Nicci French’s website refers to “one of the world’s leading crime fiction writers”. Not quite true – Nicci French is actually two writers – Nicci Gerrard and her husband, Sean French.

Nicci French’s website refers to “one of the world’s leading crime fiction writers”. Not quite true – Nicci French is actually two writers – Nicci Gerrard and her husband, Sean French.

Like many families, they have links to Cornwall, where Nicci’s sister lives. They spend family holidays walking nearby, often along the coastal path, and are keen sailors. Nicci has sailed from childhood. Unfortunately, Sean has something in common with Lord Nelson; he is sick every time he goes to sea.

To the obvious question – what first gave them the idea of writing together?

“When we met we were both journalists and were always each other’s first editors, showing each other articles we’d written before delivering them. So, shared writing – and reading – was part of our relationship from the beginning. We started talking about collaborating one day, then stumbled on a subject – the controversy about therapy patients ‘recovering’ memories of sexual abuse – we thought would work as a thriller. And since we’d come across the idea together, it seemed like the right time.

We wrote our first books in a busy family household, four children, pets, mess, and never enough time. ‘Blue Monday’, the first in the Frieda Klein series, was written as our youngest child was finishing school. Somehow, and in ways that are not always easy to explain, our stories have always seemed part of our family life.”

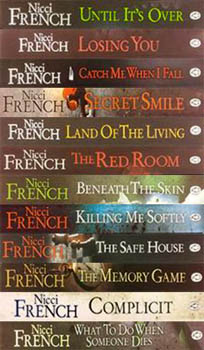

I wondered at what point they knew it would work. “We began our first book, ‘The Memory Game’, almost as an experiment to see whether we could write together. About half way through we got a sense that it was developing a life of its own. But there was still the question of how other people would respond to it – whether we could get away with writing as one person. Then as people started to read the book, Nicci French took on a life of her own and she’s never gone away.

I wondered at what point they knew it would work. “We began our first book, ‘The Memory Game’, almost as an experiment to see whether we could write together. About half way through we got a sense that it was developing a life of its own. But there was still the question of how other people would respond to it – whether we could get away with writing as one person. Then as people started to read the book, Nicci French took on a life of her own and she’s never gone away.

We’ve met a few [other people who write together] and read about others, but we’ve never heard of anyone who works quite like us. Usually, probably sensibly, literary couples divide the work. One might write the more procedural sections, for example. Sometimes one of the couple does all the actual writing. Our method is much messier. We both do research but never decide in advance who will write which bit. One person will write, say, a chapter, pass it to the other, who can edit, rewrite, or even, sometimes, just leave it alone. It’s time-consuming and complicated, but it works for us.

We spend a lot of time talking about ideas, story and characters, in advance. If we have a real disagreement about something important, that’s usually a sign one of us isn’t completely sold on the idea or that we don’t have the same book in our heads. Dealing with that sometimes involves junking the idea entirely. But we won’t start writing a book until we’re sure we’re committed to the same idea.”

Do you need a trigger to start writing/to give you an idea?

“We’re always open to ideas, always talking about and testing them, having ‘what-if’ discussions. But you can’t really go looking for an idea; you have to wait for it to come to you. At the same time, you have to create the right climate for an idea to come. We read a lot in areas that interest us, we go to places that might set us off, we talk to people. The trigger to start writing is different. You can plan and research for ever, but at a certain point, you have to say, enough is enough and get going.

People sometimes ask for advice about writing. What we mainly say is this: if you want to write, then you must simply get down and write. Treat it as seriously as any other job. What the finest writers have, apart from their talent, is a capacity for hard, sustained and lonely work. Just as important is to read and read and read. And if you want, say, to write thrillers, read thrillers, but don’t just read thrillers, read a range of fiction and non-fiction. Think about what you like about them, what you don’t like. Books you don’t like can be as useful as those you do. If a thriller didn’t work for you, why didn’t it work? How would you have fixed it?

People sometimes ask for advice about writing. What we mainly say is this: if you want to write, then you must simply get down and write. Treat it as seriously as any other job. What the finest writers have, apart from their talent, is a capacity for hard, sustained and lonely work. Just as important is to read and read and read. And if you want, say, to write thrillers, read thrillers, but don’t just read thrillers, read a range of fiction and non-fiction. Think about what you like about them, what you don’t like. Books you don’t like can be as useful as those you do. If a thriller didn’t work for you, why didn’t it work? How would you have fixed it?

As to reviews, the problem is that it’s a bit like visiting a doctor for a diagnosis of an illness you had three years ago. By the time you get helpful criticism, you’re deep into your next book – or the one after that. On the other hand, it’s always fascinating to meet readers and hear their thoughts on the books. Often they respond to stories and characters in ways you never anticipated. We always learn from these encounters, whether from readers in bookshops, literary festivals or prisons.”

How long does it take for a book to percolate?

“It depends on the idea. We had the idea for ‘Killing Me Softly’ while we were writing another book. We were so grabbed by it that we scrapped that book and wrote KMS instantly and quickly. We were haunted by the initial idea for ‘Land of the Living’ (a woman wakes in the dark, doesn’t know where she is or how she got there) for several years before we thought of the story to attach it to.”

What are you working on now?

“We’re currently deep in a sequence of novels featuring the analyst, Frieda Klein, who, quite against her wishes, finds herself involves in the world of crime investigation. ‘Tuesday’s Gone’ (the second in the sequence, reviewed elsewhere on Roseland online) has just come out in paperback, ‘Waiting for Wednesday’ comes out soon, and we’re now deep into Thursday. When we’re finished, we’ll have spent almost a decade in the life of this difficult, complicated and – for us – captivating woman. It’s come to feel like a very intimate relationship.”

“We’re currently deep in a sequence of novels featuring the analyst, Frieda Klein, who, quite against her wishes, finds herself involves in the world of crime investigation. ‘Tuesday’s Gone’ (the second in the sequence, reviewed elsewhere on Roseland online) has just come out in paperback, ‘Waiting for Wednesday’ comes out soon, and we’re now deep into Thursday. When we’re finished, we’ll have spent almost a decade in the life of this difficult, complicated and – for us – captivating woman. It’s come to feel like a very intimate relationship.”

And finally, what do they think is their target audience. “Maybe our target audience is ourselves. We write books we would want to read ourselves.” It works for me.