So Autumn is upon us in earnest. We appear to have gone from (perpetual) Summer to Autumn overnight! The bees are carrying on regardless, however, and though the beekeeping season is nearly over there is still lots to be done. The ivy is in full flow at the moment and the smell of the ivy nectar being converted to honey as you walk among the hives is magical!

It’s not a moment too soon, either, as I’ve been checking the food situation in my hives and whilst the majority are in a reasonable state of provision for the winter, a small number are really struggling to bring anything in. This is because, when the nectar dried up during the summer and there was no food coming into the hive, the bees stopped the queen from laying eggs.

This resulted in a check in colony development and bee numbers dropped, so the number of young bees was reduced meaning that bees that were old enough to be foragers had to stay home and tend whatever new brood the queen had been able to lay. Consequently, the stores situation started to suffer and though honey bees are purported to be intelligent though instinctive creatures, sometimes they can’t see the folly of the path they are taking.

Thanks to Storch (“At the Hive Entrance”), I found two of my colonies in particular were in this situation, both late swarms (actually casts, so without a laying queen) and small in numbers to begin with. Neither had any stores whatsoever – they were living hand-to-mouth on whatever was being brought in by the foragers!

Thanks to Storch (“At the Hive Entrance”), I found two of my colonies in particular were in this situation, both late swarms (actually casts, so without a laying queen) and small in numbers to begin with. Neither had any stores whatsoever – they were living hand-to-mouth on whatever was being brought in by the foragers!

This necessarily resulted in some bees dying prematurely, so reducing the colony size even further. Whilst I found the queen in one of them, the other appeared not to have a queen – yet there were two supercedure cells slap bang in the middle of a comb! Supercedure cells are built by the bees when they feel their queen is failing and she needs to be replaced, so they create one (or two at most) queen cells and, once the virgin queen has emerged, she and the mated laying queen will live together in the hive, being kept apart by the bees so that one is not killed by the other.

Once the virgin has mated she will start to lay eggs and the two queens will continue to lay eggs in the hive until the bees think the new queen has proved herself – and they then kick out the old queen! But there were no eggs, no open brood and no sealed brood. So where did the bees find the larvae to enable them to create queen cells? There must have been a queen in the hive somewhere, but I just couldn’t see her! I took emergency action on seeing the stores situation though and sprayed 1:1 sugar solution into the empty combs and placed a block of fondant on the bottom bars of two frames that had not been fully drawn. Within minutes the bees were out foraging again in sensible numbers and they lived to see another day.

When I checked on the hive again a couple of weeks later, there were eggs, open brood and sealed brood – and one hatched queen cell! The hatched queen couldn’t have laid the eggs herself as the time-scale didn’t allow for that, so there was a queen in the hive all along and the bees just thought that, since there was no brood, she must have been failing, so they took steps to replace her! I saw the hatched virgin – time will tell whether she is able to mate or not as there are not many drones around at this time of year and the weather generally is not suitable for queen mating to take place – but we’ll see! If she doesn’t mate, the bees will kick her out and things will just carry on as normal.

The other colony I noticed that wasn’t foraging as actively as I would expect turned out to have the same problem – no stores, no eggs, no open brood, but there was sealed brood and the queen was on it. I fed them, exactly as I had the other colony, and again, within minutes, the foragers were out and doing what was necessary. I need to check this colony shortly as well, just to make sure everything is as it should be inside, but I’ve seen pollen going into the hive and the foragers are very active. I’m very hopeful!

