We Have Come a Long Way From a Blown Up Pig’s Bladder

Having had to give up sailing at sea about four years ago I turned to a narrow boat – 42ft long and only 7ft wide. It’s a bit like living in a corridor, but it is a boat, so much of the years of experience is still needed. The hardest thing to get used to was that this is described as ‘a contact sport’. With sea going boats you spend huge effort in not hitting anything else. With narrow boats the opposite applies – you do not seek to hit anything but it is a hazard of everyday life. These vessels are built of steel and are tough, a reminder of their heritage as carriers of goods in confined waters where packing them tightly together was a necessary part of loading and unloading.

Having had to give up sailing at sea about four years ago I turned to a narrow boat – 42ft long and only 7ft wide. It’s a bit like living in a corridor, but it is a boat, so much of the years of experience is still needed. The hardest thing to get used to was that this is described as ‘a contact sport’. With sea going boats you spend huge effort in not hitting anything else. With narrow boats the opposite applies – you do not seek to hit anything but it is a hazard of everyday life. These vessels are built of steel and are tough, a reminder of their heritage as carriers of goods in confined waters where packing them tightly together was a necessary part of loading and unloading.

There are not so many lock keepers now as there used to be and many of the old lock-keepers cottages stand derelict or have been sold off as second homes. Some remain though and are supplemented by volunteers who give up their spare time to helping holiday makers through the locks. While recently away on the boat I was struck by the fact that every lock keeper and every volunteer wears a life jacket while working. It is a mandatory condition of employment. Very few boaters do, no doubt lulled into a sense of security by the placid water on which they travel: no waves, very little current, and more often than not, sheltered from the wind.

The canal is, on average, only about four feet deep, so if you fall over the side you can walk ashore. The bank is seldom more than 20 feet away and is usually climbable. What need is there for a life jacket? Then you see the difference at the locks. Water pouring in and out under immense pressure, 20 ton boats being pushed around like child’s toys in a bath, perhaps 30ft of water surging and eddying, you would stand little chance if you fell in. Hence the rules and regulations – life jackets are as important here as on a yacht beating into the wind across Veryan Bay or the man in the kayak fighting his way back around Pednavaden Point against the wind and waves.

The canal is, on average, only about four feet deep, so if you fall over the side you can walk ashore. The bank is seldom more than 20 feet away and is usually climbable. What need is there for a life jacket? Then you see the difference at the locks. Water pouring in and out under immense pressure, 20 ton boats being pushed around like child’s toys in a bath, perhaps 30ft of water surging and eddying, you would stand little chance if you fell in. Hence the rules and regulations – life jackets are as important here as on a yacht beating into the wind across Veryan Bay or the man in the kayak fighting his way back around Pednavaden Point against the wind and waves.

It seems likely that the use of some form of flotation device to help people in the water was known as early as 500BC, though not so much as life savers but as a means of crossing water using inflated animal skins. Though in 1757 an unknown Frenchman made a flotation device for use in emergency the idea did not take off and it was not until 1765 that any serious effort was pursued to save life at sea. Few early sailors could swim – many regarded it as a disadvantage, it was a means of keeping you afloat longer when there was little chance of rescue – better to get it over quickly. Then Dr John Wilkinson made a study of the problem and concluded that, of the 4,000 British seamen drowned each year, about 1,000 could have been saved if there had been some way of keeping themselves afloat. He designed the first practical life jacket, a cumbersome thing made of cork which he patented.

There was still little interest in developing a practical jacket. The idea was even discouraged in the British Navy as it would assist pressed seamen to get ashore if they jumped off a vessel in harbour, and conditions on many merchant vessels were so bad that the inexperienced ‘seaman’ might decide life was better ashore. In 1813 though a interesting experiment took place in Falmouth and is described in the ‘West Briton’ newspaper as ‘a seaman’s bed and a life preserver’. It was essentially a mattress with a hole in the centre. This hole could be filled with a cushion when sleeping, or the cushion could be removed and a head put through the hole to transform it into a lifejacket; the removed cushion serving as a cap to protect the wearer. It was, however, yet another idea to fall by the wayside.

There was still little interest in developing a practical jacket. The idea was even discouraged in the British Navy as it would assist pressed seamen to get ashore if they jumped off a vessel in harbour, and conditions on many merchant vessels were so bad that the inexperienced ‘seaman’ might decide life was better ashore. In 1813 though a interesting experiment took place in Falmouth and is described in the ‘West Briton’ newspaper as ‘a seaman’s bed and a life preserver’. It was essentially a mattress with a hole in the centre. This hole could be filled with a cushion when sleeping, or the cushion could be removed and a head put through the hole to transform it into a lifejacket; the removed cushion serving as a cap to protect the wearer. It was, however, yet another idea to fall by the wayside.

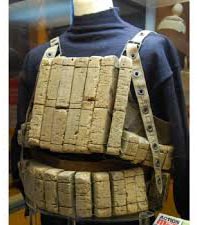

Forty years went by before the fore runner of the present life jacket was designed in 1854 by Capt John Ward, an RNLI inspector, who was looking for better protection for his crews. Once again cork was to provide the buoyancy but this was sewn loosely inside a canvas vest, thus giving flexibility to allow rowing or swimming. It was so successful that the RNLI sold chest loads of them to merchant ships at low prices. The jacket really proved its worth when the Whitby lifeboat capsized in 1861 and the only survivor from the crew of 13 was a young man who was the only one wearing the new life jacket.

