What About Pluto Then?

When man first started travelling abroad he had great difficulty in contacting the family back home or the boss to get instructions. There was no e-mail, no telephone, no electricity no nothing. Yet there was still need for Governments to contact their representatives, businesses their staff and families their loved ones. The only means was by letter sent by ship – a slow and uncertain business. King George, wishing to chase up local officials, would have to wait at least six weeks to get a reply. Victoria, seeking news of the Indian Mutiny, would hear nothing for even longer. There was no Suez Canal so ships went round Cape of Good Hope, a journey which could take months.

When man first started travelling abroad he had great difficulty in contacting the family back home or the boss to get instructions. There was no e-mail, no telephone, no electricity no nothing. Yet there was still need for Governments to contact their representatives, businesses their staff and families their loved ones. The only means was by letter sent by ship – a slow and uncertain business. King George, wishing to chase up local officials, would have to wait at least six weeks to get a reply. Victoria, seeking news of the Indian Mutiny, would hear nothing for even longer. There was no Suez Canal so ships went round Cape of Good Hope, a journey which could take months.

Much depended upon the speed of the ship concerned. A fast ship, lightly built for speed, was obviously capable of knocking days or weeks off the travel time. In 1688 Falmouth was appointed as the official Royal Mail Packet Station and the harbour was full of ships engaged in this trade. They were designed to only carry a small amount of cargo and a few passengers who could pay the premium for a fast passage. They were lightly armed, intended to evade conflict by speed rather than seek it and the service proved a great success. All went well until 1823 when the Government interfered (isn’t that what Governments do?).

The wars with France and America were over and the Government had a large surplus of warships. Casting their eyes about for some ways to save or make money the Government took over the Packet Service from the Post Office and, instead of using the light and fast Packet ships, used redundant warships. These were slower, heavier, older and more battered from war service. There was no advantage of speed for passengers or commerce. The steamship had been invented and rapidly became faster and more reliable. The Post Office started sending post by these vessels and the Falmouth Packets became history.

The wars with France and America were over and the Government had a large surplus of warships. Casting their eyes about for some ways to save or make money the Government took over the Packet Service from the Post Office and, instead of using the light and fast Packet ships, used redundant warships. These were slower, heavier, older and more battered from war service. There was no advantage of speed for passengers or commerce. The steamship had been invented and rapidly became faster and more reliable. The Post Office started sending post by these vessels and the Falmouth Packets became history.

In 1839 the first working telephone was made using overhead copper cables and the idea took root that it might be possible to run a cable underwater and reduce distances. In 1842 our friend Samuel Morse experimented successfully with a cable running under New York harbour and later a Charles Wheatstone ran a cable under water in Swansea Bay. The biggest problem was how to make a cable waterproof yet retain a degree of flexibility. The unlikely answer to this came from the medical profession. William Montgomerie, a surgeon with the East India Company, had seen a gum from a tree which was both waterproof and flexible. This was called gutta-percha.

He had seen whips made out of this in India and wondered if it could be used in the medical field as a surgical stitch. Later Michael Faraday and Wheatstone successfully used it to coat a copper cable. They already had the idea of a cable across the English Channel and in 1850 the first submarine cable, wire simply coated with gutta percha, was laid between England and France. It was not a success – the coating alone did not remain waterproof but the idea was there. They tried again with a rubberized cable and gutta percha and that worked. The submarine cable was born.

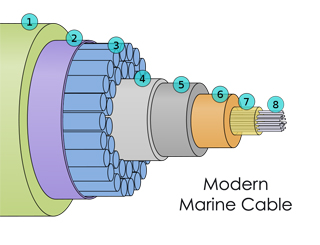

Now days the submarine cable is a complex thing, far removed from the somewhat simple idea of a waterproofed copper wire which began the saga. To start with it was simply a copper wire, a rubber sheath and gutta percha. They found that this was not strong enough to survive the underwater environment, the stress of laying it, and the battle against tide and underwater currents. So it got bigger and more robust but this brought the penalty of weight. The distance from UK to America is over 4,000 miles. The ideal was that a single ship would be able to carry enough cable to cover this distance but this proved impossible.

