There Is A Reason For Everything

There Is A Reason For Everything

Our last training exercise involved the identification by photograph of the rigs of sailing vessels, which we see from our Lookout. These were mainly yachts but among them were a few shots of or local working boats. Actually I should not use the term ‘working boats’ as none of them are now working but are all lovingly preserved by individuals and syndicates. The only boats now working under sail in Falmouth are the few oyster dredgers, which gather the oysters from the harbour bed and have to work under sail in order to get their licence. This is in order to preserve the beds from the predatory activities of modern methods.

Even more so it is wrong to use the term ‘Falmouth working boats’. A better description would be ‘West Country working boats’ as in the days of sail there would be many different types and boats which were selected for use in various ports because of their suitability for the required task. There were luggers, trawlers, pilchard drifters, crabbers, hookers, salmon boats, toshers, punts, picarooners, – the list goes on. The lugger, for example, was a very common sail plan and might be built in Looe but work out of Mevagissy. Picarooners were beach boats about 16ft long and designed to be kept on a stony beach. They were built almost flat-bottomed for stability so two men could stand up and haul a net. Being small and light two men could easily haul one down the beach to the sea when the silver darlings were seen off the coast. Just like the pilchard shoals men would watch for them and then there would be a rush to get boats in the water. When they reached the end of their working life they would be painted green to signify they were not to be used and then left on the beach.

Then there were cargo carriers – trows from Bristol, barges, schooners, brigs and a variety of specialists like Bristol Channel pilot cutters, tenders, flatners. The point was that vessels were designed and rigged to do specialist jobs. Some were fast, some were flat bottomed to sit on the ground, some had very deep keels, some were luggers, some sprit sails – everything had a purpose. They had design points to meet various needs. Those massive long bowsprits we see on some local boats were there to increase sail area and to get it as far forward as possible. Combine that with a very deep keel and you had a boat, which could be relied upon to behave itself when crew were handling nets. But that same bowsprit was a liability in harbour. Imagine forty odd boats all crowded into a small harbour, each with a sixteen-foot long prodder sticking out! So they are designed to be run-in when in harbour. Thames barges, huge vessels with a massive mainsail and a small topsail very high up, had only a crew of two. But the topsail could stick up above surrounding fields to allow the boat to sail a long way up rivers. Sailboat designs have evolved as the special needs demanded.

Then there were cargo carriers – trows from Bristol, barges, schooners, brigs and a variety of specialists like Bristol Channel pilot cutters, tenders, flatners. The point was that vessels were designed and rigged to do specialist jobs. Some were fast, some were flat bottomed to sit on the ground, some had very deep keels, some were luggers, some sprit sails – everything had a purpose. They had design points to meet various needs. Those massive long bowsprits we see on some local boats were there to increase sail area and to get it as far forward as possible. Combine that with a very deep keel and you had a boat, which could be relied upon to behave itself when crew were handling nets. But that same bowsprit was a liability in harbour. Imagine forty odd boats all crowded into a small harbour, each with a sixteen-foot long prodder sticking out! So they are designed to be run-in when in harbour. Thames barges, huge vessels with a massive mainsail and a small topsail very high up, had only a crew of two. But the topsail could stick up above surrounding fields to allow the boat to sail a long way up rivers. Sailboat designs have evolved as the special needs demanded.

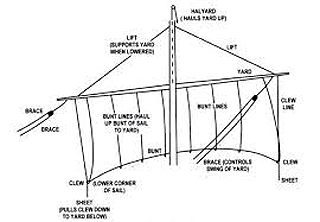

Boat sails can be divided into two classes – square sails and fore and aft sails. Square sails are carried on heavy poles or yards, which run across the ship attached to the masts. The sails drop down from the yards just like a window blind and, like a blind, they can be rolled up or gathered in and tied in place when not required. Fore and aft sails are hoisted, on ropes or halliards, secured at the bottom with more ropes called sheets. These sails are just simply dropped when not required. But the sails could not perform their purpose without the other essential element – the keel of the boat. If the boat were simply flat bottomed then the wind would always drive it in the direction the wind was blowing. So the hull is carried down below the waterline to give resistance to the force of the wind. You get the wind trying to push the boat one way and the keel trying to stop it going. This is the ‘orange pip effect’. What happens is exactly like when you try and squeeze an orange pip between thumb and forefinger – it flies off into the blue! There is a whole science in this, an essential part of the yacht designers’ skill. Without getting too complicated a point is calculated on the whole sail plan, which is centre to the ‘pushing effect’. This is called the ‘centre of effort’. The point of the keel, which concentrates the resistance against the push is called the ‘centre of lateral resistance’. The yacht designer has to calculate these and ensure that they are in correct relationship with one another. Get it right and the ship goes forwards. Get it wrong and she may go backwards!

Even the wood of which a wooden ship was made is important. In general wood does not like prolonged immersion in water and in seawater there are all sorts of nasty wriggly things that will eat wet wood. Teredo worm, also called shipworm, and gribble are the general terms for these. They are not really worms at all. Teredo is an elongated mollusc and gribble is an isopod but to the seaman they are both a menace, which, if there is no protection, will destroy a vessel by eating its timber to a hollow shell. Teredo, a tropical creature, is normally about three feet long but a five foot specimen has recently been found. Gribble is an inhabitant of temperate climes and about the size of a big woodlouse. The protection to keep these at bay is to sheath the hull in copper (expensive) or paint it with anti-fouling paint which is the colourful patch seen below the water line of a yacht as the wind heels her over.

