Those in Peril on the Sea

Last month I wrote about wrecks, particularly those around our Cornish Coast. This set me wondering about rescue from these wrecks and, in particular, the part played by the R.N.L.I. This organisation was founded in 1824 in an unlikely place, a pub in Bishopsgate, London. Sir William Hillary, a gentleman officer in the Militia, witnessed a shipwreck rescue first hand.

Last month I wrote about wrecks, particularly those around our Cornish Coast. This set me wondering about rescue from these wrecks and, in particular, the part played by the R.N.L.I. This organisation was founded in 1824 in an unlikely place, a pub in Bishopsgate, London. Sir William Hillary, a gentleman officer in the Militia, witnessed a shipwreck rescue first hand.

This left such an impression that he wrote a pamphlet suggesting the formation of a body of men who would dedicate their lives to the rescue of shipwrecked mariners. He sent this to the Admiralty who ignored it. Undeterred he decided to appeal to the wealthy philanthropists of London and held a meeting in the London Tavern, Bishopsgate. They got King George IV on board and he consented to give his patronage to the new Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

The first RNLI boats were commissioned in 1825, scattered around the country which, then included what is now the Republic of Ireland. Purpose built lifeboats had existed since at least 1777 but they were operated on an ad hoc basis by the inhabitants of harbours around the country. So, even that far back, efforts were being made to rescue people from the then numerous wrecks that occurred around our shores.

I have never subscribed to the legend of Cornish wreckers and believe it to be a fable dreamed up by novelists to give spice to their stories. To me it is inconceivable that people who lived by the sea and, in many cases, made their living by it, should indulge in the practice of luring fellow seamen to their deaths. In any case the exhibiting of lights at night would normally be a warning to keep away, as they are today with the exception of red and green harbour entrances and marker buoys.

Bear in mind we are talking of wrecking large ships carrying cargo and passengers. There would be little profit in wrecking a forty foot fishing boat or a small ketch carrying several hundred clay pots! In the days of sail the masters of large vessels would not attempt to enter harbour in the dark, far too dangerous given the wind changes which can be happen as you close the land. The only ports on our coast capable of handling large vessels are Looe, Fowey, Falmouth, Penzance and possibly Padstow. All required a Pilot.

Bear in mind we are talking of wrecking large ships carrying cargo and passengers. There would be little profit in wrecking a forty foot fishing boat or a small ketch carrying several hundred clay pots! In the days of sail the masters of large vessels would not attempt to enter harbour in the dark, far too dangerous given the wind changes which can be happen as you close the land. The only ports on our coast capable of handling large vessels are Looe, Fowey, Falmouth, Penzance and possibly Padstow. All required a Pilot.

While you could sail into Falmouth in favourable conditions, the Black Rock in the middle has no light on it. The other four required assistance of a small rowing vessel to safely get inside. Unless there was an emergency Masters would wait for daylight before attempting an entrance. All that said I am the first to agree that, once a wreck had taken place, the populace for miles around would descend on the beach to salvage anything possible.

All the country’s lifeboats have interesting histories and a delve into the Cornish boats is no exception. There is an entry for the Fowey lifeboat which was originally at Polkerris, the station being built at the head of the beach in 1903. This entailed dragging the boat down the beach with horses. However as the First World War progressed the British Army’s need for horses had practically stripped the land and suitable beasts were unobtainable. The crew were supplied with long poles so they could push it down the beach to launch! In 1922 the boat was moved to Fowey where it could be kept afloat.

There used to be a boat at Portloe and it had the unique honour of never being launched to a rescue. It was stationed there in 1870 and the original house is now the Portloe Chapel. It was built side on to the road which made the heavy boat very difficult to manoeuvre to the slip. On one occasion it ran away and demolished a shop! They then built a new lifeboat house at the top of the beach alongside the present slip but it was always going to be a very tricky launch into a confined area of water. The boat was taken away in 1887 and the second lifeboat house became the village school.

There used to be a boat at Portloe and it had the unique honour of never being launched to a rescue. It was stationed there in 1870 and the original house is now the Portloe Chapel. It was built side on to the road which made the heavy boat very difficult to manoeuvre to the slip. On one occasion it ran away and demolished a shop! They then built a new lifeboat house at the top of the beach alongside the present slip but it was always going to be a very tricky launch into a confined area of water. The boat was taken away in 1887 and the second lifeboat house became the village school.

One of the most exposed Stations and the most southerly is Lizard. Like the Fowey boat it has been relocated several times mainly because of its inaccessibility and difficulty in making a successful launch. The first station was built above Polpeor Cove in 1859. Stand on Lizard Point with the main rocks stretching out below you and Polpeor Cove is to the west of the reef.

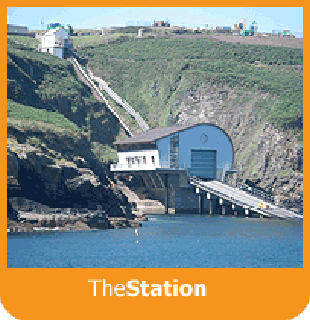

As such it faces west and is exposed to the full force of the prevailing gales. In 1866, while on exercise in bad weather, the boat was thrown back onto the rocks and three men lost their lives. Following this the place was abandoned and a new boathouse built at Church Cove on the east side of the point, where itl remains today, though it is now on its third or fourth boathouse.

