Viking, Forties, North Utsire…

This year is the 150th birthday of the Met. Office, believed to be the provider of the longest running continual forecast in the world. The first forecast was issued in 1859 but it was 1867 before the shipping forecast became a regular event.

It all began with Admiral Fitzroy, the man who had captained the Beagle during Darwin’s world voyage of exploration. He was only 23 at this time and it was his first command. He had been working with Francis Beaufort, (he of the Wind Scale), training in meteorology. Darwin had left in HMS Beagle on his first voyage of discovery and was in Patagonia when his captain, in a fit of depression, committed suicide. Beaufort recommended Fitzroy to be his successor and he commanded Beagle for the completion of the first voyage and the whole of the second.

He became an MP and then accepted the Governorship of New Zealand, which proved a poisoned challis. Frustrated, disillusioned and a poor diplomat he was recalled after two years, arriving back in London, still in the Royal Navy but with no definite task to fulfil. He drifted from post to post, he undertook an unsuccessful voyage in the first screw driven warship, gave that up and returned to London.

His wife died suddenly and he lapsed into despair. He shook himself out of that and went to the Admiralty in 1854 with a completely new idea – to found an office for meteorology. The original idea was the production of charts but he expanded this into predicting the weather and providing an occasional service for shipping, published in ‘The Times’, which he called ‘forecasting’. The novel idea caused much amusement and Punch christened him ‘First Admiral of the Blew’. In 1857 he formally established the Met Office, and started a campaign to provide publicly available barometers at most of the ports around the country.

Then, in 1859, events took place which shook the maritime world. On the night of 24th October the steam clipper Royal Charter left Queenstown, which is now Cork, heading for Liverpool. She was one of the fastest ships in the world and had left Australia only 59 days earlier. Among the passengers were many miners returning home from the goldfields and the holds were full of boxes of gold, each labelled with a passengers name. In addition many carried gold on their person, in pockets or sewn into their clothes. She was a ship of fabulous wealth, in today’s terms many millions of pounds.

A storm was brewing in the north Irish Sea and, as the ship approached the Welsh coast and turned the corner of Anglesey the full blast of the wind hit them. To begin with it was easterly, a headwind, but it soon swung to the north, full on the beam, with the Anglesey coast just three miles to leeward. The wind rose to 100mph gusts and the ships rudder failed. Captain Taylor ordered the two anchors dropped to try and ride out the gale but first one cable snapped and then the other.

A storm was brewing in the north Irish Sea and, as the ship approached the Welsh coast and turned the corner of Anglesey the full blast of the wind hit them. To begin with it was easterly, a headwind, but it soon swung to the north, full on the beam, with the Anglesey coast just three miles to leeward. The wind rose to 100mph gusts and the ships rudder failed. Captain Taylor ordered the two anchors dropped to try and ride out the gale but first one cable snapped and then the other.

Driven sideways she was forced onto the sand, about 25 yards from the shore. Her plight had been seen and the villagers from Moelfre turned out to help. A brave seaman on the ship volunteered to try to swim a line ashore, which he did, and some of the passengers were rescued. But the tide was rising and lifted the ship, at that stage unbroken, and pushed her onto the rocks, where she broke up. Too deep for a man to stand up the waves pounded the wreck and only a handful was saved. In all only 40 of the 490 passengers were saved.

She was not the only ship to come to grief that night. Around the country 133 ships were lost and another 90 damaged. 800 lives were lost. Something had to be done and the Press, sceptics in the past, were at the forefront of the clamour for a solution. Attention turned to the Met Office and Fitzroy expanded his activities, setting up fifteen land stations around the coastline, which, using the new telegraph, would provide him with weather readings.

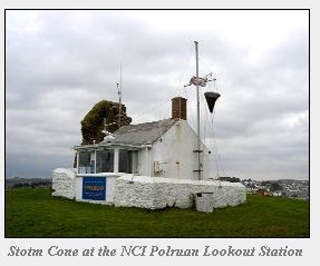

He then created a system by which cones could be hoisted at ports around the country to give warnings of gales, upward pointed to indicate a northerly gale and downward to indicate south. To back this up he introduced a legal requirement that ships were not to leave harbour in these conditions. This proved very unpopular with the owners of fishing fleets who felt that their skippers were quite capable of dealing with adverse conditions and, under their pressure, the idea was abandoned after Fitzroy’s death. The skippers themselves, however, were all in favour of the idea and the hoisting of cones was re-introduced in 1872 though without the mandatory requirement to stay in port.