Even the wood of which a wooden ship was made is important. In general wood does not like prolonged immersion in water and in seawater there are all sorts of nasty wriggly things that will eat wet wood. Teredo worm, also called shipworm, and gribble are the general terms for these. They are not really worms at all. Teredo is an elongated mollusc and gribble is an isopod but to the seaman they are both a menace, which, if there is no protection, will destroy a vessel by eating its timber to a hollow shell. Teredo, a tropical creature, is normally about three feet long but a five foot specimen has recently been found. Gribble is an inhabitant of temperate climes and about the size of a big woodlouse. The protection to keep these at bay is to sheath the hull in copper (expensive) or paint it with anti-fouling paint which is the colourful patch seen below the water line of a yacht as the wind heels her over.

Woods are hardwoods or softwoods. Hardwood as the name implies is strong and long lasting, the penalty being weight. Softwood is light, and easy to work, but the penalty is a short life at sea. These are generally pines but there is one pine, which flouts this rule. Pitch pine is a native of New England, is very resinous and this makes it long lasting and fairly light. Shipworms don’t like the taste of the resin so it is good in salt water. English warships were usually made of oak and held together with wooden pegs making a solid, stable gun platform. The French used a lot of pine and held it together with iron nails. Nails rust – nail sickness in marine terms. This showed up at Trafalgar where English ships absorbed immense punishment without serious harm while French ships were badly damaged. The downside of oak under cannon fire is that it splinters and more English sailors were killed by flying wood splinters than by enemy gunfire! A cannonball passing through a hull would send spears of wood – often six or seven feet long – flying about the crowded decks.

Woods are hardwoods or softwoods. Hardwood as the name implies is strong and long lasting, the penalty being weight. Softwood is light, and easy to work, but the penalty is a short life at sea. These are generally pines but there is one pine, which flouts this rule. Pitch pine is a native of New England, is very resinous and this makes it long lasting and fairly light. Shipworms don’t like the taste of the resin so it is good in salt water. English warships were usually made of oak and held together with wooden pegs making a solid, stable gun platform. The French used a lot of pine and held it together with iron nails. Nails rust – nail sickness in marine terms. This showed up at Trafalgar where English ships absorbed immense punishment without serious harm while French ships were badly damaged. The downside of oak under cannon fire is that it splinters and more English sailors were killed by flying wood splinters than by enemy gunfire! A cannonball passing through a hull would send spears of wood – often six or seven feet long – flying about the crowded decks.

We made our large cargo vessels of oak as well but the Americans chose pine. I suppose they had large quantities of it. This meant that their vessels were fast because they were lighter. If you research the clipper ships you will come up with a dozen different speed records. The trouble is that there is no set criteria – was it greatest distance in 24 hours, the fastest port to port crossing or the greatest recorded speed for a short time. We must accept that most of the record holders were American. The penalty they paid was that they had a short life as the wood rotted. The most famous episode of all was the Tea Race back from Shanghai in 1872 between English ships Cutty Sark and Thermopylae. They left Shanghai at the same time and raced neck and neck for seven weeks until the Cutty Sark lost her rudder off the coast of South Africa. She had to put in for repairs and Thermopylae was first into London but Cutty Sark, despite her troubles, was only nine days after her.

There is one conclusion from all this. With safety at sea there are no short cuts. Everything is done for a reason. Good quality will keep you safe – but only if you act sensibly. This is very true of what I call ‘the leisure industry of the water’. This is the dinghies, kayaks, paddleboards, and swimmers etc who go into the sea around our Lookout. Lifejackets are necessary; wet suits will keep you warm. Stay within your depth if you cannot swim. Try to ensure that someone on land knows you are going in the water. Above all – if you are using an outboard motor make sure you have enough fuel! Really it is down to common sense but you must accept that you have to play your part and think about what might happen. Then, if it does happen, the Watchkeepers on Pednvadan will play their part and get help to you as quickly as possible. Let’s hope you did wear that life jacket and are still above water!

There is one conclusion from all this. With safety at sea there are no short cuts. Everything is done for a reason. Good quality will keep you safe – but only if you act sensibly. This is very true of what I call ‘the leisure industry of the water’. This is the dinghies, kayaks, paddleboards, and swimmers etc who go into the sea around our Lookout. Lifejackets are necessary; wet suits will keep you warm. Stay within your depth if you cannot swim. Try to ensure that someone on land knows you are going in the water. Above all – if you are using an outboard motor make sure you have enough fuel! Really it is down to common sense but you must accept that you have to play your part and think about what might happen. Then, if it does happen, the Watchkeepers on Pednvadan will play their part and get help to you as quickly as possible. Let’s hope you did wear that life jacket and are still above water!

We must prepare as well and, unfortunately, are not there yet. We do not have enough volunteers to cover our Watches every day of the week. Numbers are creeping up but we still want more. Find out how you can help – give Sue a ring on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01726-270681.

Oh! ‘Silver darlings’ are herrings or pilchards depending on which part of the country you are in.

Pictures courtesy Wikepedia and own stock