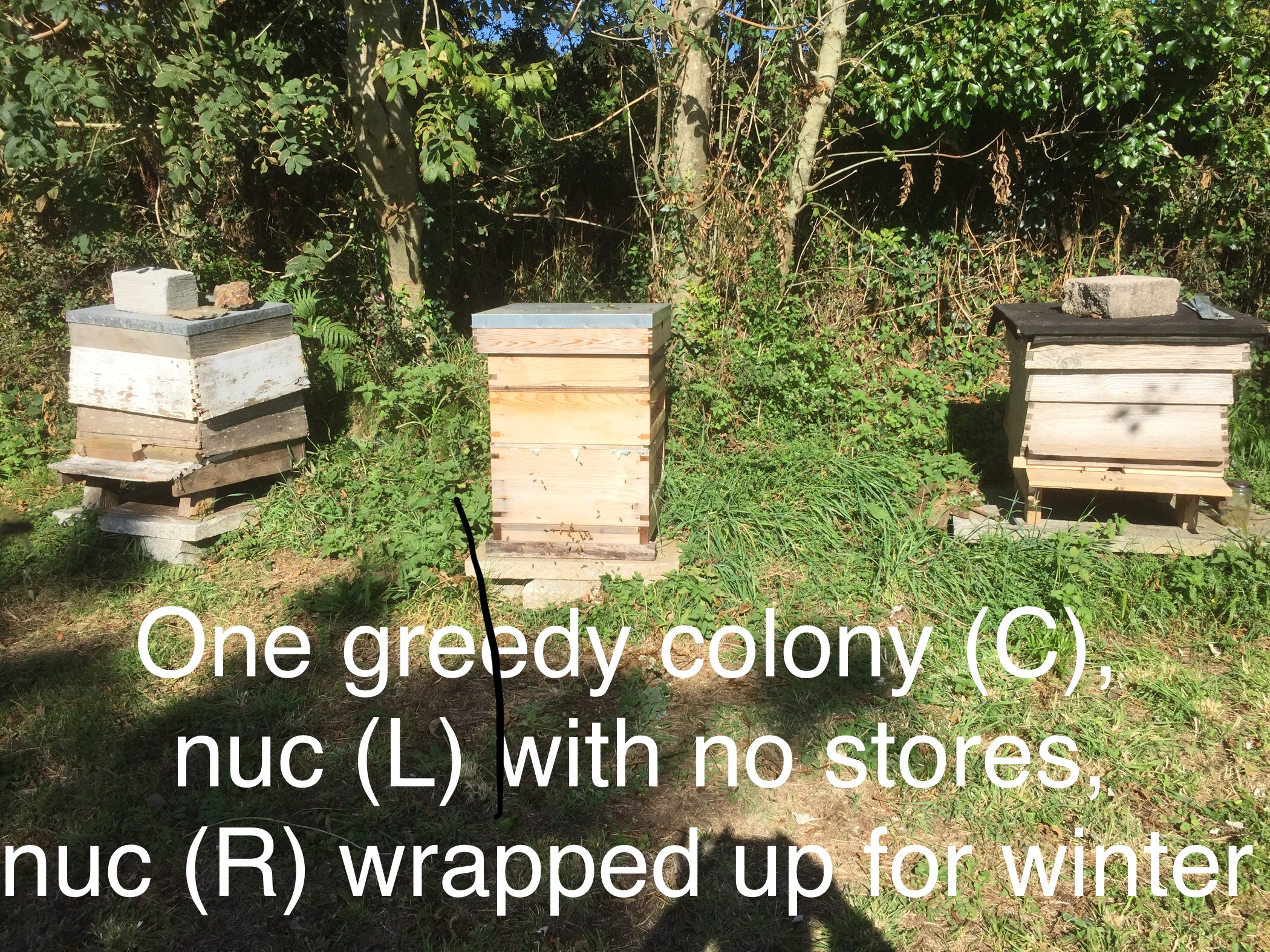

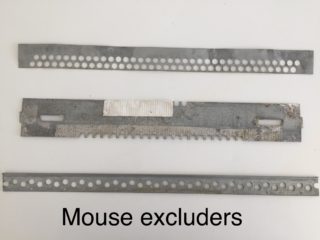

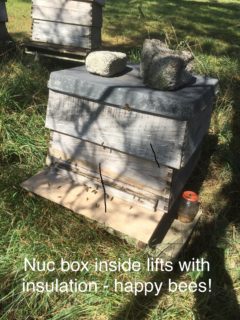

Just to illustrate the difference between bee colonies, even though they might have been established either as nuclei or swarms at the same kind of time, I have two other colonies worthy of mention. One is a queen-right nuc that I created from an established colony, which is still in its nuc box but working hard to be ready for winter. The other, again a nuc but one which I upgraded to a full brood box earlier on, is working so hard that they are building wild comb through the feeder hole in the crown board as they are so desperate for space!

When I spotted this I placed a queen excluder over the feed hole (rather than having to smoke them and remove the crown board to insert a queen excluder in its place) and placed an empty super on top. If they are in the nectar gathering, comb-drawing frame of mind then they will have all the space and materials they need to give me some surplus! So there you have two colonies established at about the same time, one content to contain themselves to a nuc box, the other roaring away into a full-sized brood box and wanting a super on top as well! That’s one of the fascinating things about beekeeping; no two seasons are the same, no two apiaries are the same, no two colonies in the same apiary are the same. It certainly keeps you on your toes!!