Now days the submarine cable is a complex thing, far removed from the somewhat simple idea of a waterproofed copper wire which began the saga. To start with it was simply a copper wire, a rubber sheath and gutta percha. They found that this was not strong enough to survive the underwater environment, the stress of laying it, and the battle against tide and underwater currents. So it got bigger and more robust but this brought the penalty of weight. The distance from UK to America is over 4,000 miles. The ideal was that a single ship would be able to carry enough cable to cover this distance but this proved impossible.

The most cable the ‘Great Eastern’ could carry would only cover 2500 nautical miles. This weighed 7500 tons! Then, as technology progressed, the cable got bigger and heavier so the amount that could be carried was reduced. Since the end of the War there have been giant steps in this type of work. The modern cable is a composite of about eight different materials and only about one inch thick. Fibre optics are used thus improving signal quality as well as reducing weight. The fact remains though that the undersea cable is the most secure communication method yet devised as nothing passes into the realm of the internet or space communication.

Our ‘local’ interest is, of course, that the first Trans-Atlantic cable came ashore at Porthcurno, a few miles this side of Lands End. It was laid by the ‘Great Eastern’, then the world’s largest steam ship. As a passenger carrier she proved something of a white elephant but converted to a cable layer she was an outstanding success, later going on to lay the first cable between UK and India. We now had a means of telephonic communication between countries and the political and commercial world changed. Instructions were instantaneous, replies immediate. True they began by using Morse code but this soon graduated to speech and, of course, later digital. Even today the majority of intercontinental transmissions are by cable on grounds of cost and security. You are not firing your secrets into the ether for any Tom Dick or Harry to read. The cable itself is secure, short of someone picking it up and breaking into it. Secrecy becomes a problem at either end if, having sent the message by cable to the country concerned, it is then forwarded to its destination by satellite.

Our ‘local’ interest is, of course, that the first Trans-Atlantic cable came ashore at Porthcurno, a few miles this side of Lands End. It was laid by the ‘Great Eastern’, then the world’s largest steam ship. As a passenger carrier she proved something of a white elephant but converted to a cable layer she was an outstanding success, later going on to lay the first cable between UK and India. We now had a means of telephonic communication between countries and the political and commercial world changed. Instructions were instantaneous, replies immediate. True they began by using Morse code but this soon graduated to speech and, of course, later digital. Even today the majority of intercontinental transmissions are by cable on grounds of cost and security. You are not firing your secrets into the ether for any Tom Dick or Harry to read. The cable itself is secure, short of someone picking it up and breaking into it. Secrecy becomes a problem at either end if, having sent the message by cable to the country concerned, it is then forwarded to its destination by satellite.

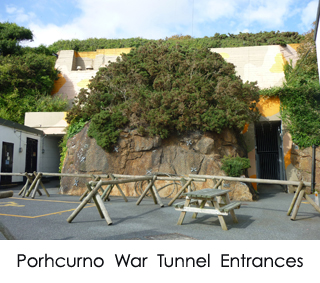

The Museum at Porthcurno is fascinating. Apart from setting out the history of undersea cable it tells the story of the vital part this complex played in the Second World War. Communication with the rest of the world, particularly America, was crucial. Yet this site was only about 100 miles from Brest, the French port now occupied by the Germans, capable of mounting a serious land/sea operation. To guard against this it was decided to move the whole complex underground. To start with Cornish mining expertise was used to drill two main tunnels in to the rock, then these were connected by cross tunnels. The tunnels were protected by double bomb proof and gas proof doors. Then the whole set up was moved inside the rock from where it operated throughout the War. All the conversations between Churchill and Roosevelt, the overall command of armies throughout the world and the political conversations necessary between us and our Allies passed through here.