Cork, however, is cumbersome to wear and does not bend. It also has the disadvantage that, if someone jumped from any height off a ship, when they hit the water the rigidity of cork and its inherent buoyancy could break the neck of the jumper when the life jacket stopped on hitting the water but the person’s body kept on going! To get round this problem in the early 1900’s they experimented with kapok, a fibrous vegetable wool which had high water resistance. This jacket became known as the ‘Mae West’. A person wearing one appeared physically well endowed as was the actress! Even then it had its disadvantages. As a wool it slowly became saturated and, after many hours, would become more of a liability than a help, so, if rescue was not at hand within that time, the wearer could be turned onto their face, bearing in mind that the buoyancy was carried on the wearer’s chest. Many men drowned like that.

Cork, however, is cumbersome to wear and does not bend. It also has the disadvantage that, if someone jumped from any height off a ship, when they hit the water the rigidity of cork and its inherent buoyancy could break the neck of the jumper when the life jacket stopped on hitting the water but the person’s body kept on going! To get round this problem in the early 1900’s they experimented with kapok, a fibrous vegetable wool which had high water resistance. This jacket became known as the ‘Mae West’. A person wearing one appeared physically well endowed as was the actress! Even then it had its disadvantages. As a wool it slowly became saturated and, after many hours, would become more of a liability than a help, so, if rescue was not at hand within that time, the wearer could be turned onto their face, bearing in mind that the buoyancy was carried on the wearer’s chest. Many men drowned like that.

The Second World War accelerated many inventions and brought about the development of the successful jacket that we see today. The need for something lightweight that allowed the wearer to go about their normal duties, which could be folded up and worn in an aircraft cockpit, and the development of water and air proof materials allowed air under pressure to be used – even air blown into it by the wearer.

Now the life jacket is a common sight – but not, in the view of RNLI, common enough. Each season we conduct a survey, on their behalf, of the numbers of water users visible from the Lookout who are wearing life jackets while using kayaks, boards and boats. It cannot be a comprehensive survey as often a boat may be visible but the occupants not in full view. Many of what I call ‘contact water users’, such as paddle boarders and wind surfers, wear wet suits and imagine they will do the job.

Now the life jacket is a common sight – but not, in the view of RNLI, common enough. Each season we conduct a survey, on their behalf, of the numbers of water users visible from the Lookout who are wearing life jackets while using kayaks, boards and boats. It cannot be a comprehensive survey as often a boat may be visible but the occupants not in full view. Many of what I call ‘contact water users’, such as paddle boarders and wind surfers, wear wet suits and imagine they will do the job.

As I understand it from talking to experienced friends, a wet suit will help but can never replace a life jacket so even these people should be wearing one. Some do – some don’t. It is pleasing to see the numbers of kayakers who wear jackets, even if they have a wetsuit. They are far more vulnerable than the boarders as, if you ride a board of any sort, you expect to fall off and are skilled in re-mounting. While I like to think all kayakers are trained in ‘re-mounts’ I do wonder just how often they practice this and how good they are.. I am told, never having done it, that it is a difficult and tiring exercise if you do not get it right first time. We see hundreds of kayaks – what proportion of the crew are expert?

Dinghy sailors need life jackets at all times – and, to be fair, most wear them. Rubber boats and RHIBs? RNLI statistics will show you that the biggest single cause of falling in the water comes from small tenders, the mini-sized inflatables yachtsmen use to get to and from their boats. It’s not while actually in the boat but while getting in or out. Falling in in Portscatho Bay in the early evening on your way to the pub is annoying, embarrassing and the splash and commotion might alert our Watch Keeper. Falling in on your way back in the dark with three pints of local ale sloshing about could be fatal. There is no one in the Lookout to raise an alarm, other boats may be asleep, and I can tell you from experience it is extremely difficult to climb up the side of a yacht from water level.

Dinghy sailors need life jackets at all times – and, to be fair, most wear them. Rubber boats and RHIBs? RNLI statistics will show you that the biggest single cause of falling in the water comes from small tenders, the mini-sized inflatables yachtsmen use to get to and from their boats. It’s not while actually in the boat but while getting in or out. Falling in in Portscatho Bay in the early evening on your way to the pub is annoying, embarrassing and the splash and commotion might alert our Watch Keeper. Falling in on your way back in the dark with three pints of local ale sloshing about could be fatal. There is no one in the Lookout to raise an alarm, other boats may be asleep, and I can tell you from experience it is extremely difficult to climb up the side of a yacht from water level.

Larger boats under way or crew simply sitting in the cockpit at anchor? Personally I never did except at night or in poor conditions. It is far more important not to go overboard in the first place, so a proper life line, securely attached is far better. Every outdoor sport has an element of risk. The important thing is to recognise that and take appropriate steps to minimise it.

As an organisation, the National Coastwatch fully supports the RNLI in their campaign to make all water users aware of the possible dangers. A good life jacket costs about £60 – your funeral costs will run into thousands, not to mention the grief it will bring on your family. Oh, and by the way. Should the worst happen and you fall in the water no one is going to help if no one has seen you. That is the importance of our Lookout, perched high on Pednavaden Point, a bird’s eye view of what is happening on the water. Our chances of seeing you are far greater than your wife on the beach. Our telephone to the Coastguard is a much better way of getting help than have her run around shouting. But we do need more volunteers. Find out what you can do to help by ringing Bob on 01872-580720 or Robert on 501670

As an organisation, the National Coastwatch fully supports the RNLI in their campaign to make all water users aware of the possible dangers. A good life jacket costs about £60 – your funeral costs will run into thousands, not to mention the grief it will bring on your family. Oh, and by the way. Should the worst happen and you fall in the water no one is going to help if no one has seen you. That is the importance of our Lookout, perched high on Pednavaden Point, a bird’s eye view of what is happening on the water. Our chances of seeing you are far greater than your wife on the beach. Our telephone to the Coastguard is a much better way of getting help than have her run around shouting. But we do need more volunteers. Find out what you can do to help by ringing Bob on 01872-580720 or Robert on 501670