, and the rattle of machine guns as our seniors tried to kill each other. It was 1940, the Battle of Britain was on, and the Nation fought for its life.

Those who lived in London or the big cities were in daily peril. Down in Cornwall, much as today, life was a little more sedate, but that did not mean complete escape from airborne danger. Plymouth and Falmouth were prime targets, a little too far for an organised daylight raid, but vulnerable in the hours of darkness. There were air attacks in 1940 but these became more intensified in 1941.

The authorities realised that Falmouth would be a prime target and took over Nare Head and Nare Point to build decoys. Ealing Studios erected dummy towns on each site complete with railways, roads, buildings and lights. They were opened in 1942 and manned by Royal Navy personnel. Lights were hidden in packing cases to simulate a poor blackout. Metal drums were filled with explosives and waste oil. If bombs were dropped the idea was to explode these to simulate bombing.

The last time they were used was 30th May 1944 during a heavy raid on Falmouth. It is known that on Nare Point on this occasion, nine bombs fell. Luckless navy crews were billeted at a farms nearby and it was their job to turn on the lights and encourage the enemy to bomb them! When the war ended the dummy towns were dismantled but poor Nare was not allowed to rest! A nuclear bunker was built in its place – still there and occasionally open to the public.

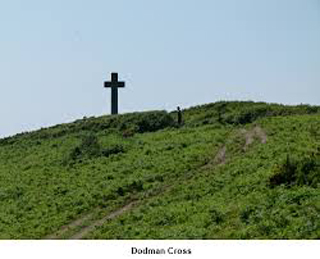

Further along the coast, almost hidden in haze, the great bulk of Dodman Point loomed. It’s the furthest north-eastern point we can see if you discount the rare glimpse of Rame Head on a clear day. The great cross on the top is often visible, erected in 1896 by Rev. George Martin, Rector of Caerhays, as a daymark to identify the point from the other minor headlands between St Anthony’s and Gribben Head. Apparently the Lord had reservations about the mark as it was struck by lightening the next winter and split in half. It has been repaired, the joint clearly visible, and now sports a lightening conductor.

Further along the coast, almost hidden in haze, the great bulk of Dodman Point loomed. It’s the furthest north-eastern point we can see if you discount the rare glimpse of Rame Head on a clear day. The great cross on the top is often visible, erected in 1896 by Rev. George Martin, Rector of Caerhays, as a daymark to identify the point from the other minor headlands between St Anthony’s and Gribben Head. Apparently the Lord had reservations about the mark as it was struck by lightening the next winter and split in half. It has been repaired, the joint clearly visible, and now sports a lightening conductor.

The daymark did not save three Royal Navy torpedo boat destroyers the year after it was erected . In September of that year the ships were making their way along the coast in poor visibility. The commander of the lead ship, Sunfish, suddenly saw land in the gloom ahead and was in time to hastily reverse and get out of danger. Lynx and Thrasher were not so lucky and both went aground.

Lynx managed to free herself and make for repairs at Plymouth but Thrasher was badly damaged. She fractured a steam pipe and three men died in the engine room when steam was released at full pressure. Incidentally, in 1910, Thrasher’s sister ship, Quail, hit the Flushing trawler Olivia at 21 knots off Porthallow, cutting her in half. Four of the five fishermen on board died.

The days of sail made the Cornish coast into a graveyard of ships. Sticking out as it does it was often the first point of land that a vessel would encounter on its way to Europe, an obstruction in their path which was difficult to avoid. Vessels transiting from east to west English ports had to go round it.

The situation was not helped by the establishment of the Lloyd’s Signal Station on the Lizard as it was common practice for ships travelling from far afield to head to ‘Lands End for Orders’. The journeys took so long that the market had often changed between loading in Australia and discharging in Europe so cargo owners would wait until the ship was a few days away before giving them their discharge port. This is what happened to our most famous local wreck, the ‘Hera’. She arrived near Cornwall in poor visibility and got lost.

The situation was not helped by the establishment of the Lloyd’s Signal Station on the Lizard as it was common practice for ships travelling from far afield to head to ‘Lands End for Orders’. The journeys took so long that the market had often changed between loading in Australia and discharging in Europe so cargo owners would wait until the ship was a few days away before giving them their discharge port. This is what happened to our most famous local wreck, the ‘Hera’. She arrived near Cornwall in poor visibility and got lost.

Four shipwrecks stand out for great loss of life. In January 1809, in a snowstorm, the Navy Brig ‘Primrose’ ran onto the Manacles. She carried a crew of 127 out of which the only survivor was a drummer boy. Then in 1855 and emigrant ship, the ‘John’ ran onto the same rocks at half tide on 10th May in a violent storm.

The impact stove her bottom in but she came free of the rock and the Captain elected to run her ashore. She stopped again 200 yards out. She was carrying 210 emigrants for America and a crew of 77 and all gathered on deck to await rescue. But the rising tide gradually engulfed the waiting survivors, the waves washing all off into the surf where over 120 drowned. A little footnote to the report says that those who survived got their fare money back!