He then created a system by which cones could be hoisted at ports around the country to give warnings of gales, upward pointed to indicate a northerly gale and downward to indicate south. To back this up he introduced a legal requirement that ships were not to leave harbour in these conditions. This proved very unpopular with the owners of fishing fleets who felt that their skippers were quite capable of dealing with adverse conditions and, under their pressure, the idea was abandoned after Fitzroy’s death. The skippers themselves, however, were all in favour of the idea and the hoisting of cones was re-introduced in 1872 though without the mandatory requirement to stay in port.

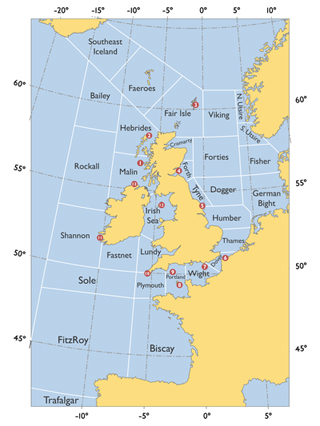

Throughout all this time the Met. Office was going from strength to strength, by now well established as a primary source of weather information at sea. The first ‘B.B.C.’ radio broadcasts were in 1920 and the first broadcast Shipping Forecast was made in 1921. Apart from a break during the Second World War it has gone out every day since then. The area from South East Iceland to Trafalgar in Northern Spain and across to the German Bight is divided into 31 forecast areas. There have been a few name changes over the years but not many. In general they are called after geographical features such as sand banks and islands but Fitzroy himself is honoured in being given his own area out to the west of the Bay of Biscay.

Sometime in the 1960’s the Met Office decided that, with the increase of leisure sailing, there was a need to be more specific in forecasts for the amateur sailor. Sea area Plymouth for example covers from Isles of Scilly to Portland Bill and southwards to the coast of France. That is one of the smaller ones! Most leisure sailors are within ten miles of the shore for much of the time so it was decided that a new Inshore Forecast would be introduced covering up to 12 miles offshore. That is what we hear today and our area is Lyme Regis to Lands end including the Isles of Scilly.

Sometime in the 1960’s the Met Office decided that, with the increase of leisure sailing, there was a need to be more specific in forecasts for the amateur sailor. Sea area Plymouth for example covers from Isles of Scilly to Portland Bill and southwards to the coast of France. That is one of the smaller ones! Most leisure sailors are within ten miles of the shore for much of the time so it was decided that a new Inshore Forecast would be introduced covering up to 12 miles offshore. That is what we hear today and our area is Lyme Regis to Lands end including the Isles of Scilly.

It would be simpler to call it Lyme Regis to Isles of Scilly! But, for our purpose, it is ideal and gives us a good idea about what to expect in the next twelve hours. The Met. Office issues its forecasts at 2300hrs, 0500hrs, 1100hrs and 1700hrs UTC. Each one covers a period starting one hour later. This is re-broadcast by the Coastguard at three hourly intervals, updated as necessary. UTC is ‘Co-ordinated Universal Time’. For some reason someone decided that the true mnemonic should not be used – that would be CUT! UTC is not a time zone but a time system but we do not need to go down that complicated alley. For all practical purposes normal human beings can regard UTC as the same as Greenwich Mean Time.

We have come a long way from Admiral Fitzroy’s idea of a forecast for sailors. Technology obviously plays a huge part but the information it gathers must still be translated into something which is understandable by the ordinary man. In my time I have listened to countless forecasts, Inshore and Offshore, and given due weight to what I hear. No doubt there have been many occasions when I missed out on a good sail by being too cautious but better that than be a customer of the RNLI.

We always tried to hear the 0048hrs forecast, usually preceded by ‘Sailing By’, a light orchestral piece by Ronald Bynge, a placid, calming piece often not in keeping with what is to come. I recall sitting gale bound in Loch Swilly on the north coast of Ireland one summer, the wind whistling in the rigging and the boat tugging at its anchor chain, praying for some relief from the relentless wind. We had been there, alone, for a couple of days before being joined by a Trans-Atlantic yacht, a single-handed lady who, no doubt, gave a sigh of relief at the somewhat dubious shelter. We were there another two days, running short of food, before things eased enough to replenish stocks. Looking back on it now I must be thankful to Admiral Fitzroy. But for him and the Met Office it might have been us smashed on an unforgiving coastline!

In our Lookout we try to record the latest weather forecast and put it on show for our land based passers by. Because of the peculiarities of Radio Law and OFCOM we are not allowed to relay the current forecast to any passing yachtsman using our Channel 65, though we can tell him what the weather is actually doing at the present in Gerrans Bay. He probably knows that in any case as to speak to us he has to be at sea and not very far away! Perhaps, in the future, this anomaly will be sorted out but, for the time being, we can only give him the current Inshore Forecast if the Coastguard tells him they are too busy to do so. It is just another of the useful things that our Watchkeepers can do towards safety at sea.

A few more Watchkeepers would be useful. Try ringing Sue on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681 to see if you can help.