And talking of surplus, this is exactly what I need at the moment because, as I intimated last month, this year’s honey harvest has been dire. Barely half of what I obtained last year and all down to the weather (I’d say climate change but we all know that such a thing doesn’t exist because Trump says so!). So if I am lucky enough to get an ivy crop I’d be very pleased – as would my customers! There is some consolation in the fact that many beekeepers on the south coast of Cornwall have experienced the same. Ah well, there’s always next year!

Another example of how desperate the bees have been for forage, when I was checking my hives to see which had extractable honey and which didn’t, I came across one colony whose super frames were half-empty, as illustrated in one of my photographs last month.

I resolved to remove that honey ASAP but when I returned to the hive two days later, all the sealed honey had been removed and I was left with empty combs! The bees had taken it down into their brood chamber to save for winter stores! How ungrateful bees can be sometimes, and there’s me doing my best to look after them too! Anyway, they are now set up for the coming winter with stores from the summer and also the ivy to rely on.

Wasps have not been a major problem for me this year, though I know of others for whom they have been horrendous. I only ever saw the occasional opportunistic wasp looking to see what was easily available, so I wasn’t too worried about putting out wasp traps as my colonies were all very strong and could see off any occasional wasp nosing around their entrance – but I still put out a couple!.

However (there’s always a “however”, isn’t there?!), during one of my inspections, I took the roof off one hive and dozens of wasps flew out! Oh no! Were they were going to write off this particular colony as they have done to others in the past? The bees were flying strongly, and they had a small enough entrance that they could easily defend, so what was going on? All became clear once I removed the insulation sitting on top of the hive feeder.

At my previous visit, I had dislodged the cover to the feeder whilst replacing the insulation and the wasps had got a scent of that. There were about two dozen dead wasps floating in the syrup which otherwise was untouched by the bees – they obviously didn’t want the “pretend” feed when there was ivy available (good for them!) and the wasps were entering the hive between the inner hive boxes and the external lifts so they could fly straight up to the feeder on the crown board.

They weren’t going into the hive at all, just stealing the feed. I put the lid back on the feeder and carefully replaced the insulation. I then set up a jam jar wasp trap sitting on the crown board as an alternative to the pukka feeder and closed the hive up. Next time I checked, the wasps were still entering the carcass of the hive and flying up to the crown board but some had gone into the wasp trap.

One week later, no flying wasps! Phew! Such a relief to know my colony would not succumb to wasp predation, despite my error (which, of course, won’t happen again!).

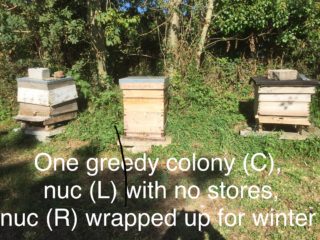

So, apart from putting mouse guards on the hives (no, not mice guarding the hives but rather perforated metal closers that fit across the hive entrance to allow bee passage in and out but prevent mice from getting in), my bees are just about ready to embrace whatever winter has in store for them.

Nucs are all insulated, many full-size brood boxes are insulated and have insulation on the crown board.

I just have to make fondant to place on all the hives to ensure the bees have enough food to see them through. Quite often the bees ignore the fondant as they are happy with their internal stores but it allows me to sleep at night knowing they have the option should they choose to take it. Then finally, any time between now and December, depending on the length of the ivy flow, I just have to remove the supers that might contain my ivy crop.

Will that be the end of the beekeeping year for me? Not by a long shot! There will be lifts and frames to repair, brood boxes, supers and frames to sterilise, and perhaps new equipment to make – so plenty to maintain one’s interest in the craft throughout the year. It’s not just about the honey!

Meanwhile, please continue to keep a look-out for Asian Hornets.

Meanwhile, please continue to keep a look-out for Asian Hornets.

Queens will be starting to search for winter quarters to hibernate shortly. If you see what you think might be one, let me know or use the Asian Hornet App to identify and photograph the sighting which can then be sent to alertnonnative@ceh.ac.uk All sightings so far in the UK have been made by members of the public so your role is extremely important and highly valued.

Colin Rees: 01872 501313 – 07939 971104 – colinbeeman@aol.com