The Museum at Porthcurno is fascinating. Apart from setting out the history of undersea cable it tells the story of the vital part this complex played in the Second World War. Communication with the rest of the world, particularly America, was crucial. Yet this site was only about 100 miles from Brest, the French port now occupied by the Germans, capable of mounting a serious land/sea operation. To guard against this it was decided to move the whole complex underground. To start with Cornish mining expertise was used to drill two main tunnels in to the rock, then these were connected by cross tunnels. The tunnels were protected by double bomb proof and gas proof doors. Then the whole set up was moved inside the rock from where it operated throughout the War. All the conversations between Churchill and Roosevelt, the overall command of armies throughout the world and the political conversations necessary between us and our Allies passed through here.

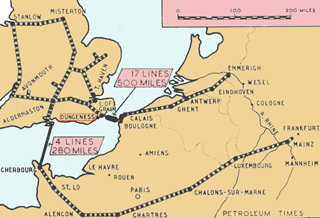

Now back to PLUTO. No, not Mickey Mouse or even the Planet. Spread the letters out. Pipe Line Under The Ocean. This was one of the many whacky ideas that made up the successful invasion of France that would bring the Second World War to an end. This idea was two flexible pipelines, one running from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg the other Dungeness to Calais, laid on the sea bed, that would carry petroleum across after the invasion to keep the Army and Air Force supplied. Tankers could be held up by weather or sunk by U-Boats but a pipeline could give continual if more reduced supply. Many thought it could not be done but trials were made, first in Scotland and then in the Bristol Channel and, as a result, Operation Pluto received official blessing. It was decided that multiple pipes would be laid at each site to maximise flow and guard against damage interrupting the supply. About 500 miles of pipe would be needed!

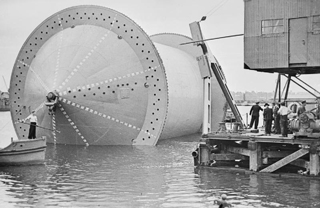

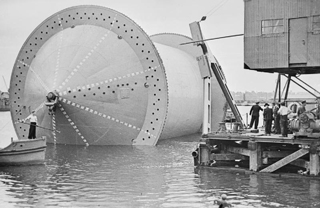

Two methods of holding and laying the pipe were tried. One was a vertical drum mounted internally in a ship, the pipe being fed out over the stern as the ship went ahead. The other was a giant cotton reel lying on its side, built in to a dedicated barge, which was then towed behind tugs. Two types of cable were produced, one lead based and one steel based. Each drum was capable of holding 40 – 50 miles of cable so a technique had to be developed to make joins at sea. The weight of the pipe on each drum would be up to 4,000 tons – heavier than the combined weight of two destroyers! To prevent them being crushed by their own weight while on the drum they were filled with water under pressure.

When first laid in January 1945 the pipes only handled a disappointing 500 tons of fuel per hour. By the end of March this had increased to 4,000 tons per hour – over 1,000,000 per day! The ‘whacky idea’ kept the drive by the Armed Forces going and without it Germany’s defeat would have taken much longer and cost more lives. You can read about it in more detail on the Web under ‘Combined Operations – PLUTO’ to which website I am indebted.

I started this article a couple of days before I did two watches at the Lookout in wonderful weather. As I looked out at a benign sea I found it difficult to imagine the trials and tribulations of those men and women directly involved in projects like these, first thought of in 1942 and coming to fruition in 1945 – all the disappointments, discomfort from the weather, separation from families, the drive and leadership needed to bring it to a successful conclusion. Are we not lucky today? There was I on a beautiful day, doing a worthwhile job, surrounded by reliable electronic equipment, the full help of H.M. Coastguard just a telephone call away, certain that the systems would work if the Lifeboat or Rescue Helicopter were needed. But we could still do with a few more people. Ring Sue on 01872-530500 or Chris on 01326-270681.

Pictures courtesy of Wikipedia.