As such it faces west and is exposed to the full force of the prevailing gales. In 1866, while on exercise in bad weather, the boat was thrown back onto the rocks and three men lost their lives. Following this the place was abandoned and a new boathouse built at Church Cove on the east side of the point, where itl remains today, though it is now on its third or fourth boathouse.

The earliest lifeboat in Cornwall is Penzance, financed by Lloyds of London. It was sold in 1812 having never been used and was not replaced until 1826 with the formation of the RNLI. It was again stationed at Penzance. There appears to have been much haggling and argument between the citizens of Penzance and Newlyn about the honour of having the lifeboat and it moved about between the towns until 1913 when a new lifeboat house was built at Penlee Point.

Boats were then involved in several heroic rescues, one of the most notable being the rescue of eight men from the hulk of HMS Warspite, under tow to be broken up. Warspite was an iconic battleship from the First and Second World Wars, having served in practically every theatre of war at sea. Having reached the end of her life in 1947 she was under tow to Faslane in Scotland to be broken up when she broke adrift off Mounts Bay.

She was blown ashore at Prussia Cove. There she stayed until another salvage attempt in 1950 which again failed. She ended up off St Michaels Mount. As an interesting aside she was eventually broken up as salvage by a firm created by two Scotsmen, both of whose names began with ‘Mac’. They called their new firm Macsalvors!

In 1960 the Penlee Station took delivery of the 47ft Watson Class boat ‘Solomon Browne’. You now all know the story so I won’t go into it again except to say that, following the disaster, the RNLI re-located to Newlyn where the boat can remain afloat.

The most westerly mainland station in Cornwall is Sennen Cove which, like Penzance, pre-dates the formation of RNLI, the first lifeboat being stationed there in 1803. In 1868 the crew participated in a unique rescue when they went to the rescue of the crew of the lighter ‘Devon’. By the time they arrived there was only one survivor left on board but as the vessel was well on the rocks the lifeboat could not reach him.

The most westerly mainland station in Cornwall is Sennen Cove which, like Penzance, pre-dates the formation of RNLI, the first lifeboat being stationed there in 1803. In 1868 the crew participated in a unique rescue when they went to the rescue of the crew of the lighter ‘Devon’. By the time they arrived there was only one survivor left on board but as the vessel was well on the rocks the lifeboat could not reach him.

They got him off by using a breeches buoy, a system never designed for use on a vessel, involving a rocket being fired carrying a line to the casualty. This could not have been a spontaneous idea but would have needed prior preparation so, obviously, an inventive coxswain was using his initiative!

St Ives boat has an interesting history. In February 1873 two schooners and a brig were driven ashore and the St Ives rowing boat was launched. Thirteen men were rescued but the lifeboat had to change its exhausted crew five times in order to do so. In 1939 tragedy struck. In a severe gale the boat was launched to go to the aid of an unknown vessel.

The lifeboat capsized and four of her crew were lost. A self righting boat she capsized again and one more man was lost. She went over again, two more were lost and then she was thrown onto the rocks of Godrevy. One single crewman survived and scrambled ashore.

Our north coast has a sad history of RNLI casualties, none more so than Padstow. It began in 1826 when four pilots went to try and save the crew of a stranded brig. Their rowing boat capsized and three were drowned. This incident brought about the formation of a local branch of the infant RNLI. In February 1867, on service to a rescue on the Doom Bar, the rowing lifeboat capsized and five of her crew of 13 were drowned.

Then, in August 1879, a most unusual event occurred. Five young ladies, four from the same family, were being towed back into the harbour behind a fishing boat being handled by the lifeboats assistant coxswain. This would seem to have been just a casual courtesy tow. They then saw another boat capsized in a squall, three men being thrown into the water. The ladies immediately asked the coxswain to cast off the tow so they could go to the rescue.

At first he demurred but they were persistent and he eventually did. The ladies, in bad conditions, rowed over to the scene and were able to rescue one man, though two drowned. The ladies were awarded the RNLI’s silver medal, unusual but not unknown for it to be awarded to a ‘civilian’.

In April 1900 the pulling boat was launched to assist a ketch on the rocks. At the scene she was hit by a tremendous wave which broke ten of her oars and pitched the crew into the water. They were able to get back into the boat but she was thrown onto the rocks, becoming a total loss. At this point the Padstow steam lifeboat was launched to go to their rescue but, as she was leaving harbour, she was hit by a heavy swell and capsized. Eight of her eleven crew were lost.

There are so many incidents recorded about our Cornish lifeboats that it has not been possible to visit them all so I apologise for omissions. We are fortunate that, in this country, we have such an efficient system of rescue for those caught out in our local waters or walking the cliff path. It involves highly skilled professionals and well trained volunteers, who now accept one another as being part of the overall rescue picture.

There are so many incidents recorded about our Cornish lifeboats that it has not been possible to visit them all so I apologise for omissions. We are fortunate that, in this country, we have such an efficient system of rescue for those caught out in our local waters or walking the cliff path. It involves highly skilled professionals and well trained volunteers, who now accept one another as being part of the overall rescue picture.

Whether you are a professional coastguard or a volunteer for cliff rescue, a paramedic dangling from a helicopter or a trained Coastwatch volunteer, we all realise that we are part of a great organisation whose object is to rescue those in need. The young and fit do their part as RNLI beach guards. Ladies and gentlemen of the NCI may be more mature. No one will expect us to jump from a heaving lifeboat on to a wallowing yacht but we play our part. This is an organisation you can join. Give Sue a ring on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681

Pictures courtesy of RNLI and Wikipedia