One of the most baffling of events was the wreck of the ‘Mohegan’ a large steamship carrying passengers and cattle on the way to New York. On 14th October, 1898, she passed Eddystone, unusually leaving it to port. Some of the people on board apparently noticed that the course was wrong but no one questioned it. The effect was that instead of passing Lizard safely to starboard she arrived off the Helford river, turned sharply south and ploughed into the Manacles at full speed, just as daylight was failing.

The ship sank within twenty minutes, only her masts and funnel showing above water. Efforts to reach survivors were handicapped because no one on shore knew exactly where she was in the darkness. She had been carrying 161 people of which only 44 were saved though varying reports give different figures. The cause of the accident remains a mystery. Every officer died in the sinking. Was there a faulty compass or a navigational error?

The ship sank within twenty minutes, only her masts and funnel showing above water. Efforts to reach survivors were handicapped because no one on shore knew exactly where she was in the darkness. She had been carrying 161 people of which only 44 were saved though varying reports give different figures. The cause of the accident remains a mystery. Every officer died in the sinking. Was there a faulty compass or a navigational error?

There is mass grave in St Keverne Churchyard and a magnificent stained glass window above the Church altar.

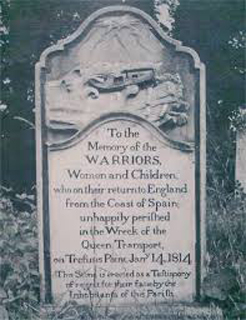

The largest casualty figure in our area is even more bizarre as it occurred within the shelter of Falmouth Harbour. In December 1813 the brig ‘Queen’ was returning to Portsmouth carrying soldiers and their families at the end of the Peninsular War. An easterly gale sprang up and she went in to Falmouth for shelter, anchoring in Carrick Roads. For some reason, despite the strong easterly gale blowing straight into the harbour, the Captain only laid one anchor on a short scope.

The ship stayed there for three days but then started to drag. Apparently no one noticed until too late and the ship, gathering speed, smashed onto the rocks of Trefusis Point. Waves began to break over her. In the confusion attempts were made to fire a cannon as a distress signal but the sea swamped the cannons and by now heavy snow was falling making it almost impossible for anyone to see the wreck from the shore.

The Captain ordered all the masts to be cut away, and as they fell the ship gave a sickening lurch which caused guns to be cast adrift and bulkheads to break. As the hull gave way, all below were either crushed to death or drowned. In less than twenty minutes of striking Trefusis Point the Queen had been reduced to matchwood. Over 200, some accounts say 250, people died, and there is a memorial on Mylor Churchyard. For those who wish to read it there is a fascinating account of the incident on Google if you search ’Wreck of the Queen’ and then ‘A Quaker Record’.

The Captain ordered all the masts to be cut away, and as they fell the ship gave a sickening lurch which caused guns to be cast adrift and bulkheads to break. As the hull gave way, all below were either crushed to death or drowned. In less than twenty minutes of striking Trefusis Point the Queen had been reduced to matchwood. Over 200, some accounts say 250, people died, and there is a memorial on Mylor Churchyard. For those who wish to read it there is a fascinating account of the incident on Google if you search ’Wreck of the Queen’ and then ‘A Quaker Record’.

Reading this rather gloomy account of death and destruction which has taken place within a few miles of our Lookout we must be thankful that steady technical achievements have made it unlikely that such carnage will come our way. Firstly steam propulsion, then motorised engines, solved the often fatal consequences of being ‘embayed’. Then radio made getting assistance easier.

Satellite Navigation and Radar has taken the guesswork out of navigation in poor visibility and now we have Digital Selective Calling (DSC) which sends a distress call with full details at the touch of a button. We now have help from the air as well from the Coastguard helicopter. Making use of all this technology the Emergency Services can get help to a casualty rapidly and efficiently, making a successful rescue far more likely. Things still go wrong of course.

Electronics fail, watch keeping on a ship is sometimes reduced to a couple of men who take turns to sleep, shipmasters wait too long before letting the Coastguard know they have a problem, floating hazards like containers are common and difficult to see – the list is endless. Then there are the over confident, the careless and the unlucky – which is where we of the National Coastwatch come in as most of these incidents happen in shallow waters used by the ‘leisure industry’ – the recreational water user.

This coming season we must expect the small motor craft to run out of fuel, the tired paddle boarder to be unable to right his craft, the rubber dinghy or toy to blow seawards when Dad relaxes his watch. On land we may have the heart attack on the beach, the broken arm in fall on the Coast Path, or the child slip on the rocks and get a nasty cut. This is our ‘bread and butter’. We are trying to cover watches every day but really do need a few more volunteers to fill the gaps of the holiday season. You can help. The usual plea with the usual telephone numbers – Sue on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681

This coming season we must expect the small motor craft to run out of fuel, the tired paddle boarder to be unable to right his craft, the rubber dinghy or toy to blow seawards when Dad relaxes his watch. On land we may have the heart attack on the beach, the broken arm in fall on the Coast Path, or the child slip on the rocks and get a nasty cut. This is our ‘bread and butter’. We are trying to cover watches every day but really do need a few more volunteers to fill the gaps of the holiday season. You can help. The usual plea with the usual telephone numbers – Sue on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681

Pictures Courtesy of Wikipedia and own collection

This is such an interesting article, Malcolm. I enjoyed reading it to your heartfelt last paragraph.